Technological developments such as the computer–which was improved upon in order to develop the hydrogen bomb–have often been spearheaded by the military. This includes film. Nitrocellulose, otherwise known as guncotton, was used in warheads and as explosives. Guncotton became nitrate film once the chemical compound camphor was added, turning the guncotton into a flexible plastic. Films were shot on nitrate until the 1950s. Filmmaker and artist Bill Morrison has worked with nitrate film for most of his career. His early work “swims in the roiling emulsion of the nitrate,” he told Science & Film on the phone. Morrison does not shoot on nitrate, which has been banned since 1951 when acetate-based safety film was invented, but uses found footage.

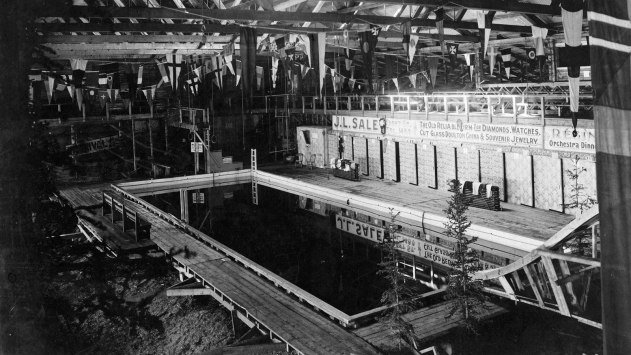

Bill Morrison’s new documentary, DAWSON CITY: FROZEN TIME, is collaged from a collection of 533 silent nitrate films to tell the story of those very films, which were uncovered in 1978 in the northwest Canadian town Dawson City. The town was colonized during the Klondike Gold Rush and then turned into a tourist destination; nitrate films were projected at its movie theatre. Once the films were shown, the city was encouraged by distributors to destroy the film reels instead of shipping them all the way back to the United States. Rather, the films ended up in a landfill underneath a hockey rink. Inadvertently preserved, they have become a record of early twentieth century film and are now at the Library of Congress and the Library and Archives Canada. The Dawson City films can often be identified by white streaking, known as the Dawson Flutter–the result of water damage.

“Nitrate famously explodes and catches on fire,” Morrison told Science & Film. “But it infamously melds together over time. That is a process whereby the camphor exits the base and it leaves a brittle and increasingly solid mass behind that you cannot unspool. In various stages of decomposition it gets sticky and then solid, and it is called a donut or hockey puck once it has reached that final stage. Eventually it’ll turn to powder.” Morrison has a working relationship with the Nitrate Film Vault Manager at the Library of Congress’ audiovisual preservation center, George Willeman, who keeps an eye out for films Morrison may be able to use. Morrison travels there at least once a year. “What I try to do is go down there and find interesting examples where the nitrate has interacted with the image in a way that I find compelling,” he said. “I also work closely with a lab in Maryland called Colorlab and they’ve developed a process for working with the material I bring them where they soak it in water, unspool it, and eventually scan it. It’s really through the collaboration of these institutions that I have had access to nitrate.”

After the Dawson City films were found, preservation copies on safety film were made. Many of the films Morrison uses in DAWSON CITY: FROZEN TIME were scans of those preservation copies, but “in some cases, especially where you saw color, we were scanning directly off of nitrate. The example that would come to mind most quickly would be that hand-colored, hand-painted sequence from TRAIL OF ’98 where [Dolores del Rio] is holding gold in her hand, and golden mountains are off on the horizon.”

Nitrate films have a crisp image quality before they decompose. This can be attributed to the fact that filmmakers in the early 20th century “often struck prints off of the camera originals so that instead of having successive generations like you would have later in the century, when there would be an internegative or copies made from an internegative, all of the distribution prints would come off of a master camera original. There also was quite a bit of silver in the emulsion in those days that would make richer blacks. Nitrate was more transparent than the acetate base so that would make lighter whites.”

DAWSON CITY: FROZEN TIME, distributed by Kino Lorber, is playing in New York and Los Angeles. Morrison’s other feature-length films include DECASIA, the first film of the 21st century preserved by the National Film Registry. For more on nitrate, read Science & Film’s report from the annual Nitrate Picture Show at the George Eastman Museum.