Ecologist William Beebe, inventor of the Bathysphere, lived on sixty-seventh street in Manhattan and also underwater. He made record-setting deep-sea dives in a steel, pressure-resistant sphere. Beebe and his team–many of whom were women–also made a number of playful, fact-based films with scenes of fishes dancing, scientists fishing, and specimens being prepared, along with cartoon renderings of sea creatures. A stunning exhibition, of illustrations, diagrams, notations, newspaper advertisements, publications, and a live-action and animated video from Beebe’s 1927 expedition, is now on view at The Drawing Center in New York.

William Beebe, born in Brooklyn in 1877, was one of the most famous men of his day. Coincidentally, he went to high school in East Orange, New Jersey just three miles from Thomas Edison’s Black Maria, the world’s first film production studio, which was then in full production. Beebe had a long and prolific career, working through both World Wars and publishing 24 books in his lifetime.

Beebe started his career as an ornithologist but made his name when he turned to sea life and became a marine biologist and ichthyologist. He established the Department of Tropical Research (DTR), a field-based group of scientists and artists of both genders that explored primarily in South America. Their first research base was founded in 1916 in the jungle of present-day Guyana. Ultimately, the DTR became a part of the New York Zoological Society, which is today the Wildlife Conservation Society based at the Bronx Zoo.

William Beebe made a world record by diving 3,028 feet underwater in the Bathysphere during a 1934 expedition in Bermuda. The deepest point of the ocean is about ten times that, 35,787 down, which was only reached in 2012 by film director James Cameron. Beebe, like Cameron would, helped engineer his own submersible to reach that depth for the scientific purpose of collecting specimens. Beebe’s submersible vessel was called the Bathysphere, designed and manufactured with entrepreneurial engineer Otis Barton. It was first put to use underwater in 1930.

William Beebe and Otis Barton. ©Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

William Beebe and Otis Barton. ©Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

Members of the DTR used various methods of representation in order to document and study the creatures they were observing. As the DTR’s staff artist Isabel Cooper wrote in a 1924 article titled “Wild-Animal Painting in the Jungle,” “I have had to work out for myself many of the details of my profession. For instance, there’s no such thing as a school of snake artists, so when the problem of making a portrait of a snake presented itself I had to think up the technique for myself. There were many odd little worries connected with this problem, such as the invention of the proper anesthetic for deadly reptiles, to put them out of the misery of posing and yet allow the colors of life to linger from day to day.”

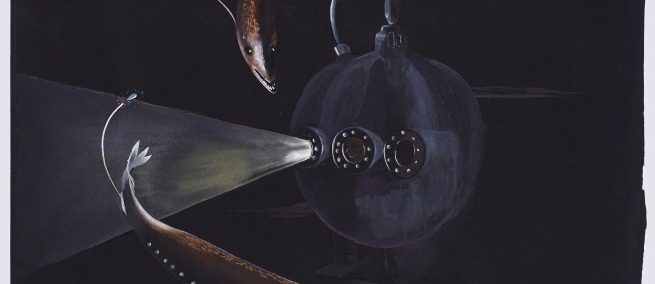

For sea creatures, DTR artists sketched underwater with steel pencils on zinc tablets. Expedition artist Else Bostelmann wrote in an article, “Notes from an Undersea Studio off Bermuda,” for the February 1939 edition of Country Life (excerpted in The Drawing Center's catalogue), “the greatest fun was actually to paint at the bottom of the ocean. After I had descended, my painting outfit was lowered by ropes from the boat. Generally I used an iron music stand for an easel on which was tied my frame covered with stretched canvas. My palette was weighted with lead and on it were squeezed gobs of color in all the rainbow hues. The use of wet colors under water in this way might at first strike one as impossible, unbelievable. But oil colors have never yet mixed with water, nor have they ever lost their brilliancy in this medium.”

Other drawings were based on relayed information from a telephone connecting the people in the Bathysphere, often Beebe or Barton, with the artists on the ship above. Then, specimens were brought to the surface, or deep-sea nets trawled for specimens. Staff artists used these as references to improve upon the accuracy of their drawings. Else Bostelmann continued in the 1939 article, “often those on my table vary from one foot in length to the dimensions of a pea—or less. The first time I was confronted by the scaleless, silvery or jet black little fish, my curiosity quickly gave way to enthusiasm. Through the microscope a new world of undreamed of beauty was revealed.”

