Lewis H. Latimer–African American inventor, patent draftsman, and poet who contributed to the invention of the incandescent bulb and much else–is the subject of a new feature film. Written by Jon K. Jones, LET THERE BE LIGHT was awarded a 2020 production grant by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation while Jones was finishing his MFA at Columbia University, and won its second Sloan prize also last year from SFFILM. We spoke with Jones about the film’s subject and its development.

Science & Film: Why are you interested in making a film about Lewis Latimer?

Jon K. Jones: We’ve seen a lot of historical dramas about important people in American history, and Lewis Latimer has a story that is profound—he was an exceptional person who made an exceptional contribution to the scientific community and American history, but he is not a household name. The story is about tracking his accomplishments as an engineer and inventor through the lens of his relationship with his wife, Mary Latimer. I took that angle because I thought, what if this is a true love story? His accomplishments, while exceptional, are something on the periphery of what he feels is most important in his life. That was my approach to telling the story.

Early on, I was set up to write a story about how Thomas Edison and a ragtag group of fledgling scientists invented the first motion picture camera and went on to make 190 short films. It was going to be my ode to film. As I was researching the timeline of that invention, Lewis Latimer’s name kept coming up.

Mary Latimer, 1882. From the Latimer-Norman Family Collection at the Queens Public Library.

He was the son of an escaped slave who ultimately became an abolitionist, poet, and friend of Frederick Douglas. He fought as a teenager in the Civil War and the Navy. He taught himself how to draw and became lead draftsman at one of the top drafting houses in Boston. He helped Alexander Graham Bell draft the patent drafts for the telephone. He published poetry about his wife and how much he loved her. It was so rich and interesting that, while I set out to do an ode to cinema, ultimately this was too juicy. I became far more interested in how to narratively construct a story that could encapsulate the mind of the inventor without chronicling every single invention. That is how that all started.

It’s exciting that platforms like SFFILM and Sloan are interested in helping the story be told. I don’t think there’s been a single person I’ve pitched this to who hasn’t been enthralled by such a person existing. His legacy is pretty legendary.

S&F: What has been the film’s development so far?

JKJ: Initially, I was to make this as a short film about someone who became impassioned to improve the incandescent bulb in order for him to see his wife better at night. It wasn’t long after I had won the Sloan Production Grant at Columbia that I had a lot of time and I thought, well let’s try to do a feature and I submitted it to the SFFILM Sloan Science in Cinema competition and won that as well, by expanding on the properties of the short.

Latimer's lamp [second row left], from The Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.

I want to tell a story of a free, Black, intellectual in the North surrounding by all these titans of industry. He very well could have been a titan of industry if he was white or if he even cared to do so—I get the feeling that he was a person who was curious to the point of excellence and had no real desire to become some hero of the world. I think he was just trying to get to the bottom of things because that was how his mind worked, and it’s a refreshing counter presentation to what we’re used to seeing with movies like THE CURRENT WAR. What about someone who was capable of doing these things, but had more important goals?

I’m doing more revisions on the screenplay. As much as I will go to the grave demanding that people receive this as a love story, I do want there to be so much respect paid to Latimer’s process and contribution.

S&F: What sort of affect has telling Latimer’s story, someone who it sounds like you’ve come to respect, had on you?

JKJ: The story is really inspiring; it is one of those rare opportunities to come to the realization that people exist who, even myself, given 40 lifetimes, wouldn’t accomplish the amount he did. My challenge with this going forward is taking Lewis out of the fable and into reality. It’s easier for me to reign in the magnitude of all that he is by focusing on the fact that this was a person who loved and fought and worked and was humble. You can rank him like a superhero or like someone who has a calling he wants to avoid. Finding the areas for growth for him, as an inventor and a husband, are quite excellent.

S&F: There’s an organization not far from the Museum of the Moving Image called the Latimer House. Do you know about them?

JKJ: Yes. I was meant to shoot the short version of the film over the summer of 2020 and in our production guide we’ve got, sit down and talk with Latimer House. Now, because we wanted to be COVID-safe and tell the short version of the story, we’re doing it as an animated film. Latimer House reached out to me after the SFFILM press release went out, and I’m actually talking to them on Friday! We’re having our first formal call then and I’m very excited to speak with them, because there’s so much that I still want to know. I’ve only read things then made my own artistic assumptions. I would love for someone who is involved with preserving Latimer’s legacy to weigh in.

S&F: You’re planning to make both the short and feature?

JKJ: I’m going to make the short as an animated version. We’re excited about how animation is able to reach broad audiences, particularly younger people, and it will have a different tone and style than the feature film, which is definitely period. I think both could be appropriate for conveying Latimer’s story to two very different audiences. The feature is a great deal more serious. The animated short is eight-minutes long in screenplay form.

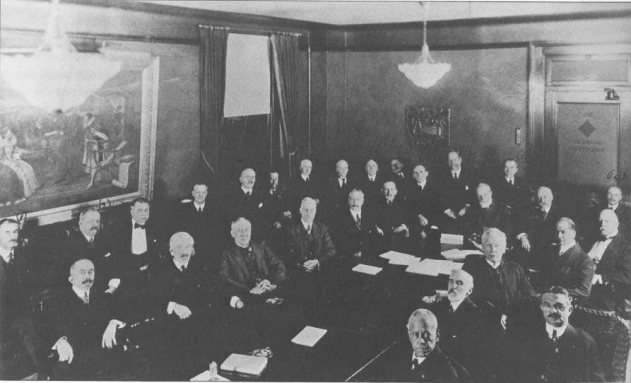

Lewis Latimer [right foreground], 1918. From the Latimer-Norman Family Collection at the Queens Public Library.

The feature is also a little sexy. It’s about a relationship—there’s intimacy. It humanizes the two of them in this way. It was important for me not to treat Mary as though she was just some supporting character. It’s very much her story too. Less has been written about her, but from what I’ve been able to gather, I’ve created a character who I think is not only Lewis’s perfect match but is a defender and an opponent and a guide. I want audiences to fall in love with her in the way that Lewis is.

♦

Stay tuned to Science & Film for more as LET THERE BE LIGHT develops.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS