NAM JUNE PAIK: MOON IS THE OLDEST TV, directed by Amanda Kim, is the first major documentary about influential avant-garde video and multi-media artist Nam June Paik. The film made its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and is opening theatrically in New York on March 24, with more cities and a broadcast television premiere to follow. MOON IS THE OLDEST TV is Kim’s debut feature. Steven Yeun reads Paik’s writings in the film. It is produced by Jennifer Biel Stockman, David Koh, Amanda Kim, Amy Hobby, Jesse Wann, and Mariko Munro. An original score was composed by Will Epstein [disclaimer: Epstein is author Sonia Epstein’s brother]. We spoke with Kim before the film’s theatrical release about her approach to the subject, the research that went into the film, and how Paik’s work inspired the film.

Science & Film: Can you talk a bit about your approach to representing Nam June Paik on film, in the medium he was often working? His work was often questioning both the possibilities and perils of media.

Amanda Kim: I had seen Nam June's work in museums before and was interested in it; it always had a very utopian bent. His work is so fun, and poppy, and colorful. What was super interesting to me when I dug in deeper was that Nam June was always aware of both sides [of the medium]. That is something that's kind of hard to understand when you just see his work quickly in a museum or you read a catalogue about him. I realized through Nam June's writings, especially, that he was interested in all these topics outside of art, and he brings them together in his art practice. It was super important for me that people could see that Nam June was thinking about the world at large, both the positive potentials, but also the fear of how [media] could be misused; that's something I hope people take away from the film. But ultimately, it's a positive message. At the end of the film, he says: death is having no future imagined. He is always exploring new possibilities; there is no end to what you might discover if you break the rules.

I think that's why it's felt so timely that this film would come out now, because I want it to speak to a younger generation, to our generation. A lot of people don't know who he is, which I was surprised by during the process of making the film—even people in the arts and culture sectors. The accessibility of his story was also really important to me. I could have made [the film] more experimental because his work is so experimental and he talks in riddles. But, like Nam June wanted his work to be accessible—by putting it on public television for example, not just keeping it in the art world—I wanted to do that as well with his story. And so, even things like avant-garde or Fluxus, I wanted to be able to explain that to people who have no interest in it or feel like it's alienating. It was super important to me that, instead of just reaching a niche art community, that I expand the audience.

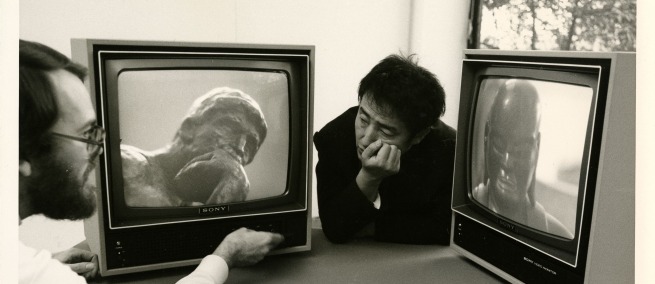

Photo from the Nam June Paik Archive at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

S&F: The film has a lot of incredible archival footage of Nam June throughout his life. What was the process of accessing that material?

AK: The archival process was definitely a long process. I was quite lucky early on when I hit up archival producer Wyatt Stone and he helped me for little to nothing, because he was interested in the subject. I would find things on the internet, and he had certain sources, but [the material] was scattered all over the world—it was not all in one place, and it was all in different languages. Also, old tapes go missing, or people didn't know that those things would be historical, and portapack tapes were very expensive so people would record over them. There were lot of heartbreaking moments where I was like, that thing is gone forever. But there are also a lot of happy moments where we discovered something that we thought was lost, or I would find through a friend that a friend of a friend was at an event and they recorded it, and there's like a snippet of Nam June in there which hasn't really been seen. And so that was super exciting.

I also got to connect a lot with the early video community, because a lot of those people were the ones present there with their cameras. It was a process of earning their trust, as well. I would offer to help clean their storage room or get coffee with them, and see them often, or Skype with them, or Zoom with them multiple times in order for them to feel comfortable sharing that stuff, because it's quite intimate and personal, and they might have use for it themselves.

