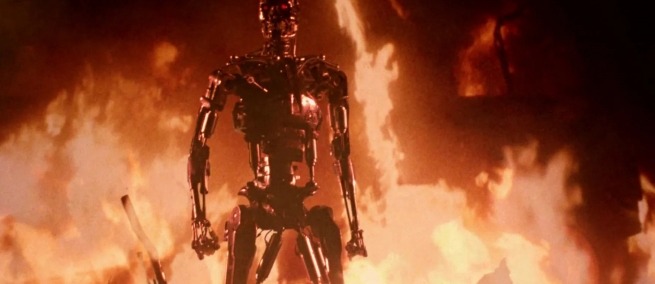

Since James Cameron’s Terminator android (Arnold Schwarzenegger) tracked and murdered human targets in 1984, we’ve seen a real-life, accelerated evolution in artificial intelligence (AI) that could be equally threatening. Technological advances in remote or autonomous surveillance, identification, and delivery of lethal force inspire considerable debate over their uses by law enforcement and by the military, especially in drone warfare.

Much of the debate is about facial recognition AI, which identifies a subject by comparing their face to enormous databases of known faces. Police use it to find criminal suspects by matching their faces to surveillance videos, but in today’s search for social and racial justice, the algorithms are severely criticized. Their accuracy is not subject to any standards, and they are more error-prone for non-Caucasian faces than Caucasian ones. These flaws became real and prominent this year, when an incorrect algorithmic facial identification led Detroit police to falsely arrest an African-American man. He was released only after spending thirty hours in jail and posting a bond.

Correctly identifying a person is essential for equitable policing, and that extends to the even more potentially destructive use of drone warfare, in which the U.S. military finds and kills enemy combatants with armed semi-autonomous drones. These are controlled by remote operators thousands of miles distant, subject to higher authority. Reports indicate that the military may soon add facial recognition to its drones to reduce human error, but given the lacks in the technology, this may only prove a complication.

Sleep Dealer

With or without recognition technology however, the human links in the decision chain are meant to provide oversight and final approval for lethal drone attacks. This has not prevented U. S. drones from killing or injuring at least 200 civilians in Iraq and other war zones in 2019. Recognizing this issue, several filmmakers have recently addressed our current qualms with AI and facial recognition. These films portray people and technology interacting in the use of killer drones.

Director Alex Rivera’s near-future film SLEEP DEALER (2008) follows Memo (Luis Fernando Peña), whose father, a Mexican farmer, is killed by a drone strike for protesting a corporation’s dam, built to sell water for profit. After his father’s death, Memo finds work in Tijuana, “jacking in” to a neural network to remotely build a skyscraper in the U.S. When he meets Rudy, the drone operator who killed his father, they come to an understanding and unite to smash open the dam and free the water for the community. Ultimately though, they cannot destroy the corporation itself. In this intervention, Rudy rises above “just following orders” to act on what he feels is justice.

In Andrew Niccol’s GOOD KILL (2014), another drone operator faces up to his conscience. U. S. Air Force Major Thomas Egan (Ethan Hawke) proficiently kills terrorists in Afghanistan from a drone base in Nevada. But he comes to feel guilty, especially under a CIA manager who finds civilian casualties acceptable. Egan drinks heavily and his marriage suffers. To redeem himself, he simulates a drone malfunction to let civilians on the ground escape, then uses the drone to kill a known rapist who surveillance shows is once again approaching a former victim. The film ends on an unresolved note, showing Egan leaving his post for an unknown fate. Like Rudy, Egan counters orders to use the drone to fulfill his personal choices, but letting his emotions drive him to carry out a summary execution is not a moral response.

EYE IN THE SKY (2015), a thriller directed by Gavin Hood, shows how dependence on drone technology and AI can affect human judgment. British Army Colonel Katherine Powell (Helen Mirren) plans to observe and capture terrorists in Nairobi, Kenya, using drones controlled from the U. S. When a facial recognition algorithm identifies suicide bomber terrorists who could kill civilians, she changes the drone’s goal to “kill.” Besides her complete trust in the AI identification, this is legally and morally questionable: the U.K. and U.S. are not at war with Kenya, and a drone strike could harm a nearby young girl. Zealous to gain government approval for lethal action, Powell deceitfully reports the odds of killing the girl as below 50%. After authorization by the U. S. Secretary of State, the drone operator fires missiles that kill the terrorists but introduce moral ambiguity by also killing the girl.

Good Kill

Good Kill

Overall, these three films show that human choices can sometimes properly modify or override technological decisions. In two dystopian works that anticipate the future of machine killing, the human element is removed, with bleak results.

The short film SLAUGHTERBOTS (2017) begins with a man on stage before a live audience. He looks like a tech company executive but he is selling a weapon: a palm-sized, autonomous drone armed with facial recognition AI and an explosive charge to efficiently find and kill a victim. With fictional news clips and interviews of distraught people, the film imagines how chaos could result from unstoppable swarms of the drones. SLAUGHTERBOTS is effectively a call to action from the Future of Life Institute, which aims to reduce threats to humanity from AI. The film’s dramatic tone highlights the dangers of autonomous weapons in large quantities.

How close are we to facing the horrors of the autonomous drones in SLAUGHTERBOTS? Not very close. The armed U.S. military Reaper drones are big, long-range units, with a wingspan of up to 79 feet. SLAUGHTERBOTS has inspired discussions that explain how far off we are from creating the necessary AI and cramming it into tiny drones along with an explosive charge and extended flight capability.

Made the same year as SLAUGHTERBOTS, the BLACK MIRROR episode METALHEAD (2017) imagines the dangers of autonomous technology differently. In an undefined future, Bella (Maxine Peak) and two male companions break into a huge warehouse, searching for something until their movements awaken a watchdog-like robot with an unnervingly featureless head. It shoots small devices into the intruders to tag them, brutally kills the men, then follows Bella as she flees through open country and into a vacant house. The robot dog is fast, strong, and smart, but Bella uses her human skills and fortitude to painfully cut the embedded tags from her flesh, then disables the dog with shotgun blasts. Still, she and humanity do not really win. In its last gasp, the dog shoots more tracking devices into Bella. The final scene shows her with knife in hand, hopeless and ready to slit her throat as more robot dogs converge on the house. The episode hints that the dogs have already hunted down most living things, leading a viewer to speculate that they are killer robots left over from a previous war.

Metalhead

Metalhead

As an entry to the world of METALHEAD, we already have ground-based robots with substantial physical abilities. The dog in METALHEAD resembles actual robots created by the company Boston Dynamics, although battery capacity limits their potential. However, to chase Bella, the dog had to perform high-level cognition such as navigating complex environments and spontaneously deciding to use a kitchen knife as a weapon. Today, AI performs some tasks better than people, but generalized AI does not yet match the cognitive abilities of a real dog or person.

The errors and biases in facial recognition are good reasons to be wary of it and other AI being applied in warfare. But whatever the intelligence of future self-guided weapons, they would be relentless like the Terminator which, as described in the 1984 film, “can't be bargained with. It can't be reasoned with. It doesn't feel pity, or remorse, or fear!” For all their flaws, people in the decision chain feel those emotions, and therefore remain necessary to keep warfare by algorithm from becoming an inhuman nightmare. ♦

TOPICS