Inspired visual effects tell the true story of NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity—“Oppy”—who embarked on a 90-day mission to Mars in 2004 only to last years. Ryan White’s documentary GOOD NIGHT OPPY recreates their mission, including interviews with the passionate scientists who kept contact with the rovers for so long. The film will screen at Museum of the Moving Image on November 16 in advance of its premiere on Amazon Prime on November 23. We sat down with White at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) where GOOD NIGHT OPPY made its international premiere.

Science & Film: What techniques did you use to bring the rovers to life?

Ryan White: Visual effects are a huge part of that because otherwise you would never see the robots—that selfie at the end reminds you that the people [at NASA] had never seen the robots. This little black and white image was all they ever got. The idea for the visual effects came together on the first night this project was hatched with Film 45 and Amblin. They met with me about making the film. You can’t not fall in love with the logline: a robot that was supposed to live for 90 days ended up surviving for 15 years. That’s how they pitched it to me, and I was like, sold! It was that night where I was like, can we do big-time visual effects? Can we find a way to put the audience on Mars? We had all the imagery, telemetry, and metadata from the orbiters in the sky above the rovers.

It was such a unique opportunity to make a documentary, fully steeped in authentic imagery, to bring that to life in a real way where the audience could feel like they were on Mars. Industrial Light & Magic, who did the visual effects, savored the opportunity to create a real Mars. Mars films are generally an actor in a desert in Utah. Here, they were creating it completely from scratch with real imagery.

As far as anthropomorphizing the robots, we tried never to do it ourselves. All my creative collaborators—DPs, editors, sound designers–we were constantly challenging each other about, are we anthropomorphizing the robot here or are we allowing the humans that are telling the story to do so?

S&F: Why was it important to you to stay away from anthropomorphizing the robots yourself?

RW: Because we were making a documentary. It’s such a great story, it sounds like science fiction or fantasy. My favorite movie growing up was E.T. so to get pitched a story with that tone and trajectory—a non-human you’re going to fall in love with and you’re going to have to say goodbye to at the end, it’s going to be very sad but also very hopeful—was such a rare opportunity for me as a doc filmmaker. Also, to be able to have people of all ages watch it. I’ve made many documentaries that I love but a kid could never watch them, they’re so dark. This was one where the little me would have been able to watch it.

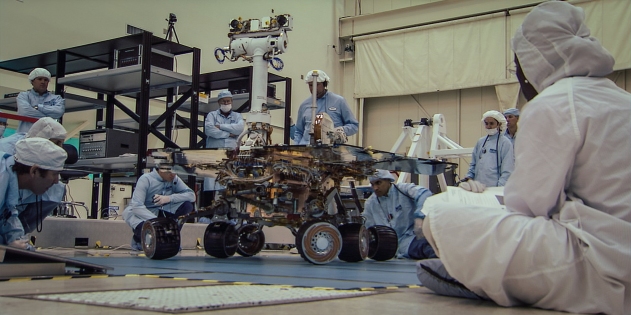

Still from GOOD NIGHT OPPY, courtesy of Amazon Studios

The idea was, we’re not making sci-fi, we’re making a doc, but we have an opportunity to do something on a scale we don’t normally get to do. We have incredible partners like Amblin, Industrial Light & Magic, and sound designers Mark Mangini who did DUNE and just won the Oscar, but he’d also done MAD MAX FURY ROAD—he’s like the best in the business, but he is also very steeped in reality and he does not like to take liberties. He was at JPL with dozens of microphones on the copies of the robots. They booted those robots up for the first time in a decade for Mark and he had microphones all over recording what all the parts sound like. So, those are synthetic sound effects. Same with the ambient sound of Mars. Opportunity and Spirit did not record sound, but Perseverance, the new rover, does, so she was sending sound back as we were finishing the film. It was the first sound to come off of Mars.

S&F: The film features a number of interviews scientists from the NASA team, and I was surprised when they got so personal. Was that something you felt like you had to coax out of them?

RW: Thousands of people worked on those robots, and I’m sure some of those people are very analytical and unemotional—some of the people in the film are not that emotional. Some of them don’t gender the robots as female, they say “it.” We have 12 people in the film and there are various levels of emotional attachment and anthropomorphizing. How do you pick 12 people to represent all the people who worked on this? That was really tough. We did about 30 pre-interviews with people we knew would be interesting for some reason. My producing partners did those because I don’t like to interview people twice. A lot of the interviews were like five hours long because people were so excited to talk about it. We used all of that research to write the screenplay. Me and Helen Kearns who is my longtime editor, we wrote the screenplay.

S&F: What was the balance you wanted to strike in the film between too little and too much science and technical content?

RW: Big, big debate in the edit room. [Sometimes] we would watch it and be like, this is too dumbed down, we’re not making a children’s film—a child can still enjoy this film without totally understanding the technical details or the science. I was the only producer who didn’t have kids, so everyone was watching the film at their homes and looking at what the 2-year-old or 4-year-old would relate to.

It wasn’t like from the beginning we knew that it’s going to be ‘this much science’ and ‘this much adventure.’ It was tough because I’m used to winging it. You can’t do that with visual effects; you don’t have the liberty of, the month before, to do the doc style “we’re just going to go out and shoot more.” Creating a new shot takes a year. But so much of the science [came from] archival of what the rovers had shot themselves that we were able to figure that part out in the edit room.

NASA didn’t have to design robots that were cute and lovable, it was a conscious decision. They say that at the beginning of the film. The rovers look like WALL-E, they look like SHORT CIRCUIT. NASA knew the taxpayers would fall in love with the creatures they sent up there and then hopefully would be so along for the journey that the science these robots were figuring out on Mars would be digested. So, that’s what the film does: it invites people in for the journey and then the science is incredibly important, and we didn’t want to leave that out. There are some very specific scientific achievements that Spirit and Opportunity had that ended up on the cutting room floor for whatever reason, because we couldn’t make a 2.5-hour film, but I think the basics are there about why their legacy is so important.

Still from GOOD NIGHT OPPY, courtesy of Amazon Studios

S&F: The selfie that the robot takes made me think of the Pale Blue Dot photograph that Carl Sagan pushed for. How do you see the significance of that moment?

RW: [That was when] we became attached. Opportunity died the year before we started making this film. There was an article that came out that had her last communication: my battery is low and it’s getting dark moment. Even if you hadn’t been following the journey, which I had because I’m a space geek, when that article went viral it was a gut punch for people who didn’t even know who she was. So the selfie moment, every person we interviewed talked about how incredibly special it was. It was like the yearbook photo of their child they had sent off to boarding school. Abigail Freyman [from NASA] who was 16 when they launched the robots, she’s one of the most practical people about the robots, even she got so emotional talking about the selfie. It brings something so far away back to Earth. That feeling of: this is infinity but it’s also very close to us I think is what that selfie did.

S&F: Seeing your film will be another way that this mission comes home for the people who worked on it. Have any of the scientists you feature seen the final cut?

RW: Yes, two are here [at TIFF]. We had a screening in Pasadena, about ten minutes from where I live, for all of them. I was nervous. The worst part of documentary filmmaking is showing your film to the subjects for the first time. No matter how great the film is, no matter how much they’re going to love it in the end, it is awkward. I don’t know what that’s like, to watch your life interpreted by someone else and to have to digest it in 90 minutes. But this was probably the least awkward, best reaction I’ve ever gotten, maybe because it’s a team. I made a Serena Williams film and I remember showing her the film in an empty theater and she did not talk after, she looked at me shell-shocked and she got up and walked away. This team was bawling and hugging each other, so there was this camaraderie. A lot of them don’t know each other! There were a lot of hugs and tears when they came out.

♦

TOPICS