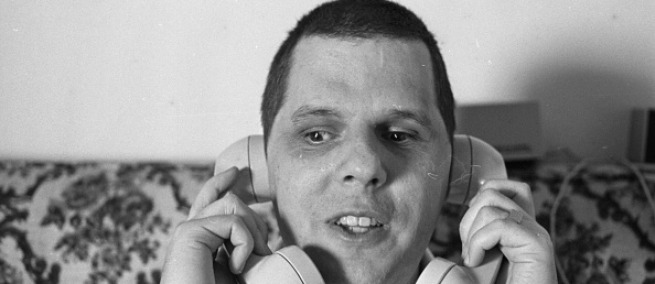

Making its world premiere in the U.S. Documentary Competition at Sundance, JOYBUBBLES tells the story of a blind man who was one of the first telephone hackers—called a phone phreak. Blending beautiful archival footage with narration by Joybubbles himself, the film follows him throughout his life as he continuously made innovative use of the phone system to connect with people around the world. Science & Film spoke with director Rachael Morrison and producer Will Butler in advance of the film’s world premiere.

S&F: You have some great footage and audio of Joybubbles throughout the film. How did you discover that?

Rachael Morrison: The first thing I discovered, because it's online, are 72 recordings of one of his Fun lines. And then as I started to go out and interview people, I met this woman, Cynthia, who's in the film--you might remember her, she has a frog on her shirt. She had recorded him telling his entire life story, like up until the 80s, when she first met him. She was going to write a book about him, but she never did. So she gave me these tapes, and it was at that moment that I realized, okay, this is going to be great, because he can tell his entire life story in this film. And then I found some recordings that someone gave me of two different speeches that he had given, one in Memphis and one in Denver, and then a family member found some recordings in a storage unit. So it's really a collage of all of those things.

Will Butler: So often, people with disabilities, frankly, don't get to tell their own story. And so, I think Rachael's vision for this was really to have him be the narrator of his own story. And that's not easy to do when someone has passed away, so unearthing those recordings, those very intimate, personal recordings was, I think, the key to all of this.

S&F: One of the things that stood out to me was, I think early on, when he talks about collecting crickets. I was just thinking of the sounds crickets make, and his ability to whistle.

RM: That's an interesting little moment where, you know, his sister is talking about crickets chirping outside when they're free and independent, and then when they bring the cricket home and it's stuck in this jar, it's not singing anymore. And that felt like a metaphor for him in that moment in his life, like feeling kind of stuck, and then later on, almost literally singing his way into independence by whistling.

S&F: Yeah. The trajectory of the film and his life is interesting too, because it almost seems like he regressed a little bit later in his life. In the end, he lived this very unexpected life. Had either of you heard of him before working on this project?

RM: I had not. I discovered him, unfortunately, when he passed away and The New York Times ran an obituary about him. That's when I first discovered him. And I didn't know about the phone phreaks. I didn't know people were hacking into the analog telephone system. I knew about computer hackers, but I had no idea there was this whole other history beforehand. He was really one of the first hackers to hack into a network. So I just found that to be unbelievably fascinating.

WB: There's this rich history of blind people being on the forefront of technology. Whether you talk about like the very earliest, you know, audio books to early synthetic voices, blind people have sort of always been active in this space, so I wasn't surprised by his story. But I think what's surprising is how influential he was, and that no one has written that. We're grateful to be contributing a chapter to that history, I think. And yeah, without giving too much away, I think his decision to embrace his childlike qualities is complicated, because I think like on one hand, people with disabilities are so often infantilized, right? But I think also we feel pressure to act like adults too. So I think actively reclaiming your childhood is sort of a radical act, and I think it's something that a lot of people wish they could do. Maybe it was a response to being told by society that he wasn't welcome, or maybe, you know, it was just him embracing his true nature. But I think it was like either way, it was a brave and sort of bold thing for him to do, especially during that time.

JOYBUBBLES

RM: And it was in response to trauma that he experienced as a kid, and trying to come to terms with that.