S&F: Did you go to South Korea for research or talk to any of his family members who are still there?

AK: I did go to Korea. The estate is managed by his nephew, who is mostly in San Francisco or the Philippines. So, the family wasn't in Korea, per se, but in Korea I did speak to a couple people who knew Nam June from after his return and an early friend. A lot of the older Korean materials you have to access through the estate—the family archives—but they didn't have as many of the early archival material because he didn't return [to Korea] for so long. But what we did have was a great amount of archival MBC, KBS [footage]—these are the TV networks. Because once Nam June came back as a national hero in ‘84, they did such a good job of recording and archiving the rest of his career from that point on so we got a lot of amazing stuff from there.

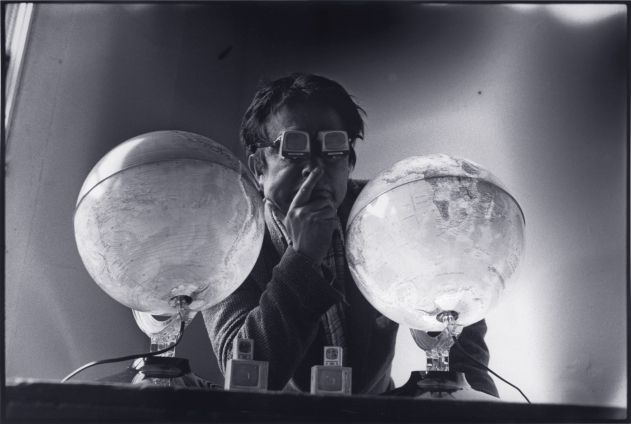

Photo by Peter Moore. ©Northwestern University. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

S&F: As the project came together, at what point did you start thinking about the music and sound of the film?

AK: Sound was a really, really important part of the film. Nam June is actually a composer; I think sometimes more than a video artist, he composes images. The way he edits and the way he plays with imagery and synthesizers is so musical. He says: you play it [a synthesizer] like a piano. I was thinking about that really early on. In selecting the editor, Taryn Gould is extremely musical, and she has a music background, and you can see it in the edit. And then I also thought of the composer Will Epstein really early on. I've known him since college. I don't know why this came up, but we were talking about John Cage one day, and I wasn't as familiar with Cage’s work, but Will was a fan and told me to read Cage’s biography. I always thought Will’s music was very beautiful, and I also associated him with Cage. Nam June’s father is Cage so there wasn't ever… I just always thought that Will would have been perfect for this project. I feel like Will has something in common with Nam June in that he can do both avant-garde and pop, and that was really interesting to me. I wanted someone who could both make something melodic and moving the narrative, while also being able to do more avant-garde, prepared piano type stuff. Will even did created his own prepared piano pieces as an homage to Nam June and Cage in the film. It’s rare that there is a composer who can really cross boundaries and genres like that.

S&F: I got a real sense from your film of the community and family that Nam June built for himself, and I also want to ask about his wife Shigeko Kubota. She’s still rather underappreciated, at least as compared to him. How did you think about incorporating her?

AK: Yes the community was, I felt, his family away from home. Everything included his new family: Cage, Ginsberg, Charlotte Mormon, Merce [Cunningham]—the boys—they were constantly in all of his works. I feel like Shigeko is an endlessly interesting character, and their relationship was very dynamic and complex. I feel like that could be a whole film in and of itself, and so I really wanted to focus the film on Nam June, because already that was a four-hour cut at one point without the romantic, couple story. To me, the first Nam June film should be more about his work and his ideas and the writings at the core of the film versus the personal dynamics. But yeah, I definitely didn't want to leave her out.

S&F: What’s next for you?

AK: I'm focusing on the release of this film, but definitely thinking about what's coming next. I want to be able to do both commercial documentaries, as well as like really arthouse [films]. Like Will with music and Nam June with his art, I want to bridge those gaps and do it all.

♦

TOPICS