The Whitney Museum of American Art has a new group exhibition, Dreamlands, opening at the end of October about the history of immersive cinema. From beanbag chairs, to a room covered in black velvet, to a floor strewn with oranges for a multisensory experience, the show covers 18,000 square feet and seems likely to be one of the most innovative museum exhibitions ever curated and exhibited. The curator, Chrissie Iles, has co-curated two Whitney Biennials, and the first survey exhibition of historical film and video installation in America.

In Dreamlands, Iles places contemporary artists in the context of historical experiments with the medium. Two of the contemporary artists, Frances Bodomo and Lynn Hershman Leeson, are Sloan Foundation grantees. Bodomo received support for her 2014 short film AFRONAUTS which is being turned into a feature, and Leeson for her 2002 feature TEKNOLUST. Science & Film spoke with curator Chrissie Iles in a glass paneled conference room at the Whitney Museum on July 6, 2016.

Science & Film: In researching a show that is a chronicle of motion pictures which spans 1905 to 2016, are movies are dead?

Chrissie Iles: I don’t think movies are dead. Whenever I make an exhibition it is because there feels an urgent need to do so. In this case, I was responding to a sea change that has clearly been occurring in the moving image, and its presence in digital, immersive space. Artists and filmmakers are articulating something dramatically new, using new developments in technology, from virtual reality and 360 degree cameras to 3D and the way in which 3D printing is changing our understanding of material objects. This is profoundly shifting the relationship between technology and the human body, and science fiction, which always operates as a bridge between the present and the future, has become newly important. I spent a lot of time listening to young artists and looking at their work, and it became clear that certain moments in art and film history grappled with similar ideas that have a strong relationship to what is going on now. It became evident to me that the kinds of issues that are being explored now by artists were present in the culture of Weimar Germany in the 1920s. In contrast to France, where experiments with the cinematic were shaped by a dialogue with Surrealism and literature, in Germany, artists were influenced by the Bauhaus and the new industrialized environment, and their work engaged with abstraction, color, light, the cyborg, and technology’s relationship to the body in the spectacular immersive space of the city.

Germany at that point was the most industrialized country in Europe, and the closest to the United States in its urban modernity. The experimentation with abstract film by German artists was also connected to the avant-garde ideas that had emerged during the Russian Revolution. [Kazimir] Malevich attempted to make a film in collaboration with [Hans] Richter, but for various practical and political reasons, it was not realized. In Berlin, artists were exploring the limits of the film frame and optical perception, the impact of technology on the body, using rhythm, mechanical movement, and robotic forms, in film, theater, and also in collage, in the work of artists like Hannah Hoch. The aftermath of the First World War was significant; it had been the first modern war fought with technology, and in every city, including Berlin, was populated by its returning soldiers’ visibly traumatized, wounded bodies, held together with crudely made prosthetics. Bertolt Brecht, Erwin Piscator, and Bauhaus artists were experimenting with new ideas of theatrical space, defined through color, light and fluid architectural structures, creating new possibilities for an all-surrounding immersive projective space. The 1960s saw a resurfacing of this creative energy shut down by the Second World War. It was filtered through a collective processing of the war’s traumatic aftermath–a process intensified by the new traumas of the Vietnam War and the social and political upheavals of that period.

It seems to me that this current new generation of artists is moving that creative energy forward yet again, in a new way that, thanks to the recent radical developments in technology, has made a definitive break with the twentieth century. As a result, their creative approach is focused on the future in a way that resonates with the period of Weimar Berlin. This exhibition brings young artists into a dialogue with that history in a way that is new; their work is more often seen in the context of group surveys, and biennial and triennial exhibitions. The show also shifts the small group of works from the 1960s and 1970s, including Anthony McCall, Stan VanDerBeek, Jud Yalkut, and Bruce Conner, beyond their specific historical moment of expanded cinema, destruction in art, and Structuralist film, into a broader history of art and film.

S&F: And in relation to the technology the filmmakers use too, right?

CI: Yes. Their work can be understood here as part of a broader relationship to technology than simply that of the film apparatus. In making the connection between these different moments in art and film history, I decided to look at the whole century, and tease out some of the main strands that are present in the different decades, which seemed to pivot around immersive space and the relationship of technology to the body. The result is a group of immersive works that use the cinematic in different forms to explore ideas in ways that speak to each other across history.

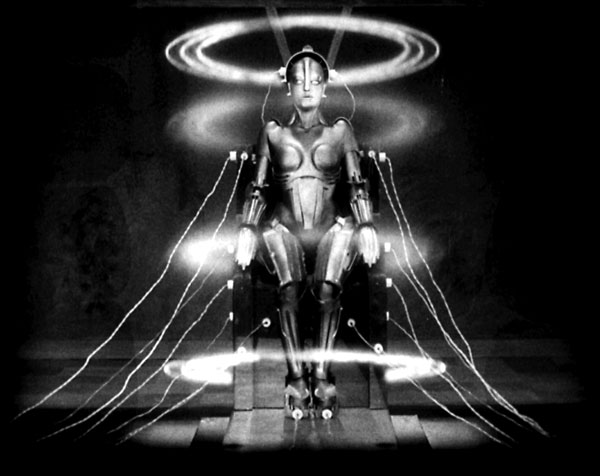

One of the strands of the show is the cyborg and the cyborgian body, which first appeared in the work of artists such as Oskar Schlemmer. The first work in the show is a film reconstructing his THE TRIADIC BALLET from 1922, which was made in the 1960s in Germany. In that faithful reconstruction, you can really see the importance of the robotic body and the First World War (in which Schlemmer took part). The film sets the tone of the exhibition; color, light, music, an animation of line, the flattening of space, the body; immersion. Almost every piece of music in this show is non-diagetic, which underlines the emphasis on affect rather than narrative.

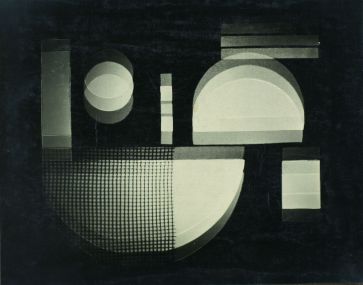

Schlemmer’s colorful work is closely followed by the equally colorful triple screen hand-colored abstract film RAUMLICHTKUNST, by Oskar Fischinger, from 1926, which was made using techniques including printed woodblocks, melted wax, and tinted liquid patterns. The show also includes Joseph Cornell’s film ROSE HOBART, in which Cornell cuts up a print of the 1931 Hollywood film EAST OF BORNEO and reassembles it so that the actress, Rose Hobart, occupies the frame most of the time. He screened the film through a blue glass filter, bathing the actress in blue light.

S&F: Are all the films you are showing digital projections?

CI: No; Mathias Poledna’s film loop is 35mm, and Anthony McCall, Jenny Perlin and Jud Yalkut’s films are shown on 16mm film. We are also showing 16mm, 35mm and Super-8 film in the screening program, alongside digital video.

S&F: It looks like you're interested in immersive space in this show.

CI: As Tom Gunning argues, early cinema was about affect and simple actions, rather than narrative stories. Viewers were immersed in sequences hand-tinted with color, and music. Anthony McCall’s film LINE DESCRIBING A CONE places the viewer in the space of the projection, watching a large white circle slowly being drawn against a black background, the beam of light articulated by a fog machine, to form a large cone of light that people walk through and inside. The work brings together animation with the conceptual, the phantasmagoric and the performative, placing us inside the film itself.

As you walk through the beginning of the show, you will see Bruce Conner’s film CROSSROADS in the distance – a collage of film footage of the Bikini Atoll atomic tests, shot by the American government in 1946, which Conner slowed down and added sound to, including music specially written by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley. The atomic explosions appear again and again, in a slow-motion spectacle, immersing us in a kind of terrifying beauty.

Conner’s film addresses a terrifying moment in both American and world history, in the aftermath of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, showing the power of technology’s potentially destructive force, which Walt Disney’s FANTASIA also addresses--concept artwork for the creation of the world, and the Sorcerer’s Apprentice section of the film, are shown nearby. In Jud Yalkut’s film installation ‘Destruct Film’ (1967) nearby, the floor is strewn with celluloid film, which you walk into, ankle deep, as a film, and stills extracted from it and spun around the room using beam splitters, are projected onto the walls. The installation, responding to the Destruction in Art activities in London and New York during that time, feels as though Yalkut is staging the death of cinema. Film reels are pulled apart and scattered all over the floor. You can lie in it, twist it around your body, mover around with it– but you can’t sit and watch a film in any kind of stable cinematic space. Instead, you literally become immersed in an environment that collapses film into itself.

Along with the concept artwork for FANTASIA, there will be screenings of the film itself during the show. The film is synaesthetic: it surrounds the audience with sound, color, light, and animations which illustrate the music, rather than the other way round. This will be a rare opportunity to see FANTASIA on the big screen.

