Over twenty years ago, Jim Berry made the Sloan supported, 20-minute narrative film SEMMELWEIS, inspired by the life of the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) who discovered that hand washing could save lives. Working in a maternity clinic in a Vienna hospital, Semmelweis was trying to find out why the hospital had such a high mortality rate; mothers were dying from a bacterial infection colloquially known as childbed fever. He discovered that doctors were often going straight from the hospital’s morgue—where they were performed lengthy autopsies and studies on cadavers—to the maternity ward, thereby infecting women. Hence, Semmelweis tried to institute a policy of rigorous handwashing. It wasn’t a given, though, that people listened to him. Some biographers suggest that his style of communicating his findings turned his colleagues against him. Semmelweis was ultimately ostracized by the scientific community and ended up dying in an insane asylum at the age of 45.

Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the world, the importance of hand washing to staying healthy is on everyone’s mind. We’ve taken the opportunity to revisit the film SEMMELWEIS and to speak with Berry about this landmark discovery and his fascination with the character of Ignaz Semmelweis.

Science & Film: How did SEMMELWEIS come together as a film, and why did you make it?

Jim Berry: I made this short movie as my thesis at NYU, and then I got a Fulbright to go to Hungary to produce a feature-length film script. This was in the early 2000s. [The feature script] was optioned for most of the 2000s, and Bruce Beresford was attached to direct at one point. We had different actors at various points committed to playing the lead. It sat there for a while. I have steeled myself for the day when I will read that [a feature film about Semmelweis] is going to be made and I’m not going to have a part in it [laughs].

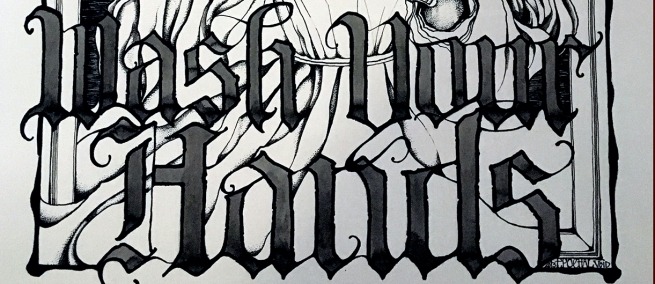

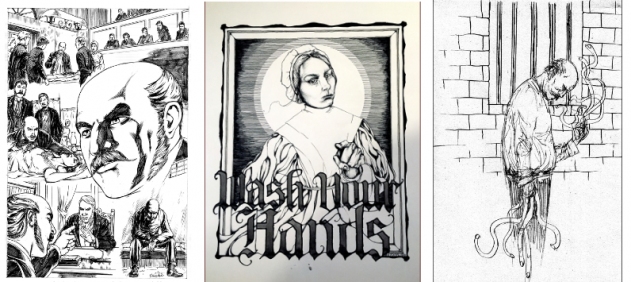

Meanwhile, I’ve always had a really deep affinity for comic books and graphic novels. About five years ago I adapted the screenplay into a graphic novel format, and I’m trying to push that out there to get it funded. I’ve also always been a fan of Gothic, psychological horror, and I saw a lot of possibility in the story for nightmares and Gothic storytelling. The idea of doing the graphic novel is to flesh out the entire story and to include who he was, where he came from, what happened to him.

Illustrations (left to right) by Zachary Sterling, Juan Jose Ryp, and Val Mayerik

S&F: What attracted you to the story of Semmelweis to begin with?

JB: The thing that attracted me to the story was this notion that we have to keep our minds open to new ideas. When we look at the idea of washing our hands, at the time it seemed like such a burden and such a bizarre concept to people. At the time when Semmelweis lived, there would be a basin of water, and it would be dirty, disgusting, bloody water–[rinsing hands] was sort of an optional deal. Their smocks being disgusting and stinky was sort of a badge of honor.

The whole idea that is so clear to us now, that washing your hands prevents the spread of infection, to them it was seen as an annoyance. He made that connection, and he was persecuted [because of it]. There are so many layers to the struggle that he went through. I thought it had a lot of parallels to things we deal with now. It’s so obvious the things we should do that we don’t do, and in 100 years from now if we’re still around we’ll look back and say, oh my god, can you believe people had these attitudes?

S&F: What are some myths about Semmelweis that you would like to set straight or explore in a longer iteration of the story?

JB: The mythology is that he went insane because he was haunted by the screams of the dying women he couldn’t save, but the reality is that he probably got syphilis and then he started doing some crazy stuff like accosting citizens for having dirty hands. He was in this asylum, 45 years old, for just two weeks and he died. They probably beat him to death, but there is this mythology that on his last dissection he was cut and died of blood poisoning. So he died of childbed fever/blood poisoning in the asylum.

There is a lot of material there. It’ll make a great movie someday [laughs]. You’ve got to think there are people meeting right now thinking, we’ve got to push this out immediately.

Illustrations (left to right) by Ron Randall, Epochal Void, and Ben Templesmith

S&F: Knowing the story so deeply, are you seeing any part of history repeat itself right now?

JB: Right now, people [are] saying you have to wash your hands and other people [are] just running warm water over their hands. No, you have to use soap and warm water. Semmelweis's deal, which got him in trouble, was using a heavy solution of chloride of lime in water. When I was researching the film, I made a bleach solution in a one-to-one ratio to see what it was like; you stick your hands in that and your cuticles, your fingers–it’s intense. You don’t want to get it on your clothes because it’ll stain them forever. That was a big piece of what eventually caused his downfall, that he was so insistent that everybody wash their hands in this harsh, caustic solution. They complained, this is really messing up our hands. He was so driven to save the lives of these women that there was no limit to what he would do.

A huge piece of the tragedy of Semmelweis is his personality, and that he was committed to a fault. That’s why he disappeared for years—look at Pasteur or Lister, there is no stain on their records. Compare that to what happened to Semmelweis; those guys pointed back to him, though, and said, without Semmelweis we wouldn’t have had a place to start.

S&F: When did perceptions of him shift?

JB: Now, in Budapest, there is Semmelweis University, statues of him, and he is now regarded as a cultural icon and national hero. I think things changed for him in the late 19th century and continue to change. In the early twentieth century biographers started to give him his due as a hero. Lately, there have been some more critical biographies of him, like Sherwin Nuland’s, more critical of his state of mind. Calling him out, I think rightly so, for being so overbearing. He was so committed—at what point does that become obsession? If you’re around someone who is obsessed with something, no matter how right that obsession is and how righteous–what happened to him during his lifetime is he had friends and contemporaries who said, you’re brilliant, you’re right, but you’re not going about this in a way that’s ultimately helpful to you or your patients. You can’t fight the system in that way.

SEMMELWEIS was made with support from a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation through their partnership with NYU, and is available to watch in full here. The Sloan Foundation has continued to provide support for stories based on Semmelweis’s life and work, most recently through development of the play SEMMELWEIS, starring Mark Rylance as Semmelweis, which is set to have its world premiere at the Old Vic in London.

This article features artwork that Jim Berry has commissioned of Semmelweis from graphic artists over the years.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS