SCENES OF EXTRACTION, by visual arts researcher and filmmaker Sanaz Sohrabi, is an archive-based essay-film focused on the colonial and extractivist expeditions of the British government as they located oil in Iran. The film made its world premiere at the 2023 Berlinale in the Forum Expanded section. It is the second film of a trilogy about oil that Sohrabi began in 2020 with her film ONE IMAGE, TWO ACTS. We spoke with Sohrabi about her body of work, modes of engagement, and what’s to come.

Science & Film: In ONE IMAGE, TWO ACTS and SCENES OF EXTRACTION, you use various techniques to animate still images. How did you develop these techniques and how has that changed over the course of this project?

Sanaz Sohrabi: I’ve worked a lot with historians and anthropologists through my different research groups that work on oil, and no one knew about this guy [James Menhall whose gravestone opens ONE IMAGE, TWO ACTS]. It took an artist who is obsessed with oil to find this guy’s grave and film it. There is something about visual arts research that is so important in thinking about the history of extraction visually. The history of extraction of oil in the Middle East is very well written—there is a lot of scholarship from anthropology, history of architecture, urban studies—but in all of these scholarships the image always comes secondarily if not at the bottom of the list. To me that grave, in and of itself, was a testament to the peculiarity of this history and its visualization, and the places in which we encounter that history. It was a no-brainer for me to start ONE IMAGE, TWO ACTS with that history. It was the thesis of the film; it was a point of departure to talk about certain moments being highly visible and visualized.

A part of the project is to think about how, through these forms of artistic research, we bring an embodied way of unpacking images and commenting on images with images. Creating a visual dialogue with images—after Harun Farocki and that tradition of thinking about image as a method—is key to the project.

The other thing that is interesting is when we think about the indexicality of images, and indexical media and its relationship to extraction. Film and photography have a specific relationship to extraction of oil, especially cinema. Cinema and the extraction of oil on an industrial scale overlap in a critical way that makes us rethink the history of cinema globally but also in a specific context—the history of cinema in Iran. It has to be re-considered, re-narrativized, and re-read from the perspective of petro-modernity’s influence and media infrastructure that changed the relationship to cinema in the country.

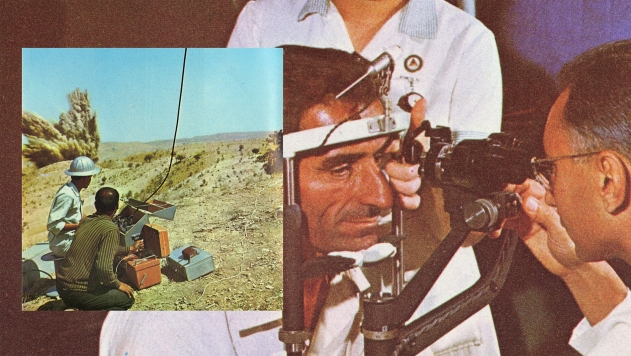

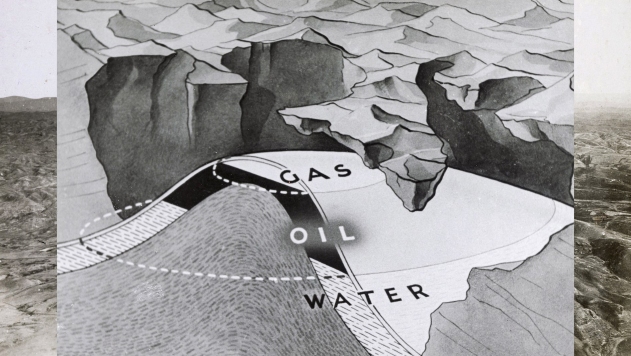

© Sanaz Sohrabi / VOX, Center for Contemporary Images, Montréal. Images reproduced with the permission of BP p.l.c.

S&F: Can you speak a little more about how you read images of oil in the archives you’re working with?

SS: When you see how much the transnational oil corporations, foreign and national governments, and political actors have used what it means to visualize oil for political and ideological reasons, we arrive at a form of indexicality where, when you look at a swimming pool, you think about oil, or if you look at a social club, or cinema space, you think of oil. Oil does not necessarily need to be present in the frame; it’s connected by its social and cultural specters inside the frame. The possibility of opening that notion of the indexicality of oil worked really well in the space between the still image and the moving image. How can I animate and unpack a still image and make it into a moving image?

Tina Campt wrote this book Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europeand a well-known book Listening to Images, which is a method for this project—how can we listen to these images? How can we sound these images? What do they sound like? She has this notion of “still-moving-images” as one word, and that is really a methodology for me. And Harun Farocki, using images to comment on images, that has been present in both of my films. Extractivism has wrestled with the visual field to make itself visible and invisible, and it’s very political.

© Sanaz Sohrabi / VOX, Center for Contemporary Images, Montréal. Images reproduced with the permission of BP p.l.c.

S&F: At what point did you arrive at the trajectory of these three films? What’s your plan for the last one?

SS: The third one, which I think will be a short feature, is about the history of OPEC. When these oil-producing countries from the global south came together and formed OPEC—the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries—in 1960, it was a way to have sovereignty over the pricing of oil. The film looks at their ways of internalizing extraction, meaning how they wanted to differentiate themselves from their colonial predecessors, and also make their oil uniquely national. At the same time, they formed this transnational solidarity around oil with other oil-producing countries. Here we have another way that the indexicality of oil becomes at the same time national and transnational.

This third film is also very archival, it has a lot of newsreel footage and a lot of stamps. I have been collecting stamps for six years and have probably the largest oil stamp archive that anyone can have—boxes and boxes. I’ll be looking at the history of OPEC in relation to the non-aligned movement, to the competing projects of some of the OPEC members in relation to Palestine, in relation to forming solidarity around oil.

The first film, ONE IMAGE, TWO ACTS, was really thinking about film history at the intersection of oil; the second one is about science-technology studies and media archology at the intersection of oil; the third one is really about the politics of solidarity at the intersection of oil. These were the three main issues that I became fascinated with, that were visually captivating and understudied and under-analyzed. The field of the visual was completely untouched when it came to OPEC, STS [science-technology studies], and the history of photography in relation to extraction.

♦

TOPICS