Owen Bell is designing a digital game about Mendelian genetics. Gregor Mendel was a scientist working in the mid-nineteenth century who cross-pollinated pea plants selecting for certain traits such as height and color. These traits ended up being the expression of genes.

A graduate of NYU’s Game Center, Bell received a $10,000 Sloan production grant to develop and launch MENDEL. He is the first person to ever receive a Sloan grant for a game. Science & Film spoke with him from his home office in New York after he found out that he had won.

Science & Film: Why were you interested in making a science-related game?

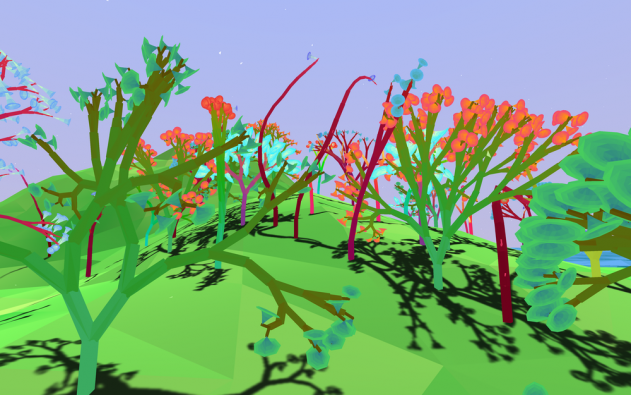

Owen Bell: The idea has been kicking around in my head for a few years. I ultimately decided to make it for my MFA thesis. Originally, it started as a project about growing plants. I joke that it is a game made by someone who likes gardens, but doesn’t like gardening; you can breed plants without worrying about weeding or watering them. The game is focused on the creative process of breeding, and trying to select for particular traits that you like.

One of my backgrounds is in computer science and I get very annoyed when writers of television and movies get the science wrong. I wanted to honor the science of genetics. It was through the process of learning about genetics that the game evolved. Now it’s not just a game about breeding but also a way of expressing how interesting this science is.

S&F: Did you work with a geneticist?

OB: I worked with Dr. Eric Brenner who is a genetics professor in the Biology Department at NYU. With him, I talked over what I was doing and how I was implementing my research. He made sure I was representing the science in an accurate way.

S&F: At what point did you learn about the Sloan grant?

OB: The grant was mentioned to me by my department fairly early in the process. Me and a couple other people in the game department applied. When I was applying, I didn’t realize that I was applying for the first grant to a student game designer. I only realized what I had applied for after I won.

S&F: Why do you think there have been so few games about scientific topics?

OB: I think historically in games there has been a certain prejudice from game designers making entertainment games towards designers making educational games; they say that the educational designers do not integrate the entertainment part. That is an opinion I do not agree with at all. Game designers have not looked to foundations like Sloan that are interested in promoting understanding of different topics through game play. But just in the past couple of years, there has been an explosion of games particularly about genetics. I think that is because we have seen so much in the news about technologies like CRISPR, so it is in the zeitgeist right now.

S&F: What sorts of games did you use for reference? I loved farming games like HARVEST MOON when I was young.

OB: I didn’t really look at games that are explicitly about farming, like HARVEST MOON. I was looking at other games such as MINECRAFT that were developed for entertainment but now occupy a very viable niche in education as well.

I want players in MENDEL to actually engage in the scientific process. They will be creating their own scientific experiments and figuring out what they wanted to look for and how to isolate traits without being specifically directed by the game. The game is never telling you: find a flower with these exact traits, or mix these things together and see what you get. Instead, it is up to the player to figure out what they want to do on their own, and hopefully, by doing some experiments, figure out how to do that.

S&F: Is there a name for that kind of game play?

OB: Sandbox game is the most common term. It describes an open-ended experience where the player is left to their own devices to make things, rather than given a specific direction.

S&F: What’s next for MENDEL?

OB: The goal right now is to release the game towards the end of 2016. It would be available for digital download both through the game’s blog and through PC and Mac digital platforms.

S&F: What more do you want to add to the game?

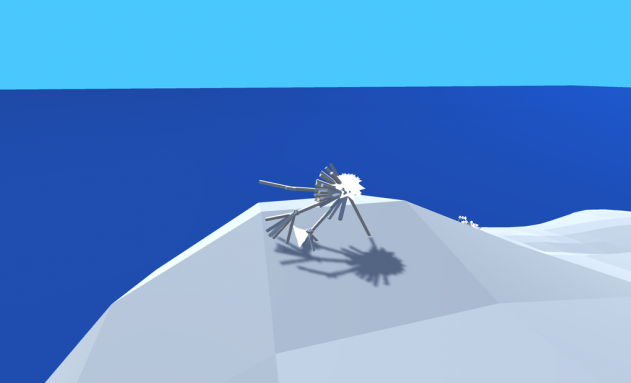

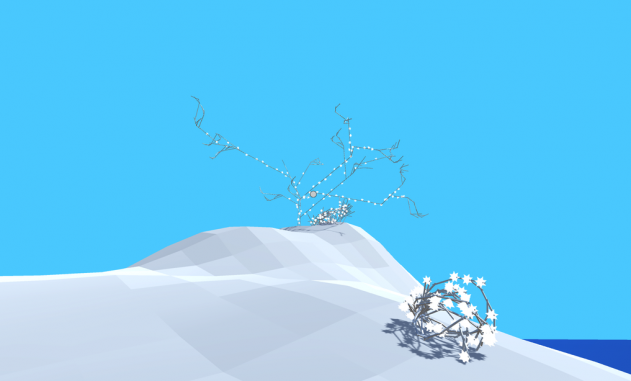

OB: One of the things that is a constant challenge with this game is how players of all ages, though particularly those in their 20s or older, find out that they don’t really understand genetics when they sit down with the game. One plant trait you see in our real world is a flower with stunted branches. That was something I implemented in the game. This is just a single gene and when it’s in a dominant state your flower has branches like normal and suddenly it gets suppressed and the flower looks radically different. This is a single change in genetics, but when players see it they are completely floored and they start insisting that the game has got the genetic model wrong. So, there is a lot of experimenting I’m doing with figuring out what is the best way to convey this information to people. Should I just leave them on their own to figure it out? Do I give them a more specific breakdown of what the gene looks like? Should I give them a family tree so they can look at where this family of genes is coming from? I am experimenting with how to frame this experience so players have the tools to best understand what they are doing without explicitly sitting the player down and saying, let me teach you something.

S&F: Do you use test groups?

OB: I have done a number of things. My program at the NYU Game Center hosts an event on Thursdays where anyone from the public can come to our space to test games. Also, I try to go to various events. Recently, I was in Boston for the Boston Festival of Indie Games and I probably showed the game to at least 100 people over the course of the day. There, you get a huge density of response and lots of different ideas from people young and old.

S&F: Do you have a target demographic?

OB: I am aiming to make MENDEL for as broad an audience as possible. One of the core conceits of the game is that the play is very simple. At a most basic level, all you do is take two samples, either from a single plant or two different plants, and mix them together in the ground. I want that to be as engaging an experience as possible, so that even if you aren’t interested in the genetics or experimentation that process is very satisfying. It is interesting how something that simple engages people. That part of the game is quite effective across all different ages.

Owen Bell’s blog documents the development of MENDEL. He hopes to release the game at the end of 2016. Check back on Science & Film to download and play.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS