After the 2018 Sundance Film Festival–where Aneesh Chaganty’s feature debut SEARCH won the Sloan Feature Film Prize–Science & Film sat down with the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation’s Vice President of Programs Doron Weber. Weber directs the Foundation’s Public Understanding program, supporting film, theater, radio, television, books, and new media projects which integrate scientific or technological themes or characters. He has been supporting such film projects at the Foundation since 1997, and has made grants integral to the success of films including HIDDEN FIGURES, PRIMER, and THE IMITATION GAME.

Science & Film: Over the past year, the Foundation has supported a number of stories featuring women in science including HIDDEN FIGURES. Has the Foundation shifted to supporting these stories because of the Me Too movement?

Doron Weber: We are doing the same thing we always have done, it’s just that we’re more in sync with the culture. Now people seem more ready to hear these stories of amazing women in general, and women in science specifically. I think the big difference also is people understand you have to put more women in positions where they can make decisions about these films. So that’s promising too.

We’re very happy with the documentary BOMBSHELL: THE HEDY LAMARR STORY [by Alexandra Dean] because that is the longest commitment we have had to telling any woman in science story. It started 17 years ago, with a small grant to Ensemble Studio Theatre for a play about Hedy Lamarr, FREQUENCY HOPPING [by Elyse Singer], which took eight years to be produced. In 2004, we made a grant via the Tribeca Film Institute for a screenplay about Lamarr that we worked on for several years but ran into a dead end. So then we commissioned a book by Richard Rhodes, Hedy’s Folly, that was published to acclaim [in 2011]. That book was optioned by the actress Diane Kruger and we made a grant to help her adapt Hedy’s Folly into a series. While working on that, we made a major grant in 2015 to Susan Sarandon’s company Reframed Pictures for a documentary about Lamarr called BOMBSHELL which premiered at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival. It opened in theaters in November. It made a couple of Top 10 lists and it’s going to be broadcast on PBS’ American Masters in May. We’re continuing to work with Diane Kruger, and now Google and Straight Up Films have joined us to develop a miniseries. Diane won Best Actress at Cannes in 2017 for a film, IN THE FADE. So in terms of the public knowing Hedy Lamarr’s story, we feel we have made progress.

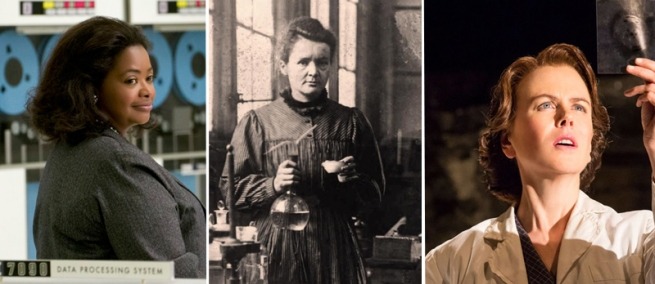

Regarding other women in science stories, Nicole Kidman played Rosalind Franklin in the West End production of the Sloan-supported play PHOTOGRAPH 51 by Anna Ziegler, and we’re hoping that will come to Broadway and then be made into a film with Kidman or another great actress. We have two Marie Curie projects in the works, A Noble Affair and RADIANT by two Australian filmmakers, which is moving forward. RADIUM GIRLS [by Ginny Mohler and Lydia Pilcher] has been completed and will debut in the first half of this year.

S&F: Was the Radium Girls story one that you had heard before you read Ginny Mohler’s script?

DW: I was aware of it but we’d never had such a strong screenplay. It’s a notorious story about young women in the United States Radium factory innocently painting watch dials with radium paint, licking paintbrushes and getting necrosis of the jaw and bone fractures from radiation poisoning. The company covered up the truth this truth. It’s unbelievable. Of course radium also has positive uses, such as treatment for cancer, but here it was grotesquely abused. I’ve seen early cuts of the film and I think it has some remarkable performances.

Also, HIDDEN FIGURES is not over. There is supposed to be a television series that National Geographic is producing. And I’m talking to the film’s producer Donna Gigliotti and author Margot Lee Shetterly about other possible media for that story.

S&F: What do you think is the impact of the success of HIDDEN FIGURES?

DW: The title Hidden Figures has already become a household term. What the book and the movie showed us is that hiding in plain sight are these amazing stories; not just one, not two, not three, but dozens, possibly hundreds of these African American women scientists, engineers, and mathematicians who played a role in the space program at NASA and no one knew about them or their contributions. So the question is, how many other stories like this are out there that we have been blind to? It tells us about our unconscious bias or our cognitive blind spots. There is both overt discrimination and unconscious bias preventing women and underrepresented minorities from entering STEM fields, but even when they succeed in having a STEM career and making a contribution, even when they do extraordinary things, we are not paying adequate attention and recognizing them.

The other thing I think HIDDEN FIGURES has going for it is that it is non-partisan. Both the left and right can embrace it. Liberals love the focus on equality and social justice, and conservatives love its patriotism and rugged individualism. Barack and Michelle Obama and then Ivanka Trump all hosted HIDDEN FIGURES screenings at the White House! It’s a reminder that we need to find stories that unite us and show what we have in common. And that we may have to look a little harder, or use a different lens. Arguably, stories about women in science are all hidden in some ways. You might have heard the name Marie Curie, but how well do you really understand her story and just how revolutionary she was?

S&F: The triennial Sloan Film Summit, bringing together all the Sloan-winning filmmakers from the past three years, took place at the end of 2017. What were the major takeaways for you?

DW: One of the things I really like about our Sloan Film Summit is that of the 120 award-winning filmmakers we hosted, over 60–or more than half–were women. There is an argument that once you change the storytellers, you change the kinds of stories they’re going to tell. By the way, I think a man can tell a woman’s story and a woman can tell a man’s story. You should be allowed to imagine yourself into someone else’s experience; I don’t believe art has to be limited in that way. Nonetheless, in the aggregate, when you have groups whose stories aren’t told and you empower people from those excluded groups to tell stories of any kind, they’re going to tell you more stories about that group based on their own experience.

One of our big events at the Summit that went very well was about episodic television, since everyone wants to write episodic series these days. We had the writers from HALT AND CATCH FIRE and SILICON VALLEY. The film program has been getting more technology stories submitted, which is great because that’s a world almost everyone can relate to, especially young people. Obviously, in any film or episodic series today people are using technology but that doesn’t mean it qualifies for us.

S&F: What would you say it takes for a technologically themed story to qualify for a Sloan grant?

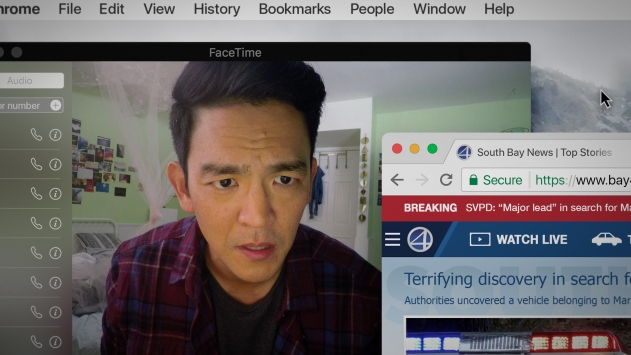

DW: It’s case by case. First of all, if it is a story about an inventor or technological innovator, somebody like Alexander Graham Bell, Doug Engelbart, Steve Jobs, Nikola Tesla, or Hedy Lamarr, then that’s an easy way to do it. But I think the way the SEARCH filmmakers [integrated technology] as a theme and a narrative frame was also effective, if more challenging to pull off. Then, stories like OPERATOR or THE SOCIAL NETWORK about working for technology start-ups, and that whole culture of trying to create a new technology that people will use, how does the new invention work? Those are great stories. [Those companies] also become a really interesting place to look at human relationships. Gender, race, all the things we care about are reflected in that world. It’s a very narrow world in some ways, or at least constrained, so it’s a good canvas. As you know, I’ve been encouraging screenwriters for ten years to look to Silicon Valley for raw material because it’s more accessible and filled with great, familiar characters. It’s not like having to study microbiology or particle physics. Everyone at least thinks they speak that language.

S&F: What stories has the Foundation supported that you are currently excited about?

DW: I’m excited about dozens of our projects, but two recent award-winners from Sundance come to mind. One script is about Katie Wright, the sister of Orville and Wilbur, and her critical role as a business woman in the development of airplanes. That script is a wonderful example of taking these iconic characters and seeing them from completely fresh angle. Another Sundance script I really like is based on a book called What the Eyes Don’t See by an Iraqi-American physician Mona Hanna-Attisha who blew the whistle on the drinking water in Flint, Michigan being contaminated with lead from the Flint River despite assurances to the contrary for both state and federal officials. The filmmaker is Cherien Dabis who is a Palestinian-American, so you have a woman from the Middle East as writer/director telling the story of another woman from the Middle East who played this heroic role in one of the most horrible and still misunderstood crises. It will take until 2020 to repIace all the lead pipes in Flint and residents have been instructed to continue drinking only bottled or filtered water until then. And by some estimates there are thousands of other areas in the U.S. with even higher levels of lead than Flint in their drinking water. Another script we’re now developing at San Francisco Film Society that I’m excited about is BELL, the complex, multi-dimensional story of Alexander Graham Bell told through the women in his life–from Helen Keller, to his wife, to his mother—and co-written by two women, Darcy Brislin and Dyana Winkler.

Doron Weber is the Vice President of Programs at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Director of the Public Understanding of Science & Technology Program and the Universal Access to Knowledge Program. Weber is author of Immortal Bird: A Family Memoir. Stay tuned to Science & Film for more on the films covered in this interview.

TOPICS