A new exhibition, “Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today,” considers how the Internet has profoundly affected artists and their work over the past 30 years. Exhibiting the work of 60 artists, the show is at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and curated by Eva Respini, the Barbara Lee Chief Curator at the Museum, whom Science & Film spoke with on February 7, the day of the exhibition’s opening. “Art in the Age of the Internet” is arranged by theme: “Networks and Circulation,” “Hybrid Bodies,” “Virtual Worlds,” “States of Surveillance,” and “Performing the Self.” A number of video works are included in the exhibition, by artists such as Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Camille Henrot, Nam June Paik, and Pierre Huyghe, as well as two pieces by Lynn Hershman Leeson whose feature film TEKNOLUST was awarded a Sloan Prize in 2002 and screened in 2017 at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of the Science on Screen series. Science & Film spoke with Respini by phone.

Science & Film: In putting together this show, how did you define the Internet?

Eva Respini: We’re thinking about the Internet not so much as a set of technical protocols but as a set of social relationships, as a social construct that has profoundly affected our culture, our visual culture, and has affected how artists produce, see, and think about our world.

S&F: Two ways that the Internet has affected art are in its production and in its content. What are some pieces that come to mind from the exhibition that resonate with either category?

ER: There are some works in the show that are very technologically motivated that have either a live Internet connection or are looking at the specific architecture and protocols of the Internet. Then, there are others that are much more responsive to the cultural impact of the Internet and those tend to be works of painting, sculpture, or photography–analogue mediums, so to speak. We made the decision early on in the show to not make it a show of technology.

In terms of works that are looking at the actual technologies or architectures of the Internet, Trevor Paglen comes to mind. He has been thinking about visualizing the architecture of the Internet, and very specifically the architecture of mass surveillance programs that the U.S. government and the NSA in particular have enacted. Trevor has a series of photographs of the telecommunication cables under the ocean that have been tapped by the NSA. The Internet seems invisible to us: we think of the Internet as a cyberspace that doesn’t have an actual architecture but Trevor visualizes that. Another piece by him in the show is called the “Autonomy Cube” which is a Wi-Fi network that is available to our viewers when they’re inside the Museum. It connects you to a Tor router, which allows you to surf the Internet anonymously. Tor routers are used all the time by government agencies like the NSA; they’re also used by terrorists. They’re used by many people to browse the Internet in an anonymous way. Trevor’s goal with this piece is to have it in every university library and museum in the United States as an opportunity for the average person to surf the Internet anonymously should they wish to do so. That’s an example of an artist who is thinking very specifically about not just the physical apparatus of the Internet but also is allowing our viewers to participate in certain aspects of the Internet and think critically about how the Internet works today.

I would say the two works we have by Lynn Hershman Leeson similarly speak to the technological protocols of the Internet. Her works have a live Internet connection. Her “CyberRoberta” and “Tillie, the Telerobotic Doll” are two sculptures, dolls, that have cameras for eyes. You can log onto a website and surveil the gallery through these sculptures. Also, while you’re in the gallery you can see yourself seeing through those dolls’ eyes. It’s a great piece that, like Trevor Paglen, is thinking very specifically about the technologies of the Internet and surveillance.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Surface Tension, 1992. Courtesy the artist and bitforms Gallery, New York. © Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.

S&F: Going back to what you said about considering the Internet as a social construct, I wonder about the international nature of the show and whether the different ways that the Internet is used around the world, like in places where access to the Internet is limited, factored into your curatorial decisions?

ER: Absolutely. In our position in the U.S. and in the West we mostly have this idea that the Internet is everywhere and accessible to all, but in fact only about 40% of the world’s population has access to an Internet connection today. Over half of the world’s population does not have access to the Internet. And then of course, in certain places, the Internet is severely restricted. So we have thought about the idea of the Internet as a tool of resistance as well. There are a few artists who speak to that.

There is an artist aaajiao [Xu Wenkai] a Chinese artist, activist, and hacker who created a piece in the show titled “Gfwlist.” GFW stands for great firewall as in the so-called Great Firewall of China, in which websites are banned in China for people there. “Gfwlist” a sculpture made up of a thermal printer that spits out a kind of receipt paper with all of the websites banned in China by the firewall. It’s making that list very visible. Another piece that speaks to the idea that perhaps the Internet is not as neutral as we think it is, is a net art piece or a website that was developed by Taryn Simon, a visual artist, and Aaron Swartz, the programmer and activist who took his own life. The piece is titled “Image Atlas” and it’s a website accessible in our galleries and live on the web. It’s essentially a keyword image search that shows you what your search results would be in various search engines in different countries. If you put in, say, hot dogs, or the super bowl, you see what your image results would be in the U.S., Germany, France, Afghanistan, or Iran, or China. What you see is this great difference in what appears under your search term. It challenges the idea that the Internet is democratic and the same information is available to all of us; indeed it’s not. Even between say Germany and France, or U.S. and some Western European countries, the difference of the results is quite acute. Cultural context and geographic location do inform those search results, as do algorithms.

S&F: Since you began putting together this exhibition three years ago, how has your thinking about technology changed?

ER: I would say the artists in the show really helped me crystalize my own view of the cultural moment. Events like Brexit, and the election of Donald Trump. Post-truth was the word of the year according to the Oxford Dictionaries in 2016 and I was in the middle of writing my catalogue essay. There is the rise of “fake news” of course, and now talk about Net Neutrality; all this helped sharpen the argument for the show. I was much more overt in talking about and creating a conversation between works that had a more utopian view of the Internet, the dream of the Internet being about interconnectivity, sharing information and images across borders regardless of language, regardless of geographies. This is embedded in the piece “Internet Dream” by Nam June Paik, from 1994; it is the first work you see when you enter the show. This is in contrast to what I think currently is a deep suspicion of the Internet, a coming to terms with the fact that we live in these algorithmic bubbles and are fed information and images according to our world view, according to how we shop, and the ads we click on. There are works in the show that speak to that–I wouldn’t say dystopic idea of the Internet–I think much more nuanced understanding of what the Internet has become. The events in the recent year or two really did help sharpen that argument and make it more overt in the exhibition.

.jpg)

Lizzie Fith/Ryan Trecartin, Permission Streak (still), 2016. Courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Sprüth Magers. © Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin

S&F: What would you say the argument for the show is in general?

ER: The question we are asking very broadly is, how has the Internet changed art? We talk a lot about how the Internet has changed every facet of our lives. Every field, every industry has been touched and radically changed by the Internet if you think about how we shop, travel, date, how we present our private and public selves. So of course it’s affected art. The way we are answering this very broad question is through these various thematics, and through the lens of various artists. There is no one answer to that question, but it’s nuanced, complicated, and answered by artists from their particular viewpoint, subjectivity, their particular lens, medium, and what their concerns are in their medium. That is why it was important for us to have painting alongside moving image, alongside photography, websites, performance, sculpture, etc.

S&F: We all know how quickly technology changes. Did that concern you in putting together the show?

ER: It’s been open one day and it’s already out of date, haha.

S&F: That’s a constant concern. I interviewed two filmmakers who just made a film, SEARCH, which was at Sundance that takes place entirely on screens and is very much about the way that we live our lives online. They were saying that they knew the moment that they made the film that it would become in essence a period piece.

ER: There are two ways that I’m thinking about that question, which is a really good question. On the one hand, this show is actually looking back a bit. Our starting point is 1989 and what we’re trying to do is historicize works being made now with works from almost 30 years ago, and to create a narrative between generations of artists. Themes like threat to privacy and surveillance in a post-Snowden, Chelsea Manning, revelation world seem very acute and front of mind, but of course artists have been thinking about that for a long time. In that room about surveillance we have Lynn Hershman Leeson’s sculptures from 1995 and we have Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s installation “Surface Tension” 1992 to show that these ideas are not necessarily new. Yes, technologies have changed and socio-political context has changed and informed works, but there are some concerns that artists have been thinking about for a while. So that attempt to historicize allows us to not be so tied to this extreme present, which is a term that the curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist uses for our moment where everything is changing at a rapid speed. That’s one answer to your question. But then the other answer that I would say to you and I wrote in the catalogue is that this show is not the final word, by any means. I could have done this show probably ten times over again with the number of artists speaking to this topic in a really interesting, resonant, cogent way. In the book, I point to all the other exhibitions done on this topic and how indebted I am to all those exhibitions. There was a series of exhibits around 2000 at the Whitney and SF MoMA. One was called “BitStreams” and one “010101”. Those shows also were of their moment but have informed the work that we did. If the Internet has taught us anything, it’s that there is no such thing as the final word. There is no such thing as a history, one story, one cannon. I hope this is one marker, one moment in time, and an opportunity to step back and historicize some work but with the acknowledgement that we’re within this flood of information that is the Internet.

S&F: Lastly, I just want to ask how curating this show impacted your thinking about the Internet and art today?

ER: Virtually everything made today could be under the umbrella of this show because I’m talking about a cultural moment: the age of the Internet. The analogy is if we did a show of work in the 1960s called art in the atomic age. Again, this kind of cultural backdrop is really what I’m talking about rather than only works that are dealing directly with the protocols of the Internet. So in many ways, doing the show and working with the artists has given me really insightful understanding of our moment now. I would say it has given me inspiration in how important art and artists are in this very complex and divisive moment. To me it reaffirms how important artists are in not just holding a mirror to reality, but they are a part of creating our reality. Artists provide us the opportunity to step back, ask probing questions, be critical of our current moment, There are very few opportunities we have these days to do that. I’m still trying to remind myself on a daily basis that this is why I do what I do, why it’s important to foreground artists and give them a platform because they can help us understand our own humanity and our own selves in a time that I think is a very difficult time.

Frances Stark, My Best Thing, 2011. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome. © Frances Stark.

“Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston through May 20, 2018. Eva Respini has been Barbara Lee Chief Curator there since 2015, and was previously Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art. She has exhibited the work of Cindy Sherman, Vik Muniz, Walead Beshty, Yto Barrada, Robert Heinecken, Walid Raad, and more. Accompanying “Art in the Age of the Internet” is a catalogue, web platform, and a series of events taking place at 14 arts institutions in Boston.

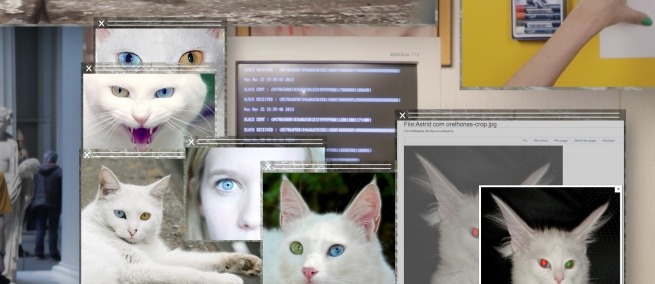

cover image: Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue (still), 2013. Courtesy the artist, Silex Films, and kamel mennour, Paris/London. © 2016 ADAGP Camille Henrot.

TOPICS