A recently published New York Times article has renewed interest in a wireless radio experiment conducted by astronomer David Todd and inventor Charles Francis Jenkins 100 years ago. In 1924, fueled by the persistent question of whether extraterrestrial life exists, public interest in Mars had reached a fever pitch. Yet, even if Martians were to exist and were attempting to communicate with Earth, how would humans receive such messages? Seeking a solution to this quandary, Todd enlisted the help of Charles Francis Jenkins, who had invented a device which converted radio signals into visual imprints on photographic paper. The results of the experiment were inconclusive. While an unexplained signal was received, there was not sufficient evidence to prove that the signal was of extraterrestrial origin. Todd remained a believer in extraterrestrial life, Jenkins remained not only skeptical but concerned that publicity around the experiment would tarnish his reputation.

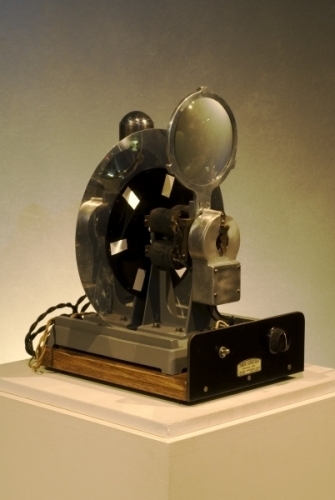

In the context of the search for extraterrestrial life and this experiment, Jenkins might be dismissed as a footnote. However, in the context of the history of the moving image, by 1924 he was already a pioneer. The year prior, Jenkins became the first person to transmit moving images to a receiver without wires and in 1925 his public demonstration of wireless audiovisual transmission led to a U.S. patent. By 1928, he opened the first television broadcasting station in the United States, airing four hours of programming each weekday. How did individual Americans access such broadcasts, decades before television sets would become a household item? Enter the Radiovisor, a kit amateurs could build at home and “tune in” to Jenkins’s programs. While a 1928 model resides at the Henry Ford Museum, Jenkins went on to improve the device for years, and the Model 100 Radiovisor – released in 1931 and sold for $69.95 each – can be seen at Museum of the Moving Image.

Image of the Radiovisor Model 100. Courtesy of Museum of the Moving Image.

Another scientist, Guglielmo Marconi, is briefly mentioned in the New York Times piece. Marconi’s speculation about the existence of extraterrestrial life is cited as having legitimized the widespread belief in Martian life at the time. Why? However misguided his speculation, Marconi’s reputation was bolstered by his creation of the first commercially viable long-range radio transmission system in 1895 -- a reputation burnished by the Nobel Prize he received in 1909. Marconi’s early work serves as the inspiration for Chris Farrington’s short film SIGNAL, which received a USC/Sloan Production Awards in 2008 and is one of the films in Sloan Science & Film’s online streaming library that can be accessed for free and used in the classroom. Watch the film here.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS