Marie Curie was the first person, never mind the first woman, to win two Nobel Prizes. Her full story has never been told. After receiving two Sloan grants through the Tribeca Film Institute, one in 2008 and one in 2011, A NOBLE AFFAIR will attach a director in the coming weeks. This screenplay focuses on the more difficult part of Curie’s life after her husband passed and she was publicly shamed. Co-written by NYU graduates Kathryn Maughan and Anil Baral, and produced by Baral, Neda Armian (RACHEL GETTING MARRIED), and Parisian company Haut et Court (COCO BEFORE CHANEL, LA VIE EN ROSE), A NOBLE AFFAIR stars Diane Kruger as Marie. Science & Film spoke with writer Kathryn Maughan, in the plaza of the Palace Hotel on her lunch break from her day job at an entertainment law firm, about the film.

Science & Film: What about the story of Marie Curie attracted you to this project?

Kathy Maughan: Anil Baral reached out and said, I want to write a film about Madame Curie, and would you be interested in co-writing, because I feel I need a woman on the project. Honestly, my first reaction was, oh science is scary; my sister got the science brains and I got the humanities. But, he sent me some books which were written after Marie’s papers were unsealed in the ‘90s and we began a dialogue. The book that was considered the definitive biography was actually published in 1936 after Madame Curie died, and was written by her daughter Eve Curie. It omitted this whole, huge, interesting time of her life. In the book she says, there were rumors which were published [about Marie Curie] and none of them are true. Actually, they were all true, but as memories faded and people died, with the papers being unavailable, that time of her life disappeared from the public’s consciousness. I also got the movie, MADAME CURIE, which starred Greer Garson and that ends just as Pierre dies.

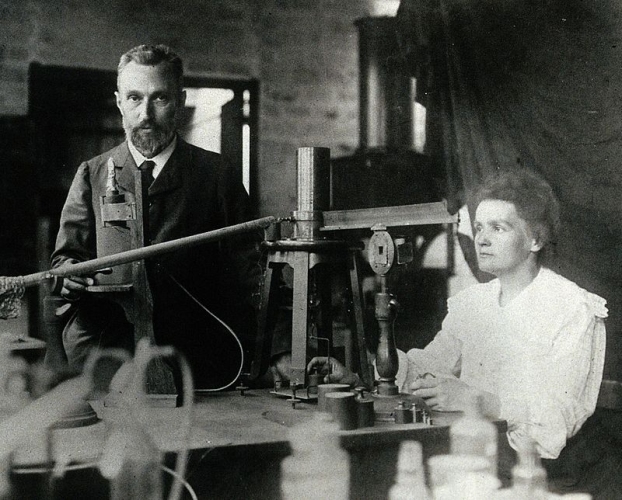

After her husband Pierre died, Curie was dealing with so many things–not just the run-of-the-mill misogyny, but xenophobia too, because she was Polish. She had been nominated for the National Academy of Sciences, and she had a Nobel Prize, but she was a woman and there were no women in the Academy so she was not voted in. Not one Academy member at that time had a Nobel of his own, by the way, but she lost by one vote. Papers had run editorials denouncing her for her gall, a woman trying to get into the Academy! It caused a huge stir. After that, she had an affair with one of her husband’s protégés, Paul Langevin. He was married. It was not his first affair, but because she was already in this precarious position in French society, when word got out (and it did get out because Paul’s wife made it get out—she found their letters and published them), that’s when total chaos was unleashed. People were mobbing her home, screaming at her in the streets, spitting, throwing rocks. At this same time, she was doing all of this incredibly important work. Her assertion that radium was an element–the thing for which she and Pierre were awarded the Nobel–had been challenged by Lord Kelvin in England because they had reduced it down to a salt, which is not pure. She called it a new element; he said, it is not an element, it’s a compound. When she finally got radium down to a pure element, they nominated her for a second Nobel Prize. This is around the same time her affair with Paul Langevin became a scandal. So, the Nobel committee wrote to her and said, had we known this, we would not have given you this prize, and we suggest you not come to Sweden to accept it. And she wrote back and said, excuse me, my personal life has no bearing on my professional accomplishments and I will be coming to Sweden to accept. Well, she didn’t let them take it away from her, but with radiation poisoning and the emotional turmoil of the scandal, her health deteriorated. She had to leave France to recover.