It is interesting to trace the different ways in which the cyborgian body appears throughout the exhibition. Sometimes the cyborg is female, articulating the fear of the female body through its embodiment as a technological force that has to be brought under control. Some works explore the boundary between technology, the body, identity, and mortality – a classic trope of science fiction. The cyborg appears in FANTASIA, CROSSROADS, and Fritz Lang’s METROPOLIS, as well as in recent artworks by artists such as Dora Budor, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Ian Cheng, and Ivana Basic, as well as Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno’s NO GHOST JUST A SHELL project. All the AnnLee videos from that project will be shown together in one gallery. The show also includes Stan VanDerBeek’s MOVIE MURAL (1971), a collage of movie screens with still and moving images projected onto the walls of the gallery, including cyborgian figures, creating an immersive projected space.

The more recent part of the show begins with Mathias Poledna’s film installation ‘Imitation of Life’ (2013), a three minute 35mm film loop with which he represented Austria in the 2013 Venice Biennale. He commissioned retired Hollywood animators to make the film, creating a short animation that is not a commercial Hollywood production, yet has all its qualities, and the same sensibility. The key protagonist is a donkey in a sailor suit singing Got a Feeling You’re Foolin’, which is a song from a 1930s Hollywood musical re-recorded with a full orchestra. The song addresses an unseen lover; but it could also be a song that the audience might sing to the artist, since the animation feels exactly like an original Hollywood animation film, but is an independent artwork.

For some of the young generation of artists who comprise the rest of the show. 3-D provides another way in which reality can be rendered as artifice. New technologies have shifted our perception of the cinematic into a new optical experience in which, as Jim Hoberman argues, artifice and reality are becoming versions of each other. CGI has profoundly shifted the way in which space is depicted and experienced on screen. Trisha Baga’s installation ‘Flatlands’ is watched through 3D glasses. A mirrored disco ball placed on the floor front of the video catches light from the projection and reflects it onto the surrounding walls, creating different levels of immersion.

S&F: When you said the word immersive, the connotation that I have is gaming. I never thought about immersive cinema as applied to these early films which didn’t have a narrative, but were more visual experiences.

CI: In the earliest cinematic experiments by inventors such as Edison, the body was filmed emerging out of a pitch black space. This was also the case in the photographic experiments of Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, who photographed bodies against a dark gridded background. Marey plotted body movement through chrono-photography using a grid that resembles current motion-capturing techniques.

An important part of the show is our collaboration with Microscope Gallery to produce a number of expanded cinema works from the 1920s to the present. We are hoping to include works such as Kurt Schwerdtfeger’s shadow-light projection piece which he premiered in Kandinsky’s studio in Munich in 1922, as well as Stan VanDerBeek’s STEAM SCREENS, which was originally presented at the Whitney in 1971.

We are also exploring the possibility of re-presenting the Invisible Cinema at Microscope Gallery. The original cinema space was so black that the disembodied rectangle of the screen and the film inside it appear almost as a hallucinatory image. Immersiveness can be achieved either through light and color, or through deep darkness. It’s this latter model that connects to the experience of gaming and the Oculus Rift.

Another kind of immersion occurs in the collaborative video installation ‘Easternsports’ by Alex Da Corte and Jayson Musson, with a synesthetic soundtrack by the synaesthetic composer Dev Hynes. The work has four freestanding screen walls, on the other side of which colored neons reflect colored light into the space. A specially designed carpet and floor, colored chairs, and the smell of oranges, complete a synaesthetic environment created through music, light, color, images, touch, and smell.

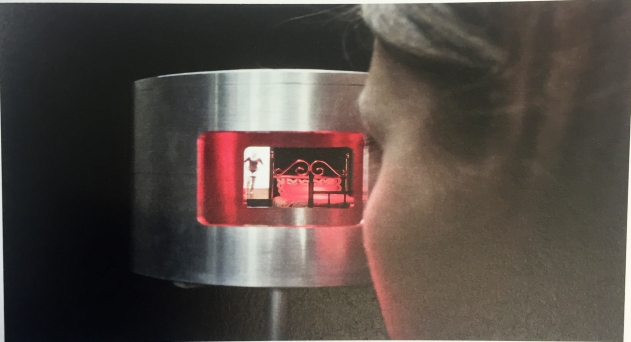

The show also includes a group of works by Lynn Hershman Leeson, including DiNA, an early Artificial Intelligence piece made in the 1990s. A female AI character played by the actress Tilda Swinton appears on a small mirror-shaped screen attached to the wall, who talks to viewers through a microphone. Another piece, ‘A Room of One’s Own,’ is a sculpture whose viewing conditions evoke the early Edison Kinetoscopes. We are also showing cyborg drawings and water woman drawings, in which the female body and technology become fused.

