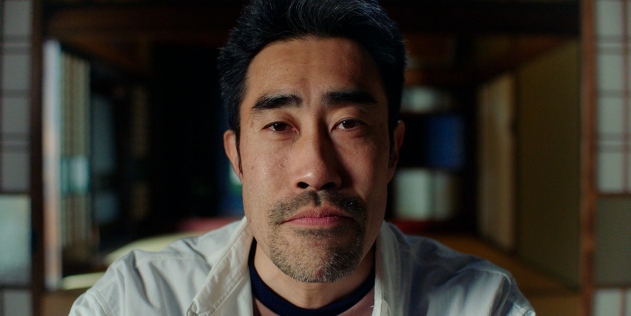

THE CONTESTANT, a documentary by Clair Titley that made its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, looks back at one of the first reality television shows. In Japan in 1998, a young, aspiring comedian named Tomoaki Hamatsu, nicknamed Nasubi, won an audition that resulted in him being left naked, without belongings or food, in a room and told that he needed to fill out magazine contest coupons in order to survive. Once he received prizes equivalent to one million yen, he would win. What became an extremely popular show—DENPA SHONEN: A LIFE IN PRIZES—was produced by Toshio Tsuchiya. During the course of his 11-month imprisonment, Nasubi suffered severe physical and psychological distress. At Toronto, we sat down with Clair Titley to discuss how she thought about presenting this complicated subject matter.

Science & Film: What drew you to this story?

Clair Titley: I came across the story when I was doing some development research with another project, and I went down one of those internet rabbit holes where you kind of go, this is interesting... and then you get a bit lost. It's such a mad story with so many twists. Every time I looked into it, there was something even crazier, and there was another twist and another twist. Even when we were making the film, more twists would unfold.

I was fascinated by why Nasubi had stayed in there, which is the question everybody always asks. I was also [interested in] how this could happen, how it came about that somebody could make this show. But I didn't set out to make a film about reality TV, or the history of reality TV. It's definitely a theme, but I don't feel that's what the film's about. For me, it's a film about connection and about a man who goes searching for connection potentially in the wrong places. But what I really do love about this film, and from the moment we started making it right through until screening it, is that everybody who watches it comes up with a very strong idea of what it means to them. I'm sure that happens in a lot of films, but particularly with this one, it feels like everybody has a strong feeling about what it's about and it might not be what I intended it to be.

S&F: It's a really heartbreaking story. Was it challenging to engage Nasubi in the present telling of it?

CT: We were really cautious from the beginning about not re-traumatizing Nasubi. Consent was a very important part of the process of this film. I worked with Nasubi to make this film. We'd always talked about the film being a collaboration, and he had no editorial control and he understood that, but I wanted to make it with him, with his consent. We always checked in and told him what we were doing, which direction we were going in, I asked him for visual ideas. He was very much involved in the whole process. I think for him, this was his opportunity to properly tell his side of the story. He's done short interviews before, but he really got a chance to delve in there and explore it, which I know he hadn't really had an opportunity to do before. I think it was also timing-wise, he just felt ready now, it felt like the right time for him to do that.

Image courtesy of TIFF

S&F: In terms of the dynamic between the producer Toshio Tsuchiya and Nasubi, where Nasubi is very articulate and reflective, Tsuchiya is much less so except in some moments–I'm thinking of when he admits they're both sons of policemen.

CT: [Tsuchiya] sort of says that he has trouble connecting with people. He's quite detached from things. I had a childhood where I was traveling around a lot as well, my father was Army, not police, but in a similar way. We've all come out of it quite differently, Nasubi, Tsuchiya, and I, but I can kind of relate to that feeling of moving around in your childhood and having to make friends again, start from scratch, so there is this kind of uncanny similarity between them, but they're also the two most opposite people that you could possibly get as well.

I think Tsuchiya was very honest [in the film]. He was very forthcoming. I don't feel like he held back. He kind of like was like, if I'm going to do this, I'm going to do it. And he said this to Nasubi beforehand, he said I'm going to be very honest and I'm going to just say what I feel. He totally approached it that way. I didn't feel like he self-edited. He was really brave in that way.

S&F: How much footage were you working from? What was the process of accessing it?

CT: Tsuchiya, the producer, was really integral to helping us get the footage. He helped work with the network and helped us with negotiations. So he was really quite integral to that whole process. And there was a lot to watch. But we didn't have any dailies because all they'd kept was what was broadcast. We found quite a bit on YouTube and Japanese eBay. We've been mining old VHS tapes in our research. It was quite something, going through that methodically and working out what he won, when, and how many days he'd been inside, and what was going on.

It was a lot [of footage], but it wasn't as much as you'd think. I didn't have a year and a half's worth of footage to watch, because it was only what was on the show, and the show they would cut down to like, I can't remember what it is, but a few minutes per episode.

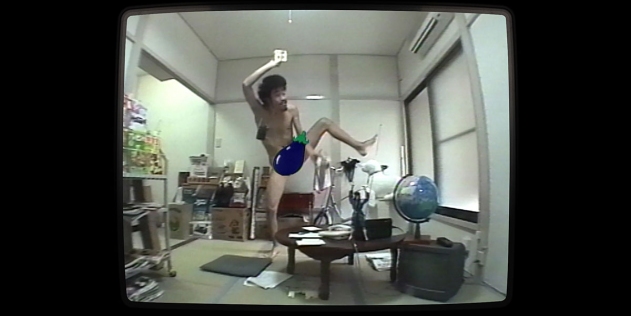

Image courtesy of TIFF

S&F: Why did you decide on the English dubbing and graphic translations?

CT: There were two things we wanted to do there. One was, because we only had the finished show, I really wanted everybody to have this immersive experience so that you got to understand if you don't speak fluent Japanese what it's like to watch without reading ten subtitles, or whatever it is. So that's why we translated it into English. We had to take off so many sounds in order to take off the Japanese, we then had to almost rebuild it from scratch. The sound guys have just done an amazing job of re-recording some of that music. But the other thing, conversely, we wanted to do was give you a sense of what it was actually like for him in the room without all these "boing boing" noises and without all the cartoon graphics on it. The VFX guy Jason has done this incredible job of stripping everything back. We didn't have layers, we just had this pretty poor quality footage. He stripped everything back so that you can actually see what it was like [when Nasubi was] in the room by himself.

S&F: That helps explain how audiences at the time may have had a hard time comprehending what emotional state he was in.

CT: They didn't see that stuff at all, they didn't see those images of him just on his own. All they saw were the bits of him dancing, jumping around, or if he was just writing postcards, which he was most of the time.

S&F: The livestream part was also really interesting, I was curious about that. This is basically the dawn of internet culture.

CT: It was actually only on for a short period of time. It was very typical of Tsuchiya who always seems to be at the cutting edge of things, even now. He has moved out of television, and he's doing virtual reality stuff. It was the early days of livestream. I don't know how many people had the dial-up speed to actually be able to access it. On top of that, it just crashed the system. So I don't know how long the livestream went on for, and I'm not sure whether they continued it when he was in Korea. But I don't I don't think it was that accessible for people.

Image courtesy of TIFF

S&F: Nonetheless, the way Nasubi talks to the camera it's almost like he's trying to communicate--like he hopes people are watching.

CT: He talks to the camera. It reminded me sometimes of the Tom Hanks film CASTAWAY when he talks to Wilson the football. He [Nasubi] doesn't believe it's being broadcasts but it's a focus sometimes.

S&F: You mentioned you are interested in the psychology of why someone would agree to do this, and the way Nasubi is at times sort of performing for the camera I wonder how much that played into the psychology of how he managed to stay in there...

CT: I don't know. I used to work on a rig show and when people first come in the room, they're very aware of camera and they seem to be playing it up. But after a while, they do kind of forget that it's there. I'm not saying Nasubi forgot for the entire duration, but there are definitely times he forgot that it's there.

I think his diaries were more so [his way of trying to connect], I think that was his way out. He wrote a lot in his diaries. A lot of his diaries are actually really funny as well as being quite tragic in places as well. He writes very eloquently. When they say "A Life in Prizes" at the start of the show, there's a graphic of a quill and an old piece of paper. The reason for that is because it's them referencing the fact that he's quite old fashioned--traditional. His writing is quite traditional kanji.

S&F: Have Tsuchiya and Nasubi seen the final film?

CT: Both Tsuchiya and Nasubi have seen it. Nasubi wrote a lovely little note for me to read at the screening, which I should give to you. He said: “I'm in a complicated state of mind, mixed with anxiety and expectations about how the people who watch this movie feel. I think this kind of work is probably often made after the main character's death. But fortunately, I'm alive and well. And many people may think that I'm an unhappy and poor person who lives a life hit by tragedy, but I'm never an unhappy person. Because I know that if I have a reliable friend who shares just an inch of happiness, and that small happiness supports me, I can live well with a smile. I hope that people have seen this movie well think about what is important to living and live a rich life even a little.”

It's very Nasubi to feel anxious about what people are going to think. He is a genuine, good soul. He says he doesn't get angry. And I think weirdly, people get frustrated by that because they want him to be angry at Tsuchiya and the show. That's not to say he doesn't hold a grudge and that he hasn't been cross at some point. But he doesn't harbor a lot of resentments. He and Tsuchiya see each other occasionally. They do a lot of radio together, which I always find a bit unusual.

♦

TOPICS