Written and directed by Radu Jude (BAD LUCK BANGING OR LOONY PORN), DO NOT EXPECT TOO MUCH FROM THE END OF THE WORLD combines various film techniques—including 16mm and iPhone recordings—to portray the frenetic life of a Romanian production assistant trying to meet the insane demands of the gig economy. The film stars Ilinca Manolache as Angela, who also takes the form of her alter-ego Bobiță when using a filter on TikTok. At times signing on to blow off steam, Angela/Bobiță monologues in ways that mirror misogynistic rants. However, they are performed as a form of extreme social critique. Winner of the Special Jury Prize at the 2023 Locarno Film Festival, the film is being released into theaters on March 22, 2024 by Mubi. We spoke with Jude about the ways in which social media footage can be in conversation with cinema, his appreciation for ambiguity, and his upcoming projects.

Science & Film: The way that Angela uses the cell phone in DO NOT EXPECT TOO MUCH FROM THE END OF THE WORLD is as an outlet, but I wonder if you also see it as a problem. Why did you want to include these TikTok videos? And how do you see their role in society?

Radu Jude: Oh, such a big question. I think that filmmakers are of two kinds from this point of view: ones who are searching for, let's say, the purity of the cinematic language and others who like to combine things and to mess it up. And I think I belong to both categories. Mostly I like to combine things and to make these collages and patchworks. Rauschenberg is my master. I think cinema has this power to include so many things and to transform them into itself. It does this in ways others cannot. You cannot put a film into a poem, but you can put a poem in a film so it's like a bigger umbrella. And under this umbrella, you can put many things and you can create connections between those things.

I tried to train myself in a certain way, and the only way to do it, to pay attention to it properly, is to try to expand my likes, or not to care so much about what I like or what I dislike, to try to see everything as interesting, at least, if not beautiful. So, then, if you really start paying attention to things, everything becomes interesting. In the world of images—because to make cinema is to create images—I discover that more and more I'm attracted to everything in a certain way, or I can see that a TikTok or an Instagram video is very interesting from a certain point of view. A TV image is interesting, a cinema image is interesting in another way. All are part of the same kingdom of images if you want, so why not? Working with them makes you feel a little bit like not being averse or against them. You know, in the same way, like John Cage, for instance, who is one of my heroes, at some point, he lived in LA for a while, in the 50s or 60s and there were a lot of radios playing things around—like a cacophony of radios. And he said that he solved this problem by making this piece with six radios turned on and off all the time. Working with those radios, he somehow tamed them. And now when he's going out in the street, he feels like they are playing his song, his piece, you know? So I think there's a little bit like that. Now whenever I see these vernacular images, let's say, of all kinds, I have the feeling it's part of my universe. So, I don't have a feeling that I have to judge them. Of course, I do, and I think we need to analyze them, and we need to judge them, I think we have to be judgmental. But, at the same time, I feel that because they belong to my universe in a certain way, I am alright with them. And I see them as more beautiful than before.

And then you asked me, what is [my perspective] towards society? Well, here, I think that the game is on. And of course, what we speak about these kinds of images is just the surface, because we know that these platforms can spy on you, that they're full of garbage of advertising, and it's full of garbage of the toxic politics and conspiracy theories and everything. All of this goes together with that. I don't know how can you separate one from another? But I understand that at the same time, it's not easy, and it's maybe not healthy for ourselves, but they are there. So if you ask me if I would want these things to exist? Well, in some cases, yes. Maybe in some cases, no. But they exist anyway. So, instead of crying over the death of cinema, maybe transform them into cinema? I don't know, it's the least we can do I think.

S&F: I wouldn't have thought of John Cage in relation to your work, but I can see what you mean, in terms of being attuned to things that are around you in a new way. And maybe not being fearful of them...

RJ: I think I am fearful of them. But then using them and working with them, you become less fearful, I have this feeling. I think here Cage is right. It's the same with people. You know, sometimes you have the feeling that someone is a terrible person–someone you don't know, or know only from online or from writing–and you meet that person and you might be completely surprised that he or she is not at all that terrible.

All of these things are, first of all, as I said, they exist and then you can use them like every tool or everything in the world, in many ways. You can do art with them, or you can harm with them, or you can lie with them, or you can kill with them. I don't know, it's the same with everything. We wouldn't give away a knife just because you can kill someone [with it]. I try to use them in a good way.

S&F: Could you tell me a little bit about what it was like on set? A lot of it takes place in the car, and using different camera modalities.