S&F: One thing I have been questioning is to what extent artists are trying to keep up with changing technology, and whether the technology is dictating the kinds of art being made?

CI: Artists always use whatever is around them. If a new technology appears, artists will engage with it and explore its possibilities in an experimental way that takes the technology into places it might never go otherwise. In BABY feat. IKARIA (2013), a work by Ian Cheng, a projection onto a tall upright screen leaning against the wall shows an animation of chatbots streamed from the internet, talking to each other, in a diversion of their original commercial purposes to artistic ends.

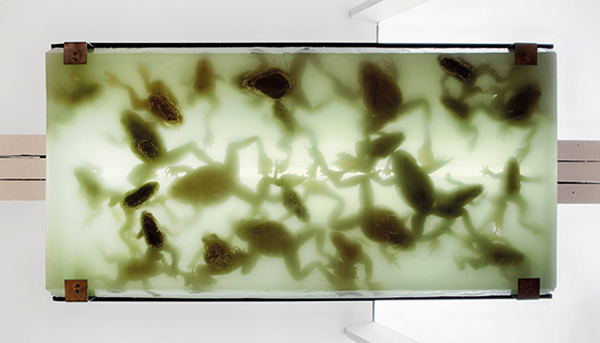

Dora Budor is making a cube-like structure which your presence activates. Once inside the cyborgian form, our movements cause parts of the ceiling to be lit up, revealing thousands of special effects frogs from the Hollywood film MAGNOLIA suspended in a clear resin, in another almost sinister fusion of nature and technology that evokes science fiction movies.

We are also showing TRADING FUTURES by Ben Coonley–a cardboard geodesic dome held together with file clips, inside which viewers wearing 3D glasses lie and watch an immersive 360-degree video projected onto the dome’s interior, combining high-tech and low-tech materials.

Frances Bodomo’s film AFRONAUTS will be presented in a gallery for the first time, as well as screened theatrically as part of an Afro-Futurist film program. The film is based on a true story, and addresses the failure of the Zambian space program as part of a wider black diasporic attempt to move beyond the sense of exclusion created by a white, Western technological vision of the future. Frances’s film has an important relationship to some of the earlier works in the show, and moves those questions forward. As in METROPOLIS, a male uses the female body to experiment with technology in order to realize his utopian fantasies of power, control and the future, that are doomed to failure, just as the broken bodies in Schlemmer’s TRIADIC BALLET articulate the failure of war. In Frances’ film the female protagonist escapes, and removes herself from the pressure to sacrifice herself to a male vision of national pride and power.

S&F: What will be in the screening program which accompanies the exhibition?

CI: Ten film and video programs will take place throughout the exhibition at the Whitney, and a group of expanded cinema works will be presented at Microscope Gallery in Bushwick, in collaboration with the museum. Alex Da Corte is also being commissioned by the Times Square Alliance Midnight Moment, and will show a video in their series, every night at midnight, through the month of January.

S&F: Are you exploring our immersion in technology and its use for surveillance in the show?

CI: Hito Steyerl’s FACTORY OF THE SUN addresses surveillance as part of an immersiveness in an image-drenched, virtual world, and questions the possibility of a collective resistance. Dreamlands as a sum of all these works becomes an all-surrounding sensorium.

Dreamlands will open on October 28, 2016 and run until February 5, 2017. The exhibition will take over the fifth floor gallery, and the screenings will be presented in the theater on the third floor. The catalogue for Dreamlands, with essays by Iles and other scholars in the field, will be published in conjunction with the exhibition.

Chrissie Iles is the Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz curator at the Whitney. She specializes in film and video installation, and the work of young artists. Her exhibitions include co-curating the 2004 and 2006 Whitney Biennials, and curating major survey exhibitions of Marina Abramovic, Dan Graham, Louise Bourgeois, Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, and Yoko Ono, as well as exhibitions of Paul McCarthy, James Lee Byars, Jack Goldstein, and several group exhibitions including Signs of the Times: Film, Video and Slide Installation and Britain in the 1980s, Scream and Scream Again: Film in Art, Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art 1964-1977, Off the Wall: Thirty Performative Actions, and Sharon Hayes: There’s So Much I Want to Say to You.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS