AFTER YANG, a new near-future film, stars Colin Farrell, Jodie Turner-Smith, and Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja as a family coming to terms with the loss of their technosapien family member, the android Yang (played by Justin H. Min), purchased to be a Chinese brother for their adopted daughter. Directed by Kogonada (COLUMBUS) and adapted from a short story by Alexander Weinstein, AFTER YANG made its world premiere at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival and is in the Spotlight section of the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, where it was awarded the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Feature Film Prize. AFTER YANG will be released by A24 in 2022. We spoke with Kogonada about the film’s source material, its themes, and how he directed an actor to play a robot.

Science & Film: Was there an ethical question or issue that you were grappling with in setting AFTER YANG in a world with robotic companions?

Kogonada: Without it being the center of the story, [there is] this idea that once something is “on” it has a kind of consciousness, regardless of whether we define them as human—as if that’s the only way in which there is merit. Once you’re on, whether you’re a human or a clone or an AI or an animal or a tree, there is some significance to being off. That is in the background of the film. This exists in the short story as well. I remember talking to Alexander [Weinstein] who wrote the story. One of the things I loved about the story was that it was kind of dramatic how Yang malfunctions—he’s slamming his head into the cereal bowl—but there is something also real, like annoying [about it]; they didn’t immediately think, our child is dying. They thought, our appliance is malfunctioning. It is that sort of future where one begins to discover that this appliance might reveal something about what it means to be in the world and if there is some value there.

S&F: What else drew you to the short story?

K: It is the Pinocchio story: wanting to be human. It is tough being human; I’ve struggled with the existential crisis of being human. It feels like you’re trying to find meaning or purpose, but we also accept the way we came into the world as being an accident, whereas a robot has real purpose. They know that they were constructed, and they know why. I thought, maybe that would be satisfying. What if not being human is not as existentially fraught?

In the short story, I liked the idea that Jake [played by Colin Farrell] identifies as being very liberal, but when it comes to clones, he has a real opposition. There is a case to be made about why humans shouldn’t be cloned, but what side of that argument you’re on is interesting. I liked the idea that George [played by Clifton Collins Jr.], who Jake sees as a kind of Neanderthal, is the one who upsets his own view of himself politically.

S&F: How did you go about envisioning the setting in which AFTER YANG takes place?

K: My cinematographer Benjamin Loeb was instrumental in the conversations about how we were going to present this world. He shares a lot of my own sensibilities and approach. It made a good marriage of collaboration. We talked about the kind of future and the kind of space that we wanted to have this story exist in. I knew that I didn’t want it to feel metallic, glassy, or cold like often exists in sci-fi. I wanted to envision an organic world. I’m a bit of a formalist in the sense that I’m not doing handheld things that can warm up the space just because it feels so visceral, but I also love warmth. I wanted the space to feel warm and have a certain quality—suggesting a future that had been humbled by their ignorance of nature. To me, this is post-apocalyptic in the sense that it is a society that has rebuilt itself in light of a catastrophe. I knew that nature would be integral to the visuals and counterbalance the kind of stillness that would exist. There was a huge conversation about all those layers.

S&F: It’s obvious in the film that the cars are driving themselves, but also that there is a garden in the car. Why?

K: If there is future tech in this world, it is understanding how to utilize nature in a way that is less processed. Our production designer Alexandra [Schaller] has an eco-design consciousness so once I said, we want to play in that, she did some deep dives. There are things no one will ever notice, like a gutter on the outside that recycles water.

You see in Japan and other countries that they are trying to have more harmony with the world around them. I’m a modernist at heart, so it’s not like I romanticize a past that returns purely to something that isn’t modern, where racism and chauvinism exist. There is something about the progressive spirit that I think is important.

S&F: How did you go about directing Justin Min who plays Yang?

K: Justin was so sensitive and sincere to who Yang was, especially in relationship to Mika, his younger sister. A lot of what we talked about was the mystery of Yang. I wanted him to define Yang. Even as I was writing Yang, I didn’t want to feel like as the author I knew him and programmed him, so questions Justin had, it was up to him to define them. He had secrets about Yang that I didn’t know. That was a big part of Colin [Farrell’s] journey: who is this bot that seems like an appliance? Then realizing that he has a world in him. Even the interface with Yang’s memories, I didn’t that want to feel like it was a desktop and something we were familiar with, I wanted it to feel surprising. There is something about that uncertainty that some sci-fi literature explores: we build something and don’t fully realize that it has its own reality. Usually that’s threatening, but here it’s a little more philosophical.

S&F: Did you work with any science or technology advisors?

K: I had a good conversation over tea with the author, who had done some of that research. The sci-fi that I love tends to be lo-fi; I don’t fully like the ones that get into the weeds of the tech itself or the gadgets. It’s obviously a big part of the story and I can appreciate the films that get into the details, but I never wanted it to be a distraction in the film.

Also, I felt so honored in regard to the Sloan Foundation identifying AFTER YANG. We had, among ourselves, real conversations about the groundedness of the film and how technology evolves but doesn’t eliminate the technology before.

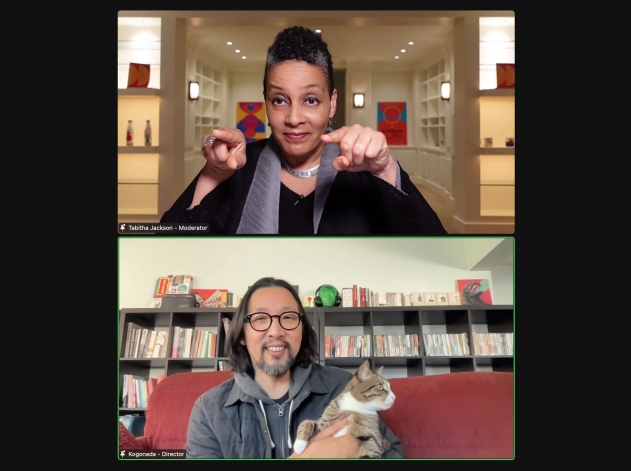

Sundance Festival Director Tabitha Jackson and director Kogonada at a virtual screening of AFTER YANG at Sundance. © 2022 Sundance Institute.

S&F: You do touch on the spyware potential of Yang in the film, and that was a fear that resonated with me. Was that part of the source material?

K: No. In the book Yang doesn’t have a memory bank, it’s just the father recalling his own memories. Russ [played by Ritchie Coster] is probably as close as the film gets to someone who represents something. His conspiracy over spyware is not unfounded. The nice thing about making films and not writing an essay is that you can present ambiguities. I feel like spyware is problematic and a real conversation [needs to be had]. What Russ brings up I felt was complicated and isn’t to be dismissed. I am now working on something… All to say, I am very interested in those conversations in regard to how we think about our society and our future.

♦

AFTER YANG is written and directed by Kogonada. It is produced by Andrew Goldman, Caroline Kaplan, Paul Mezey, and Theresa Park. The film stars Colin Farrell, Jodie Tuner-Smith, Justin H. Min, Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja, and Haley Lu Richardson. A24 will release AFTER YANG this year.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS