Making its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Sophie Jarvis’s debut feature UNTIL BRANCHES BEND follows a peach cannery employee named Robin (Grace Glowicki) who discovers a beetle she fears could be a threat to the supply chain. However, her attempts to sound the alarm are quashed by the men in charge, including her boss (Lochlyn Munro). Shot on 16mm on location in British Columbia’s Okanagan region, the film follows Robin’s frustrated path to follow her curiosity about the beetle and the loneliness it brings. At TIFF, we sat down with writer-director Sophie Jarvis to discuss the research that went into the film, the importance of its setting, and her next projects.

Sloan Science & Film: UNTIL BRANCHES BENDis a film that has a lot of layers and at the same time is very place-based and specific. What research went into the film?

Sophie Jarvis: Research was a big part of the film because I’m a filmmaker and not a scientist, so as much as my film has this idea of a little bug that is potentially invasive, I knew that to make that world feel real I’d have to do a lot of research. That included talking to entomologists at the research station in Summerland [in the Okanagan region] and talking to farmers and orchardists. I also talked to different types of farmers, like those who were there since colonization, and also ones who immigrated in the 70s. I wanted to understand the world that exists in the Okanagan around farming.

I talked to a lot of entomologists to help develop what type of bug this could be. It was based on the codling moth which is a real bug that messes with apple trees. For a long time, I think in the 80s and 90s, a lot of farmers lost their farms to it because it destroyed their trees. We went to the research station in Summerland which is a really incredible building; we weren’t allowed to shoot inside of it because it’s a federal building, but they did let us shoot in the parking lot. When you see the building, it feels like a very 60s brutalist structure. Then one of the scientists took us into his little lab and I laughed when we walked in because it was like he was given $50 to spend at Home Hardware and bought sticks, glue, some netting, and had to make a high-tech station to do his research. The building has this incredible look–like oh wow, science, money–but then you go in and see these people are really scrappy and have to make do with limited resources.

With the codling moth, they began a sterilization program at the research station. They would breed and sterilize moths but then also feed them an all-pink diet so they could track how they were mating with wild moths and how well this plan was working. It worked really well and is still used today. I thought the idea of these tiny creatures being such a problem would be an interesting story. So, we developed the bug very heavily inspired by the codling moth and called it the spear beetle.

Because we had a limited budget as well, the bug we used is called a darkling beetle which is a very common black beetle. The markings on its back were developed with a concept artist and I had an entomologist weighing in to make sure that we weren’t copying a bug that already exists. We would shoot with the real darkling beetle, we wouldn’t paint on it, then we had VFX put the markings on. We also had some props fabricators mold hundreds of these bugs that could be painted, because a lot that you see in the film are dead.

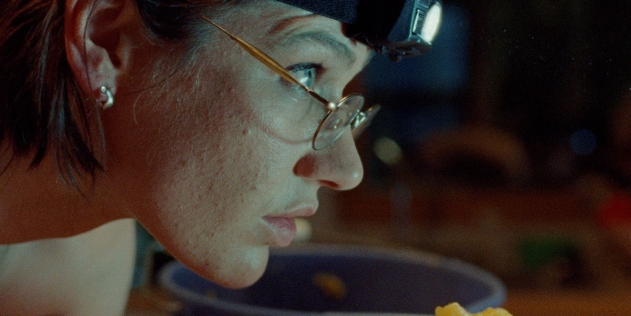

Grace Glowicki in UNTIL BRANCHES BEND. Image courtesy of TIFF.

S&F: That’s very involved!

SJ: It was really involved! And it was important to me to understand the supply chain issues. Robin works in a factory, the factory is processing the fruit from the farmers, and the consumer receives it. There are a lot of people affected, not just those who are growing the fruit or who are processing it.

The understanding I got is that when these bugs come, they affect one crop only. We live in British Columbia, which is unceded territory, so we don’t have any treaties signed with the First Nations who live there. The area we were shooting on is Sylix Territory and the diversity in the flora and fauna is indigenous and not affected by these bugs. Colonization is another sub-plot of the film. Monoculture is a colonizers thing. I met really wonderful farmers while we were making this film and I don’t think they’re to blame. This is what they do and it’s also what we all benefit from—I can’t wait for the summertime when I can eat peaches. I think it’s a really complicated issue rooted in capitalism and colonization, and I don’t have a solution, but the story that I’m telling is showing what could happen and who would be affected. That’s something that needs to be talked about more—I didn’t know much about it before starting this film!

I will also say this: I think golf courses are stupid. To have them in a landscape like that? I was really intent on showing one in the film to show another way that the land gets modified for some capitalistic reason.

S&F: Robin, your main character isn’t a scientist, she just discovers this bug, but the scientists and people she’s trying to report this to are all men who lack a certain amount of curiosity and are dismissive. Can you talk about those gender distinctions?

SJ: That was a choice. I’m all for not going for the immediate “scientist, man.” I would love to gender-swap that, but in the case of the story I really wanted to show Robin up against patriarchy and against the society we live in. She’s trying to get an abortion and there are all these bureaucratic reasons she can’t which exist because of the patriarchy. To get anyone to listen to her about the bug she has to go through all these men who dismiss her. So, it was a choice to have a white, male scientist which was more in line with the themes of the story. It’s not to say that women can’t also be participating in the patriarchy, but I just felt like visually and for a short scene it would be easier to show that Robin is yet again trying to talk to a man who isn’t listening.

S&F: How did you conceive of the look of the film?

SJ: A lot of what made me want to tell the story is that I’ve spent a lot of time in this place. My grandparents live in Summerland and my mom grew up there. I spent a lot of my childhood visiting. It’s called Summerland also which is too perfect. My grandfather was an incredible gardener. Going there it always felt like this place of abundance and tranquility modeled off a Bavarian aesthetic. There is something about that palette and location that were innate. As a production designer, I wanted to draw from that. All the pastels, textures, even the peach skin, the dust that’s on the windshields, those are details that you can pull from. Unfortunately, wildfires are raging all the time. While we were shooting it was really smokey and between that and shooting on 16mm we got this very atmospheric effect which looks good, but I also wish it wasn’t the case. There were days when it was so smokey that you couldn’t see the view.

S&F: Do you know yet what’s next for the film, or for you?

SJ: We’re going to be doing a Canadian festival tour that ends in Vancouver where most of our cast and crew are so I’m really looking forward to that. We have an international premiere, but we’re not allowed to say what it is yet. For me, I’m looking forward to making more work. I’m developing another feature right now, and Grace is attached to that too. She’s a big part of the process.

S&F: Do you think this film will find an audience amongst entomologists?

SJ: I hope so! Man, we talked to so many entomologists and I tried my best to honor what they told me, and for the most part they all told me this was 100% possible. Even down to the design of the beetle, to talk about whether it has chewing properties—that’s a word to describe bugs that chew through things—or is it a sucking beetle or can it fly. There are a lot of different characteristics to beetles that I didn’t know about. We crafted the perfect beetle together and they told me that the story checked out. So, I’m very curious and nervous for entomologists to watch it. I think all the ones I talked to probably don’t know what the film’s about, they probably think it’s just about the bug, and they’re going to watch it and be like, what’s all this other stuff? But I’m down for them to see it and I’ll take a report card afterwards.

♦

TOPICS