Making its world premiere in the Documentary Competition at the 2023 Tribeca Film Festival, Irene Lusztig's RICHLAND is a portrait of a surprisingly little-known town developed in the 1940s to house workers and their families who came to help manufacture plutonium at the nearby Hanford Nuclear Site. These reactors produced the plutonium for the “Fat Man” bomb that the U.S. dropped on Nagasaki. After World War II, people continued to move to Richland as the government focused on nuclear energy and on nuclear waste clean-up — an ongoing problem. Lusztig's film embeds in the conflictual culture of this community. We spoke with her before the film’s premiere about her research, approach, and how her film compares to other nuclear films.

Science & Film: How did you come to this project? What were some of the major resources you made use of for research?

Irene Lusztig: I was in Richland for a day in 2015, and this was while I was working on a previous film where I was moving through lots of different places in the U.S. It was filmed in 32 states and in all different kinds of communities. Through that project — YOURS IN SISTERHOOD — I basically spent one day in Richland. But during that one day, I got introduced to Trisha Pritikin, who's also in RICHLAND. She is kind of the only activist in Richland but she's someone who's a 'downwinder' activist who grew up in Richland and whose dad was a Hanford worker who died of radiation-related exposure. She herself has had lots of health problems. She ended up driving me around, I think she could tell I was curious, because there's all of this atomic stuff that's really visible — the atomic bowling alley, there's lots of nuclear-themed restaurants and things that you see immediately. She generously gave me a little tour and showed me the alphabet house where she had grown up. She also led me behind the high school to that back wall where there's this massive 40-foot-tall mushroom cloud exploding out of a capital letter that's the high school logo. I could tell that in all of this use of atomic imagery that there was something that felt kind of unresolved or unprocessed, or a question about the way this community was relating to its own history. That's something I'm always interested in. Most of my work starts with something historical that is still being negotiated in the present.

So that was the beginning of my interest, and I think I knew right away. I was like, this is a great next film project. I didn't start shooting until 2019, so it was four years of starting to learn more. I read a bunch, like Kate Brown's book Plutopia, and a book called On the Home Front, which is written a little more from within the community by someone who lives in Richland. It was the first book that was a kind of public exposé of the contamination that happened during the production years in Hanford. I also talked to types of people that you don't see at all in the film who are more experts and scholars. And then I did a lot of archival research. Most of my work starts with archives.

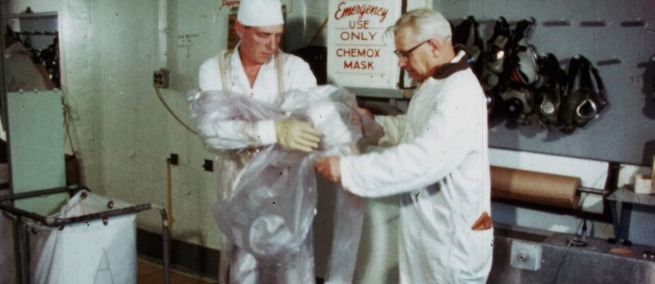

Film still from RICHLAND. Credit: US Department of Energy Hanford Collection.

Probably the most meaningful learning space for my research was this archive called the Hanford History Project that's in Richland. The Department of Energy/Washington State University kind of co-managed this archive project. It's an artifact archive. They have this huge, wild warehouse with all of these hard hats and furniture from Hanford and control panels, gadgets. and monitors. So I spent lots of time there, but also became friends with Robert Franklin, who's the archivist. That was really my touch point for learning a lot about the community. I would go back to that archive every time I was in town. All the archival footage in the film is from there and was just like in a cardboard box that nobody had really opened or processed.

S&F: Did you process and digitize the footage?

IL: Yeah, they were so chill, I think cause it's a smaller town. This would not happen in a lot of archives. They also didn't have a projector that worked well so there was no way to watch the footage without scanning it, without damaging the prints. So Robert let me take these 16mm reels in my suitcase out of Richland and I would give it to Rick Prelinger who would scan it, and then I would bring it back on my next trip. That doesn't usually happen in an archive but it was amazing.

S&F: That's very cool. How did you think about presenting the community as it currently is in conversation with the archive?

IL: I can say what I was really not interested in was experts, or people presenting a policy position. A lot of the nuclear films that I've seen tend to feature nuclear experts, and often they're pro or anti-nuclear films. I was not at all interested in that and had lots of opportunities to film that kind of stuff. I was really interested in feelings, and what I was calling nuclear feelings — ways to build intimacy with people that could get to these feelings about being haunted, or working through something in the past, or how people live with a history that's difficult. That's not the space that's most on the surface in Richland. I think Richland presents as a lot of scientists and engineers who want to tell you about science and technology.