S&F: I imagine there were a lot of moments in the making of this film where you're listening to him tell his story, and you wanted to ask a follow up. You do a beautiful job interweaving his narrative with interviews. Is that how you dealt with not being able to communicate with him?

RM: I think it was getting to know him through the cassette tapes, and he's very open and honest about himself and his life, and then, yeah, like additional questions that I had, if they were appropriate, that's why I spoke with other people. But I think mostly they kind of come in to serve a function of adding to the history of tech, the history of hacking, talk about phone phreaking, and then in the second half of his life, it's sort of like realizing, there are all these people that didn't really know him, but they called his Fun line, and that made a really big impact in their lives. They still remembered him decades later, just from calling the Fun line. I just wanted to show that he really reached a lot of people.

WB: It's easy to romanticize the older tech too. But I still think that there're kids discovering technology for the first time today, who are probably having similar experiences. [He was] a boy who felt quite powerless, realizing that he was actually very powerful. And it doesn't really stop there. I think at first, you might think his superpower is his ability to whistle, but actually, that's just kind of a simple thing he does and I think really, where he shines and where his superpower really is, is like, his ability to consistently connect with people, and consistently make people happy, right? There was so much great footage of him talking, because he was, like, this prototypical like influencer or content creator, or podcaster. He had all these followers. But he wasn't like a brand or like a media company. He was just a guy who wanted to spread a positive message. That was so advanced for that time. I did feel like we were always in dialog with him.

S&F: How much did you think about the way technology has changed since Joybubbles's time?

RM: He wasn't just a phone phreaker. He was hacking the system and hacking his life, like his whole life. I love to think about his Fun line as being like a proto podcast, but also kind of hacking broadcasting. He didn't need to be on the radio. He made his own radio station with his phone. I mean, one of the funniest things I realized was that I needed someone to explain what a telephone book was, because people who watch this and experience this, a lot of them might not know. I asked David, can you explain what a phone book was?

S&F: How connected was he to the blind community, do you know?

RM: Oh, for sure. I think about half the people who I interviewed are blind. And he was pretty involved in the community in Minneapolis. Quite a few phone phreaks were blind. I interviewed Bill Acker, if you remember, he was a phone freak, he's blind, and he met Joybubbles in, like, the 60s, and they were friends for a couple of decades.

S&F: Will, I'm curious for you, what drew you to this project?

WB: I'm blind. I just don't think there are enough nuanced, complex stories of blindness out there. There's very few, really and very few stories that get beyond the trope of victim or a villain or a superhero. There are as many different types of blind people in the world as there are different types of people in the world. And Joybubbles was super complicated, just like everyone else. And so, Rachel is totally on board with telling a complex, multi-faceted story of a character who was none of those things and all of those things. And so to get a chance to be on a team to that that was doing that was awesome. And the fact that Sundance was the first to embrace the film is even more awesome. And so we're just really excited to add to the canon of good disability stories. And we hope that the various communities that this touches feel the same way.

S&F: Lastly--and this might be a conflict of interest--I want to ask about the score and how you how you guys thought about music?

RM: Yeah, that was Will Epstein.

WB: Wait, is there an Epstein conflict?

S&F: He's my brother.

WB: My gosh, amazing. No way.

RM: I love your brother. I'm so excited to meet him. He was the perfect person to score this movie. Taylor Rowley is a really good friend of mine. She's the music supervisor, and she knew his work. I don't think she knew him beforehand, but she knew his work. We love his score for the Nam June Paik documentary.

S&F: The film has to do in part with whistling and perfect pitch--it has its own music in it. Was there anything you took inspiration from there or wanted to stay away from with the score?

RM: Yeah, I mean, Will is highly collaborative, and we had a lot of meetings with the editor, and Taylor, and myself. It was sort of the four of us, you know, giving notes and collaborating, and Will sent us all sorts of different ideas. I think it's really beautiful, he sort of subtly put whistling into the tracks without it being just so obvious. I think his taste and style just really fit the film. And the song, "Bubble Joy." I mean, I can't believe Taylor found that. It was this weird record, like sort of a Christian record from the 60s or 70s. She found it a couple years ago, and we were just like, what is this, this is going in the movie.

♦

TOPICS