RJ: I don't have stories to tell you, it was really smooth. Ilinca, first of all, is a great actress, but also a great, great driver. She's used to driving in the chaos of Romanian traffic, so that helped us enormously. We made the film very fast. I think we shot everything in 21 days or something like that. The first cut was like three hours and 20 minutes, I don't remember. It was made quite fast according to regular standards in cinema. There was not so much time to think about that much. We were just going through filming, filming, filming all the time. The DOP is also very, very fast DOP. So everything was just doing it without thinking. In some cases, this is a good thing, in some cases it's not good because after a few days, I said oh my god, if I would have thought more about this scene or this shot, or that, I could have made it better, but it was too late already. The only thing I can have a complaint about is that after the first day of first days of shooting I had a terrible insomnia for two or three days in a row, and I was a wreck. So then I started to take and I still remain taking melatonin every evening, basically, because I cannot sleep. I'm afraid of being insomniac again. That was the only thing that was difficult for me on set, let's say.

S&F: I'm sorry.

RJ: No, it's just a trivial thing to have a kind of chat because otherwise, it was a non-eventful film. I don't have things like this happened or that happened. For other films I had more things like that. But for this, not really, it was really smooth.

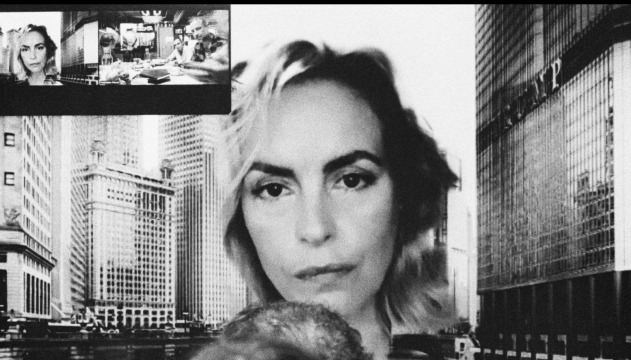

Ilinca Manolache in DO NOT EXPECT TOO MUCH FROM THE END OF THE WORLD. Courtesy of Mubi.

S&F: How did you capture the TikTok videos Ilinca was recording?

RJ: She was doing it with the iPhone. She was recording, she had the material in the phone, and then we transferred it to hard drives and use it in the editing.

S&F: And how did you find or create her TikTok avatar?

RJ: The avatar is exactly a creation of the actress–of Ilinca Manolache. She did it in the pandemic, while other people were reading Proust, or I don't know, doing something else. Having lots of sex, I don't know. She was creating this character and posting it on social media. She's a respected actress in theater, and people from theater are sometimes well, let's say, less open to these kinds of things. They said well, why doesn't she do a Shakespearean monologue instead of this junk? But she went on with this and I think it's brilliant. I really loved it and it's so much on the edge. Ilinca says about it that it's a kind of critique, a feminist critique, etc. I understand that and I agree with her, but in the same time, she likes it so much, you know, that you can feel there's something more fishy behind... a dirtier impulse. Which makes me remember that Jacques Rivette used to say about Verhoeven, when Paul Verhoeven made STARSHIP TROOPERS with these giant bugs, you know? Rivette said it's obviously that what Verhoeven says that he made the film as a kind of critique against the American military industry, etc. is just bullshit because he loves these bugs so much, that's why he made the film. [laughs] That can be turned back against me, because there was a friend that said, I really think it’s problematical this Bobiță thing. And I said, why? He said, because of all this. And I said, yeah, but it's a critique. And he said, yeah, but it's obvious that you like it so much to stage that. So. That's the mystery of life. We like dirty things.

S&F: For what it's worth, I think it does add another layer because she's enjoying it, it kind of makes you reflect on why you enjoy it too...

RJ: Actually, I think I like things on the edge. There was a recent article, I think by Beatrice Loayza, who also did an interview with me. That text I think was very good because she said that she likes things to be ambiguous. She was speaking about feminism, if Barbie is feminist, these kinds of things, and she said, she considers when things are ambiguous, they are more interesting. I believe it to be so, a bit like that.

Nina Hoss in DO NOT EXPECT TOO MUCH FROM THE END OF THE WORLD. Courtesy of Mubi.

S&F: Do you think you would use cell phone technology again in the process of filmmaking? What do you think the particulars of this aesthetic lend to the film?

RJ: If I'm gonna use it or not anymore, this I don't know. In some cases, yes. For instance, now I'm just finishing my two new montage films. One of them is with advertisements from the 90s in Romania. It is made together with a philosopher Christian Ferencz-Flatz. We use these images to put in montage, in editing. Another I did myself is a film with only \ screen recordings of a webcam from a place. So I'm using this already.

Speaking of quality, you mentioned quality, and I think you speak about technical quality. Well, I think this is an important issue. Cinema is a little bit less open than like for instance painting is, because in painting when a new technology appears it doesn't erase the previous one. When watercolors appeared, this didn't mean that oil painting is not anymore, or when pencil appeared, etc. Painters or people who do visual arts can use everything. I try to think of myself in the same lines–if these people can do it, why shouldn't we? Why can't I use a 16mm black and white and an iPhone? And actually, for my next feature film I'm shooting this summer, hopefully, I will shoot it on the iPhone 15. I'm really eager to do it in this way. Also maybe to tame it a little bit, to like it myself, to educate myself a little bit.

♦

TOPICS