It took a while to figure out how to get to those places, but that was always what my interest was, thinking about the emotional space of nuclear feelings and what it means for this community to live with a history that's troubling in a lot of ways, but also one that they continue to live with every day as a kind of ongoing condition. And I was interested in thinking about public spaces where history is being addressed or negotiated; that could be the local history museum that's in the film, that's this very sanitized presentation of atomic bomb production, where you never see any of the damage in Japan. It's just this story of: technology triumphs. There is also the parade that happened for the 75th anniversary of the Hanford Site, and these commemoration ceremonies that happened two years later. The one run by the National Park Service was actually the first-ever public commemoration in that community for the Nagasaki bomb. I was looking for these spaces where I felt like people were encountering some kind of narrative about history in a really active way.

Film still from RICHLAND. Credit: Helki Frantzen.

But also, there's a lot of landscape in the film. I really thought about that land as a kind of archive. That land is really special; it's very beautiful, but it's also kind of untouched by industry because of the time period when it was seized by the government. A lot of that land was never cultivated and never really touched or altered. People talk about deep time and geological time all the time out there. Those are some of the kinds of things I wanted to put in conversation with each other.

S&F: Could say a little bit more about what you were reacting to with the kind of scientific "experts" documentaries sometimes include?

IL: I'm just not interested in films that are about presenting information. There's a whole chunk of a documentary that's quite invested in verbal information that's being communicated where you learn about something. When I'm making film work, I'm always trying to think about what can film do that a book can't? I mean, there are wonderful books that have a great treatment of that history. But I feel like there are lots of people who've done that work of really getting into the science, and I think that's a great thing to do in a written form. I think film can do other things that are about presence and affect. Those are the things that I'm interested in.

S&F: In terms of the Japanese artist who comes to Richland during your film, did you know that was going to happen when you started shooting?

IL: I invited her. We actually met in a Zoom room of Hanford stakeholders earlier that summer. I knew that the National Park Service was planning to do this commemorative event and I just kept asking them: Are there Japanese people coming? Are you trying to engage that community? It started to become clear that wasn't happening. I knew there had to be some kind of Japanese presence or voice in the mix of the film, so I had hoped that ceremony would be a moment where someone would come to town. I just kind of made it happen because it wasn't happening on its own.

After we met in the Zoom room I reached out to her. She had introduced herself as an artist. And before I even had the idea to invite her, I was like, I just want to chat with her to learn more because she was very visibly the only Japanese person in this space of Hanford Zoom dialogue that was happening, so I wanted to learn more about her experience. Through that, we developed this idea that she would come. That was an intervention. It was an intervention that happened at a point where I'd already spent quite a lot of time in the community, and I thought this would be okay to do.

S&F: The history of Hanford continues to unfold, there was just an article in The New York Times about it...

IL: It was great. It's amazing PR for me [laughs].

S&F: That was just coincidental?

IL: Yeah. And it's so funny, because it's not new. That article could have been written at any point in the last 20 years, and it would have been largely the same.

Film still from RICHLAND. Credit: Helki Frantzen.

S&F: How do you feel about showing RICHLAND to a New York audience? Have you shown it to people in Richland yet?

IL: Yeah, I've shown it to a lot of the people who have been part of the film, and they've mostly been really positive about it, which is just great and more important to me than the New York audience. There's a long history of Richlands feeling like they’re a punch line or people just show up and are so the horrified by the display of atomic stuff that they don't really take the time to get to know the community with any complexity. I felt invested in making something where people in the community could feel listened to and feel like what I was presenting was showing the community and its complexity. A few people from the film are coming out for Tribeca, which is cool.

I think there's a way where people expect any film about nuclear anything to be very issues driven. There are some pro nuclear energy films that have come out in the past year, and then there’s antianti-nuclear, downwinder films that come from an activist space. So, I think there are a bunch of expectations around what a nuclear project can be. I don't think this film is even really about that, I think it's much more about how we live with history and what it means as Americans to process violent things in our national past. And people don't know Hanford outside of the region, which is interesting, so I think it'll be potentially the first time some people even learn about it. I'm curious to see how it's received.

S&F: The film answers this in a way, but do you feel like the community you found in Richland is the community that's left since the nuclear facility was active, or that it's still growing?

IL: It's a fast-growing urban area, which is interesting. Cleanup itself is a huge industry. There are new engineering, hydrogeology [jobs], all kinds of people that move to work at Hanford. There are huge science labs, Pacific Northwest National Labs, tons of scientists and science projects. There is also a huge agriculture and wine industry quite close by. Lots of people move there because they're priced out of Seattle. So, it's actually a growing community. Some of that is an artifact of cleanup, which is interesting. Like when the coal town shuts down, everyone really does leave and when the plutonium town shuts down, you can't leave because you have to attend to the 24,000-year afterlife of plutonium.

♦

TOPICS