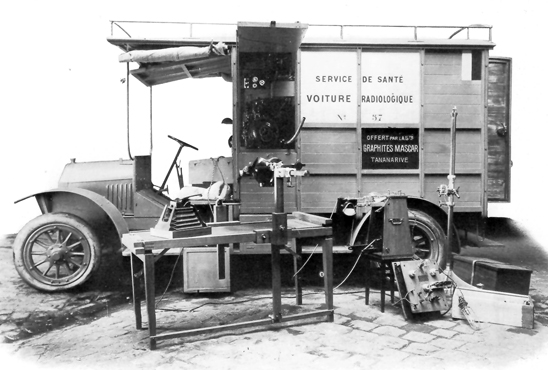

She invented these mobile x-ray units for World War I and actually drove them to the fronts. Previously, doctors would say, we have a gunshot wound, but where is the bullet? And they had to do exploratory surgery; getting a precise location saved so many lives. She trained her daughter Irène to also be a scientist. Irène and her husband [Frédéric Joliot-Curie] also got Nobel Prizes. They were instrumental in keeping nuclear secrets from reaching the Nazis. It’s just such an amazing story.

Marie’s whole childhood was incredible. When she was little, her mother and sister died of typhus, so she didn’t grow up as a very outwardly affectionate person. Poland had been occupied by the Russians. In school they were forbidden to speak Polish or teach any Polish history, but the teachers rebelled and they would teach that subversively. They had somebody on the lookout to see when guards was coming and then they would switch to Russian, and have to explain to the guard what they were learning about. Marie was in charge of that because she was the smartest in the class. She and her sister Bronislava both wanted to study after high school but they couldn’t afford it, and there was no university access for women in Poland, so they had to go to France. But they didn’t have enough money for both of them, so Marie worked as a governess for a family in Poland to pay for her sister to go to France to go to medical school. Finally, after her sister graduated, she sent for Marie who was finally able to go to France and study.

S&F: Would you say she was a woman ahead of her time?

KM: Absolutely. She was a woman who would say, you need to look at me as a scientist, not a “woman scientist.”

S&F: Why isn’t her story better known?

KM: I’m sure part of it is the fact that she was a woman, and there was all of that negative feeling toward her in France at the time. It wasn’t until the ‘60s that the National Academy of Sciences admitted their first woman, who happened to be a protégée of Marie Curie.

S&F: And the fact that she was Polish.

KM: Yes. All of these are themes which are, unfortunately, still so prevalent today. That’s why I keep saying, we have got to get this movie out. It’s a great time.

S&F: Do you envision your script as a biography?

KM: It is not a traditional biopic. It really just covers that unknown time in her life. We start when her husband dies, which is after a lot of Hollywood narratives end. We cover all of the scandal. So much was happening for her professionally at the same time, and she was trying to say, look at me as a scientist. Judge me by my work.

S&F: Will you be working with a science advisor?

KM: When I was writing the script, for dialogue I was writing, “science, science, science,” because I knew the characters would be talking about her work and I just couldn’t do it justice. Anil spoke to a few different scientists and we do have some credible-sounding dialogue, though the fact that it’s credible to me doesn’t necessarily mean it’s right. But we figured, at some point, we will get some professionals who will be able to look closely and say, this is what that means, or no, she wouldn’t say it this way, you need to rephrase. I just read that there is a science hotline.

S&F: Yes, the Science and Entertainment Exchange. They pair Hollywood writers with scientists.

KM: That’s great. I would love to do that, because it just bothers me when there are technical aspects of a script, or novel, and people in the know can see right away that something isn’t right. I know 99% of the population wouldn’t know what Marie was talking about, but the scientists who revere Marie Curie would. It would wreck their whole movie experience.

S&F: Has this project made you interested in writing about science?

KM: A good story is a good story, and if it’s about a scientist, absolutely. And I would prefer it to be about a female scientist, quite frankly, even though that has been a stumbling block.

S&F: How did the Tribeca Film Institute support help?

KM: We got the first grant in 2008 and that was a screenwriting grant. We used that to hold a couple of readings. When you’re starting out, you need validation. You need someone to say, she’s not crazy, she’s actually a good writer. Having the stamp of approval from Sloan and from Tribeca opened a lot of doors. Then, we got put on the Athena List this year so that opened doors as well.

S&F: Where are you now with the project?

KM: All of those problems we’re hearing about, women in Hollywood are now talking about -- they’re not new, and they’re very real. The subject of this film is a woman and she is not a superhero and she doesn’t throw flames, so people think, “This doesn’t scream ‘blockbuster.’” But it’s such an amazing story, and people who love the movies that tell amazing stories will love it.

S&F: But she did work with nuclear materials.

KM: I know. This woman is a real superhero. Her work is the foundation of nuclear science. She changed our world.

A NOBLE AFFAIR has been supported by the Tribeca Film Institute-Sloan Filmmaker Fund. Historian Karen Rader wrote for Science & Film on at the portrayal of science in biopics of important scientific figures including in the 1943 MADAME CURIE. Stay tuned to Science & Film to hear more about A NOBLE AFFAIR as it enters the festival circuit.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS