Contrary to popular thought, the first laser light show was not set to Pink Floyd, nor other psychedelic rock music that helped make the laser light show so popular with youth in the 1970s, hanging out in dark planetariums. In fact, the original show was set to classical music, “Fanfare for The Common Man” by Aaron Copland, and originated by a scientist—Elsa Garmire. Garmire’s contribution to the arts began in association with the legendary organization Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Filmmaker Ivan Dryer had the idea to bring the laser light show to planetariums. The first laser light show was held in 1973 at the Griffith Observatory and Planetarium in Los Angeles. Dryer made a proof of concept video of Garmire’s laser images in 1972, called LASERIMAGE, which has just been preserved on 16mm.

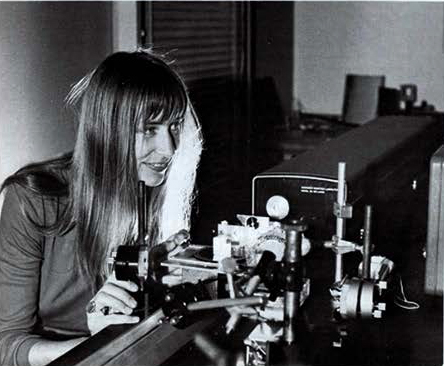

Elsa Garmire

The mission of the organization E.A.T., which was co-founded by artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman with engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer, was to pair artists and engineers to realize new work that could not be realized otherwise, and might influence future technical developments. Elsa Garmire embodies this mission; she used her training as a physicist and engineer to create new artworks. These works influenced projection technology, and had an immeasurable cultural impact on making science museums a destination for the public.

Garmire, recently retired, has made significant contributions to the field of optics; she was Professor at Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering for 21 years including holding the Deanship, was at USC for 20 years before that where she was Director of the Center for Laser Studies, is past President of the Optical Society of America, and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering at a time when there were only 20 female but 2,500 male members.

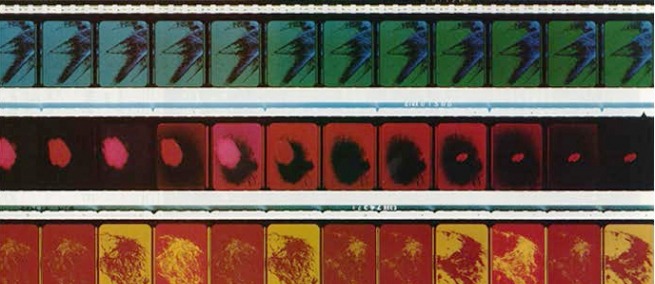

Still from Laserimage

Laser is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation—one band of the color spectrum is amplified by a machine. Laser light has a special property called “coherence” which means that all of the particles of light move in the same direction in the same way because of the nature of the stimulation. This gives the light a special shimmering quality. Garmire became interested in lasers while completing her doctorate in physics at MIT; Nobel Prize-winning physicist Charles Townes, who developed the concept of the laser, was her thesis advisor. She wrote her thesis on the second commercially sold ruby laser, which could create light focused enough to penetrate a razor blade. Garmire went to Caltech for her post doctoral work where she was supervised by optical engineer Amnon Yariv, who had worked at Bell Laboratories and was friends E.A.T. co-founder Billy Klüver, who also worked there. Garmire started a research position with Yariv in 1966. Two years later, Klüver reached out to Yariv for a recommendation for someone to help on a new project.

In 1968, E.A.T. was asked to design the Pepsi Pavilion for the 1970 World’s Fair in Japan, called Expo ’70. Yariv suggested that Garmire participate. “He knew I was an odd person, I guess. I’m not sure I had been involved in art before then, but the professor knew me pretty well and thought I would find it interesting, and I did,” Garmire told Science & Film over the phone on June 11, 2018. Working alongside artists such as Lowell Cross, Frosty Myers, Robert Whitman, David Tudor, Fujiko Nakaya, Robert Breer, and over 50 additional scientists and artists, Garmire’s purview on the Pepsi Pavilion project was within a reflective dome that spanned 90 feet. The dome had two floors; the lower level was lit by moving laser lights emanating in four colors from a krypton laser to project X-Y scanned images, a laser light show designed by Lowell Cross. Upstairs, the dome was covered by a spherical reflective mirror and had a specialized sound system with 37 speakers installed throughout. According to The Story of E.A.T. that Billy Klüver published in 2001, Garmire was responsible for calculating the properties of mirrors in the room, and also helped build a model to test the optical effects.

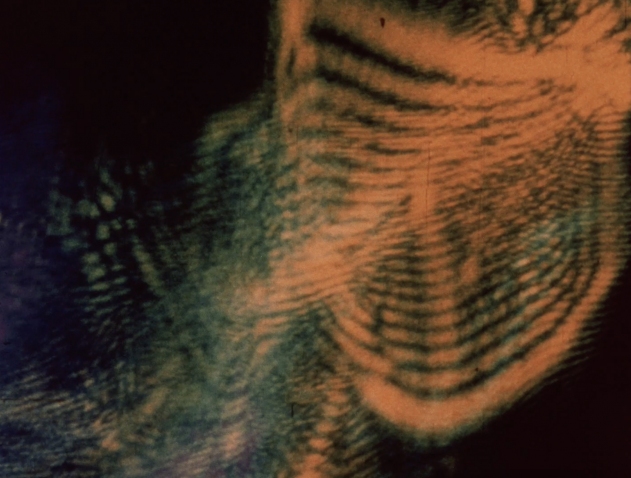

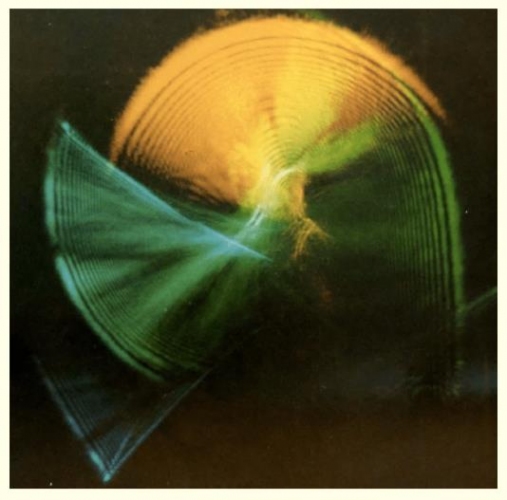

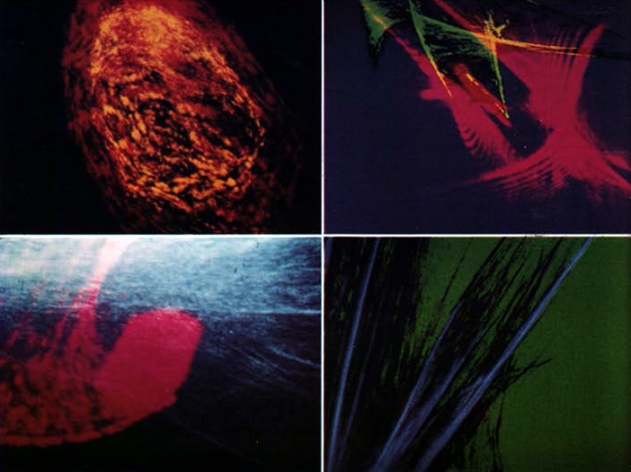

A laser image by Elsa Garmire, 1970s, courtesy Dr. Garmire

Elsa Garmire did not like the laser light show in the Pepsi Pavilion. “There was a standard way of putting X-Y mirrors on the laser and getting what us scientist’s call Lissajous figures, which are sort of ovals. You can get lots of ovals of different sizes, moving in different directions, and you can run them with music and get a kind of wild pattern that to me has no aesthetic value at all,” she told Science & Film. What was impressive about the installation, according to Garmire, was that the image seemed to be moving toward the observer, as an invitation for them to enter the space. It was 1970, and Garmire started asking herself how lasers could make good art. She continued, “I decided the only characteristic of lasers was that they were pretty, so I developed this way of making these laser images as photographs, and I convinced a woman, who was starting a new photography art gallery [called Photosphere in Hollywood], that she should show my prints for the opening of her gallery and that it would get press. And it did, it got television press.” In addition to her photographs, Garmire created an installation of a small laser light show in the exhibit. This was the start of the iconic laser light show. “My plan was to sell [the laser light show] as a thing that you put on in your home, with the simplest laser you could get which in those days was the helium neon laser with a cost of $600, probably about $2,000 today. I found no one willing to buy one and I was very sad because I thought it was fantastic. But anyway, I got a lot of publicity and out of it these couple of kids from UCLA’s film school called me up and said they wanted to see it,” said Garmire. Ivan Dryer—now credited as originating the laser light show industry—and Dale Pelton—who would become one of the co-founders of the laser light show production company—went to Caltech to meet Elsa Garmire and registered laser-generated images on celluloid for the first time.

At Caltech, Dryer filmed laser images that Garmire created. The sculptural shapes dance in and out of the black background. They flash as rock music comes on, dissolve and cross-fade to classical music, appear in colors from light blue to bright red in different textures moving at varied speeds. LASERIMAGE, made in 1972, was a proof of concept for producing a full-scale laser light show set to music and run by an individual (rather than automated). Dryer had been working as a tour guide at the Griffith Observatory and Planetarium and had the idea to pitch the laser light show there. Together, he and Garmire formed the company Laser Images Inc., which would become responsible for producing the light shows. Laserium (“house of laser”) debuted its one-hour light show at Griffith Observatory and Planetarium in November 1973, and it became the longest-running theatrical attraction in Los Angeles—on view from 1973 until 2002.

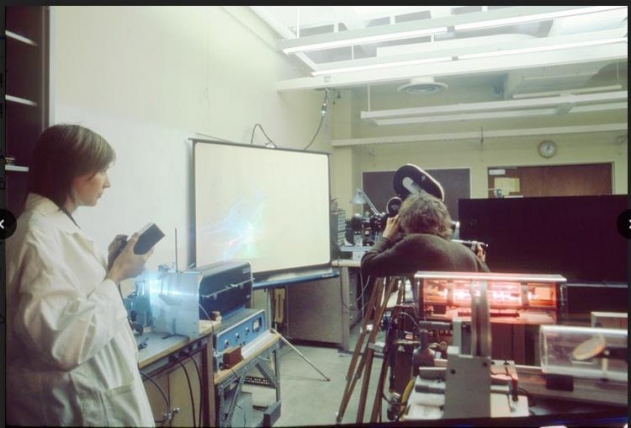

Elsa Garmire running lasers and Dale Pelton filming at Caltech, by Ivan Dryer, courtesy Dr. Garmire

After meeting Dryer and Pelton and developing the concept for a laser light show, Garmire was asked to give a Beckman Lecture—a significant ask—at Caltech. “I set up a laser light show there just like we used in Laserium and explained how it worked,” she said. Not only was she a postdoc giving this prestigious lecture, but “today they never would have let me do that because there were no laws yet about sending lasers around rooms. Being an expert, I made sure the lasers weren’t going to hit anybody’s eyes so it was perfectly safe, but the government would have been appalled.” Her lecture on laser art garnered such interest that the student newspaper The California Tech (28 January 1971), reported 500 people were turned away. Laser art, the paper wrote optimistically, “is more spectacular and less artistic than other art forms and its use is limited by many factors. But it should come up with some surprises in the future.”

In 1973, Garmire, Dryer, and Pelton made a second film starring lasers. DEATH OF THE RED PLANET was a monocolor film in red. “The constantly evolving forms sometimes appeared as living tissue and, at other times, like creatures found in some distant unknown part of the universe,” Pelton wrote in the July 1973 edition of American Cinematographer, about seeing Garmire’s laser demonstration. He continues, “I became more aware of the strife implicit in these kinetic forms. Much like the process of life where opposing forces are operative in creating new life forms, I decided that the film would be about this conflict, a cosmic struggle between the forces of blue and the forces of red. In the manner of absurd 1950 science fiction flicks, I entitled the film DEATH OF THE RED PLANET.”

Garmire is the founding president of Laser Images, Inc, which presents the Laserium show, but she ultimately pursued science as a career. She handed the company over to Ivan Dryer, who continued with it until his death in 2017. “Laser images are absolutely gorgeous, I still think so to this day,” Garmire said to Science & Film. “They just really turn me on. They’re so organic. I still think it was and could be a very successful way to give background to music.”

Images from DEATH OF THE RED PLANET, American Cinematographer, July 1973

Recorded laser images have hardly been seen by audiences, which is one reason why this restored print of LASERIMAGE is so special. Lasers are typically an unappreciated utility in daily life: laser pointers in the classroom, laser printers in the office, CD or DVD players occasionally used. Lasers in live shows, of the kind that Garmire envisioned, have cultivated an audience of laser art appreciators.

A digital copy of LASERIMAGE, produced from the original negative, is specially available to view here on Science & Film, courtesy of the Exploratorium in San Francisco. LASERIMAGE was preserved in 2018 by BB Optics with a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation, and was presented at the Museum of the Moving Image during the 2018 Orphan Film Symposium.

For more on Laserium, look out for a documentary called GODS OF LIGHT, directed Bjorn Schaller, which is currently in the final stages of post-production.

TOPICS