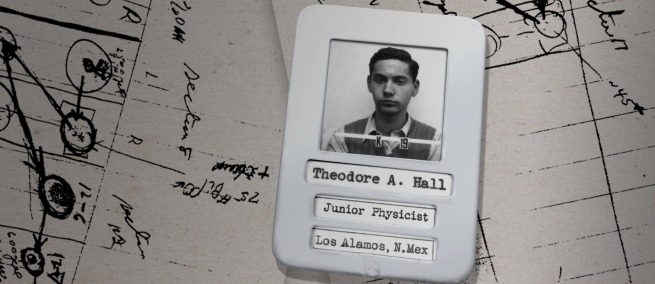

At 18 years old, Ted Hall was the youngest physicist recruited to work on the Manhattan Project with J. Robert Oppenheimer. As Oscar-nominated filmmaker Steve James’s new film A COMPASSIONATE SPY shows, he was a socially-minded scientist who was deeply disturbed by the potential for nuclear catastrophe and made the controversial decision to pass key information on the bomb’s construction to the Soviet Union. The film tells the story of Ted’s life and the context that surrounded his decision through interviews with his wife Joan, archival footage, and recreations. A COMPASSIONATE SPY made its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival and was just released by Magnolia Pictures into theaters on streaming platforms. We spoke with Steve James about why he was drawn to Hall’s story, the contrast to Christopher Nolan’s OPPENHEIMER, and the continued relevance of this history.

Science & Film: I'm curious if you can talk about how this project came to be, particularly thinking about the material you had to work with and the mix of archival footage, present-day interviews, and re-enactments.

Steve James: The project really originated with Dave Lindorff, who's a producer on the film, and by profession, he's a journalist. I met Dave because we interviewed him for the film ABACUS: SMALL ENOUGH TO JAIL. He does a lot of investigative work. He had written a piece about Ted Hall that appeared in CounterPunch online magazine, and which was an appreciation of Ted. Joan, Ted's surviving wife, read it and reached out to Dave and thanked him for it, and they struck up a relationship. Dave thought, I think there's a film here, she's amazing. He was right. So he reached out to me, and that led to us going to Great Britain for three or four days and doing that major sit-down interview with Joan that's the most significant interview in the film. I was just completely taken with her—both her personal story as well as this extraordinary marriage. And then when she showed that she had these other materials, archival interviews with Ted that were done before he died where he spoke with candor about all this, I was like, we have to do this story. When I left there, I said to my colleagues: Ted's story is extraordinary, but to me, this is as much a love story as anything. I wanted to tell the story through that frame of reference, because I didn't want it to just be history.

Ted Hall and Joan Hall in A COMPASSIONATE SPY. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

S&F: I know what you mean, in terms of how compelling she is. He's the subject, but she's the star of the film.

SJ: She is definitely the star.

S&F: As a director, how did you think about communicating what the stakes were of Ted Hall's scientific work and the information he passed?

SJ: We don't get into much of the science of it, because, well, it goes without saying I don't understand the science much. But we could have. We had a person who was a physicist who could have explained all of that. Daniel Axelrod could have done that, but I didn't ask him to. It was more important to me to provide the historical context that is really unfamiliar, I think, to a lot of people. And it's funny, even when you watch OPPENHEIMER, the Christopher Nolan movie, which I enjoyed a lot, you don't get a lot of the context that our film provides. Like, that the Soviet Union were being promoted by the US government, even the President, as this great ally. Most people don't have any idea that the Soviet Union not only lost over 20 million people, some estimates go as high as 30, but that World War II would not have been won without them. Americans have a tendency to think that when we entered the war, everyone was losing. We entered the war and suddenly, it's all, you know, we're routing the Germans and the Japanese, and we're the heroes. That is a misrepresentation of history.

All of these things were vitally important [to include in the film], because for you to understand why Ted arrived at making this incredible decision to do what he did, if you don't understand all of that, then it looks completely irrational on his part, or totally impetuous, and completely unwarranted. In my view Ted showed incredible insight at this extremely young age as to what might happen. He showed way more insight than Oppenheimer did. Oppenheimer didn't really get the insight until after they dropped the bombs on Japan. Ted was seeing this before they had even tested the Trinity bomb and had made this decision that he was going to do what he did.

S&F: So far as I understand, which is only in a limited way, Oppenheimer was a totally career-driven person, whereas Ted, as the title of your film indicates, seemed to be a very socially aware, politically conscious person that makes the context that you give in the film make a lot of sense.

SJ: Yeah, absolutely, I think you're right. Oppenheimer was driven. Oppenheimer was in charge. And it was a heady time. I mean, it was the most significant scientific undertaking in the history of humankind at that point—might still qualify as that.

Ted Hall in A COMPASSIONATE SPY. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

S&F: What do you think about this film coming out? Beyond the synergy with OPPENHEIMER, do you have any insight or feeling about why people are looking back at this time today?

SJ: When we started the film in 2019, which was when we first interviewed Joan, I remember thinking, I don't know if anyone will really care about this story, because nobody talks about nuclear war anymore. I mean, we're all convinced that we're going to bring the earth to an end via climate change. Or, in the last few months, A.I. The whole notion that we live under this cloud of danger from nuclear warheads has completely gone out of the public consciousness. So, I was like, I don't know if anyone will be interested in this other than as a piece of interesting history.

But then, as it went along, and when Christopher Nolan announced that he was doing his story, I remember thinking, wow, I wonder, maybe there's something in the air. I started to read about how China, which up until now has had a very limited nuclear arsenal, something like six warheads, is now in the process of ramping up considerably and plans to join Russia and the United States as a major nuclear power, which is frightening, to add another one. And then, I think with Putin's invasion of Ukraine and the possible threat of battlefield nuclear weapons... I think there's just been a rediscovery of this reality that we've really been living with all along, as if we need something else to worry about. But here we are. It is a fraught situation. It’s perfect timing too because we're living at a time where people are beginning to understand that there is a real cost to technological advancement and change. There's probably no greater example of that than this story.

S&F: One of the points that is brought up in your film is Ted's horror at other people's celebration of destruction, which feels very poignant.

SJ: It's an interesting moment in Oppenheimer when he's speaking to the people at Los Alamos, and he's sort of having a pang of conscience there. I haven't read American Prometheus, I don't know if that's true or if that was just complete poetic license by Christopher Nolan. It's a very strong scene. But whatever the truth is there, it can't really compare to the way in which Ted had seen this well before that, in my view. And I thought it was interesting in OPPENHEIMER too, and I respect the choice a lot to not show what happened to Japan with the dropping of the bomb, the way that's handled, but I felt like in our film, you absolutely needed to see some of that, because you needed to understand the horror, very explicitly, that Ted greatly feared. You need to understand that explicitly and to also understand it in this context that we spend more time teasing out than OPPENHEIMER. This was a completely unnecessary dropping of the bomb, and the real target of this bomb was the Soviet Union.

S&F: It's all a reminder that we're just sharing space together, country boundaries be what they may, but we all depend on finite resources and we need to not destroy each other because that means destroying ourselves.

SJ: Well, that's why to me when I first saw the archival clip of Ted when the guy asks him if he has a message for the next generation, the last comment in the film, I remember when I first saw that when I was in editing, and thinking, I think that is the last thing in this film. The thing that it made me think about as much as anything was today. Twenty-five years ago, he's talking about the threat of nuclear annihilation, before climate change was really on our radar in any meaningful way. But he could very well be speaking today about the world we're living in.

♦

TOPICS