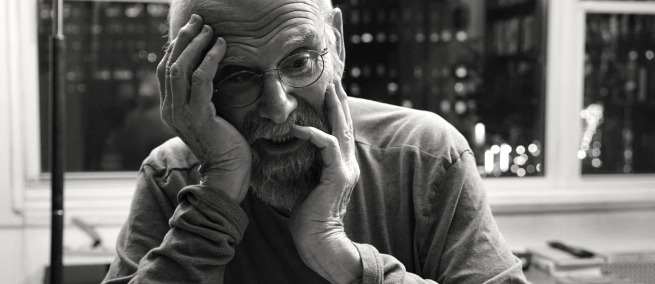

OLIVER SACKS: HIS OWN LIFE is a new documentary about the beloved author and neurologist Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat). Directed by Ric Burns, the film tells the story of how Sacks came into his own in his work—an outsider who ultimately influenced a generation of scientists—and also how Sacks lived the end of his life; Burns and his team started filming in 2015, when Sacks had just received a mortal cancer diagnosis. The film premiered at the 2019 Telluride Film Festival followed by the New York Film Festival, and is opening nationwide on the virtual cinema platform Kino Marquee and Film Forum virtual cinema starting September 23.

We first spoke with Ric Burns in 2018 when he was in the midst of making the film and had received support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. We followed up with him at the end of August to discuss the final film. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Science & Film: How is this film different than your other work?

Ric Burns: We decided there wouldn’t be narration, and also that it was going to be able to speak in a different way from the films I’d worked on. We had to be both open and determined to capture our subject, to do it all in his words and those of the people who had known him, but also to find the story that was in this material, alert to all the many layers.

S&F: What comes out of the film as one of Oliver Sacks’s biggest contributions is the way that he put himself into his work. Through the process of observation, care, and writing he was able to make a distinctive contribution to the science of human behavior as well as to our understanding of consciousness. Does that ring true?

RB: One hundred percent. You’ve seized on something so central to Oliver which is that the scientific quest, the writerly quest, and the biographical quest are all merged. He was deeply obsessed with reality at every level. He was not a behaviorist, though behavior was crucial to him; he wanted to know, who is behaving like that? And thank god he did that, because while everybody else was trying to figure out the observable, measurable parts of behavior—from B.F. Skinner onwards—he was saying, the experience itself is data. People went, sorry, that’s not data. I can’t turn that into a repeatable experiment, it’s not measurable. Oliver felt, you know what, it is. We can get a hold of it. It’s going to take time, and an enormous utilization of the very instrument we’re studying: a conscious being is going to have to sit down with other forms of consciousness and spend a lot of time accumulating biographical data and biological data, then collate from the biographical to the biological and back. Then, he’s going to do the only thing you can do to “measure” it: He’s going to turn it into words. He’s gotta say, hey, the man who mistook his wife for a hat, do you recognize yourself in this? So it’s a back and forth process with the experiencer.

Oliver is a doctor, a writer, a scientist, an artist, he is all of those things! He shows that those are false distinctions. Art is the science of human subjectivity.

S&F: I imagine it was challenging to balance what in the film you wanted in Oliver’s own words versus what we hear from others who knew him. How did you make those decisions?

RB: We spent almost all of our energy with Oliver first. We shot 90 hours five days a week—February 9, 2015 until February 13, 2015, always with his group of people, [including] his late-in-life partner Billy Hayes, his chief of staff for 35 years Kate Edgar, and family members. Almost everybody else we interviewed after Oliver died, starting pretty much right away. Trust was key. The trust was built in, for which I am so moved and so profoundly humbled, and we were going to honor that of course, like anybody would. [The film is] two stories: one begins in 1933, the second story is the story of, I got a mortal diagnosis and I’ll be dead in six months.

S&F: It must have been an intense filming process.

RB: It was so intense. I have to say, one’s obsessed with any project you work on, this one has been the… the sense of having a living, beating thing under your care, there’s a kind of pastoral duty—we’re like undertakers, we have to help in that process of getting him into the ground. It was challenging to do that.

Two weeks before he died, Oliver went to a lemur colony in North Carolina. There’s a picture of him holding a lemur in the film and there he is doing what he’s always done, going, that’s incredible, there’s somebody in there. That is the central Oliver activity: who are you? How can I understand you? How can I articulate it to myself, how can I create something I can share between us? That’s going to be partly art, partly science, partly words, partly neurology. Ultimately, all those are part of the same thing.

♦

OLIVER SACKS: HIS OWN LIFE will be available online beginning September 23. Directed by Ric Burns, the film is produced by Leigh Howell, Bonnie Lafave, and Kathryn Clinarad. It features friends and colleagues of Oliver Sacks including Temple Grandin, Christof Koch, Robert Krulwich, Lawrence Weschler, Bill Hayes, Atul Gawande, and Kate Edgar.

TOPICS