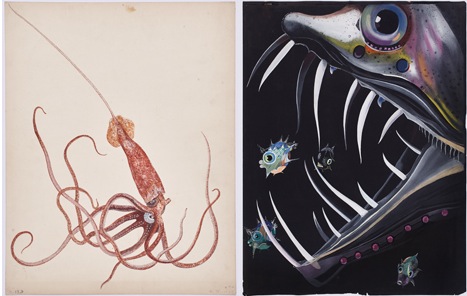

Helen Damrosch Tee-Van, "Long-spined Giant Squid," 1929 and Else Bostelmann, "Saber-toothed Viper fish Chasing Ocean Sunfish," 1934. ©Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

Beebe and his research team were interested in studying the behavior of animals. Film is one of the best ways to study behavior, because it records movement. Beebe was also committed to science communication; he travelled and lectured–often presenting films–at museums such as the American Museum of Natural History, and universities such as Harvard and Yale. Based on hours of footage taken during a 1927 expedition to Haiti, and Bermuda expeditions from 1930 and '34, the film in the Drawing Center exhibition was cut about fifteen years ago by the Wildlife Conservation Society at the Bronx Zoo, which holds Beebe’s archive.

Beebe’s films do not seem amateur. In a director’s report written by Beebe for the New York Zoological Society in 1927, he details the members of his staff which include Floyd Crosby as photographer. In his career Crosby shot over 100 films, the first of which he made with pioneering documentarian Robert Flaherty, and the most famous of which was HIGH NOON (1952). Other members of the DTR also went on to Hollywood fame and fortune. Members Ernest Schoedsack and Ruth Rose wrote and directed KING KONG (1933).

For the DTR’s 1927 expedition to Haiti, Beebe outlined five objectives. The third was to “obtain motion pictures of the life of a coral reef.” To do this, Beebe built his own camera. In a chapter of Beebe’s book Beneath The Tropic Seas (1928), his assistant John Tee-Van writes that because the purpose of the expedition was to study the behavior of fishes, “very little time could be devoted to photography alone.” He continued, “under such conditions it was imperative that the under-water motion picture camera be simply made, easy to operate, not too large or heavy, and capable of doing the most exacting work under the surface, using sunlight only as an illuminant.” The camera used on the expedition was a 39-pound DeVry that recorded on 35mm film. It was contained within a brass box with a glass pane in the front and fitted onto a tripod.

Tee-Van writes that he, Beebe, and Mark Barr (a physicist who was part of the DTR’s regular staff) constructed their camera in New York before leaving for Haiti. The DTR members conceived of the camera and it was then constructed by J. Schrope of the AMNH. Tee-Van writes that the DeVry camera was decided upon “after careful consideration of the smaller, motor driven cameras mainly because of its shape,–a rectangular box, about which it would be simple to fit a brass case.”

On the 1927 expedition, Floyd Crosby recorded 1,200 feet of film of coral reefs at thirty feet underwater using this camera. Beebe wrote that in the film, “living coral of many species, sea-fans, and fish are shown.” He continued, “the director in a helmet can be seen in various activities demonstrating methods of study on the sea bottom. Once a barracuda swims so near the camera that it more than fills the entire screen.” Beebe thanks George Eastman for contributing $100 toward film costs. Eastman, who founded Kodak, was also a well-traveled big game hunter. He had demonstrated interest in supporting expeditions. Eastman gave funds to the production of films by wildlife filmmakers Martin and Osa Johnson, who shot wildlife in Africa in the 1920s for the American Museum of Natural History to help raise funds for the Akeley Hall of African Mammals.

Floyd Crosby Filming. ©Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

In France at the same time that Crosby was filming with the DeVry, the filmmaker Jean Painlevé, thirty years Beebe’s junior, was also making underwater films. Painlevé filmed underwater using a Parvo camera, first patented by the Debrie corporation in Paris in 1908. The Parvo spun 35mm film, and Painlevé enclosed it as Beebe did in a waterproof box with side handles.

The Museum of the Moving Image’s collection includes the type of camera used by each of these underwater film pioneers. The collection holds two Parvo cameras from 1925. One was owned by Al Mingalone who made newsreels for Paramount News that played in theaters before feature films. The collection holds a DeVry 35mm camera which features a hand-crank for the film, and was manufactured by DeVry in 1926.

The Drawing Center exhibition is one of the most visible efforts to bring the incredible artwork of William Beebe and his team of scientists back into the public view. “I would say, [Beebe’s] major scientific contribution is the way he changed scientific conversation,” historian and exhibition curator Katherine McLeod told Science & Film. “Beebe was able to bring ideas about ecology and the relatedness of things in the environment to a popular audience. He worked to convey to New Yorkers and other urbanites that their cities were spaces of nature and enormous environmental processes and interactions. He was a major voice in the scientific community regarding the importance ofstudying interactions between living things, place-based work on evolution, and what we now call 'ecology'in general.” McLeod co-curated “Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expedition” with Wildlife Conservation Society archivist Madeleine Thompson and sculptor Mark Dion.

Jocelyn Crane Films Insect. ©Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

“Exploratory Works” is up now through June 16 at The Drawing Center in SoHo.