In 1895, physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered a new kind of imaging technology, using electromagnetic radiation that can pass through physical substances, like skin, that usually form a barrier to visible light and thus to human vision. X-rays imprint shadows of what they cannot penetrate on film, producing pictures of the body’s internal structures. In other words, they make visible the hard structures, especially bones, that are usually hidden by skin and flesh, invisible except when exposed by traumatic injury, invasive surgery, or postmortem dissection. In naming his new discovery, Röntgen used the unknown variable “x” as a placeholder. But “X-ray” caught on, perhaps sustaining a sense of mystery that still surrounds the capacity to visualize what is normally—naturally—hidden from human sight.

One of the first X-ray images Röntgen made was of his wife’s hand.[1] Her response was more horror than wonder: “I have seen my death,” she is reported to have said. Rendering flesh invisible or transparent, X-rays mimic the decomposition that follows death. Such access is enormously useful to medicine—but, as Mrs. Röntgen immediately recognized, it is also a memento mori, a reminder of the skull beneath the skin, of the fact that we are all already skeletons. Roger Corman’s science-fiction film, X: THE MAN WITH THE X-RAY EYES, takes the medical ideal of seeing inside living bodies to its logical—though not plausible—extreme, playing with the fantasy of omniscience and with the disturbing, even deadly, implications that accompany it.

Released in 1963 (a week before the assassination of JFK), X tells the story of Dr. James Xavier (played by Ray Milland), a physician-scientist who develops a substance that changes the structure and function of the eye, giving it the capacity to see beyond the normal limits of human vision, through layers and beneath the surface of things.[2] The idea of “X-ray eyes” combines two medical ideals into one paradoxical problem. We want to know more about patients’ bodies by looking inside them, and we want to increase human wellbeing by enhancing bodies’ capacities. Dr. Xavier’s X-ray vision—for he tests it successfully on himself—takes the physics of imaging machines and makes it into a biological prosthetic enhancement, making the research subject (or, now, patient-practitioner-technician) into a kind of biomedical machine. Subject and object of medical scrutiny are combined into one fascinating and disturbing hybrid, Dr. Xavier himself, in the mysterious eyes of “X.”

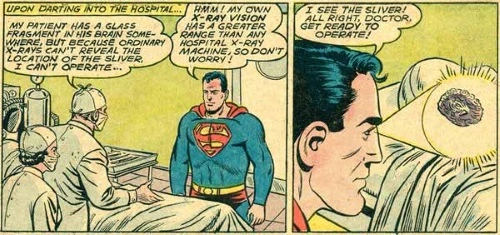

The fantasy of human X-ray vision was very familiar by the 1960s, thanks to the Superman comics. Superman’s "x-ray eyesight" first appeared in 1939, when he looked through a building’s walls to see what criminals were up to inside. His superpower was also used medically, though only much later, in a 1974 comic, where Superman stands in for the X-ray machine in an operating room.[3] But the fact that the technology works by emitting rays (rather than receiving light as the eye does) added another element to the superpower: in 1949 (issue no. 59), Superman tried to look inside a glacier with his X-ray vision; when that didn’t work, he used the rays to melt the glacier instead.[4] From then on, Superman’s eyes projected various lethal beams. The perceptual power had been weaponized.

Of course, we know that X-rays really are a bit like the death rays Superman shoots out: ionizing radiation can do real harm to organic material it encounters. In the 1940s, X-ray machines became a popular fixture in shoe stores, claiming to improve fit, especially for children, and causing significant harm to salespeople continually exposed to radiation.[5] Far earlier than that, in 1904, Thomas Edison turned away from his own work on X-ray technology after his assistant Clarence Dally died of X-ray exposure—probably the first person to suffer this fate.[6]This ominous turn from scientific optimism to the ethics of risk and harm plays out in X. Beginning with the relatively simple concept of enhanced perception, Xavier’s self-experimentation is already dubious in terms of research ethics (done this way because of all-too-familiar pressure to sustain his grant funding), but it’s a real risk only to his own safety. We are diverted by the comic implications of his superpower, echoing the familiar joke advertising for “X-Ray Spex”: Dr. Xavier finds he can see through clothing tothe naked bodies underneath, an ability he enjoys making use of at a dance party.[7] Later he also uses the ability to cheat at cards in a Las Vegas casino.

More seriously and significantly, Dr. Xavier is able to use his vision the way X-ray technology is intended, looking for signs of pathology inside human bodies. He develops a clinical role, working with—and exploited by—a colleague who uses him as a kind of human imaging machine. But the work takes a toll, as Xavier find himself less and less capable of seeing patients as people rather than layers of tissue he must penetrate with his eyes. He realizes that identifying disease is not the same as treating it: “I can’t heal,” he complains. “I can only look. I tell what I see.” Suffering a kind of burnout, and needing increasingly high doses of his X-ray inducing eyedrops, Xavier eventually flees into the desert. Near the end of the film, we have moved into a kind of cosmic horror, and Xavier is questioning whether humans should be allseeing in a vast and terrifying universe.

In this way, Xis a familiar cautionary tale about bioethics and the risks of “playing god.” Dr. Xavier’s work is impossibly successful and causes terrible harm—he is a clear descendent of Victor Frankenstein, but the monster he creates is himself. We are warned of this early on when Xavier’s friend, an optician monitoring the eye experiments, hears Xavier complain that normal people are “blind to all but a tenth of the universe” because the “range of human vision is less than one tenth of the wave spectrum.” Xavier asks, “What could we really see if we had access to the other 90%?” His friend drily observes that “only the gods see everything,” and Xavier’s response exhibits the hubris of the overweening “mad scientist”: “My dear doctor, I’m closing in on the gods.”

With each dose of the drops, Xavier’s vision becomes stronger, able to see through more and more layers. The observable universe keeps expanding for him and at first, he is delighted: “Soon I’ll be able to see what no man has ever seen. … With new eyes, we can explore all the mysteries of creation!” But the film nudges us toward the physical paradox that being able to see through whatever we are looking at means that everything eventually becomes invisible. The power reaches an ideal balance when it functions medically, seeing inside patients’ bodies, but this is a temporary stage. Soon Xavier no longer has human vision and can hardly see people at all.

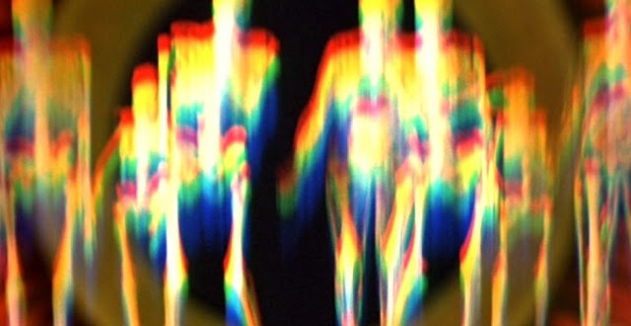

At the end of the film, we see through X’s eyes: a fantastically surreal, nightmarish world (created by John C. Howard’s “Spectarama” special effects[8]). Xavier ends up at a religious revival meeting and makes his apocalyptic announcement: “I’ve come to tell you what I see. There are great darknesses, farther than time itself.” Then, he puts out his own eyes, in the end a kind of Oedipus who has seen more of tragic reality than his mind can tolerate.

The hubris that Xaddresses in the early 1960s is consistent with a deep ambivalence about scientific and technological developments. The risks associated with medical uses of radiation at the time were balanced by the increasingly clear benefits, with X-ray technology being used to treat cancer even while over-exposure was known to cause the disease.[9] At the same time, Cold War anxieties about nuclear radiation had generated enough public attention that in 1960 the Times published a reassuring article about a condition it called “radiophobia,” or “nuclear neurosis”: the “unwarranted fear” of medical radiation.[10] The tradeoffs associated with the medical use of X-ray technology are a question of bioethics: is the benefit worth the harm?. In 1963, Roger Corman’s film, with its imaginary merger of X-ray machine and human body, gave us a profound picture of the stakes of human ambition, one that is perhaps more compelling now than ever.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Röntgen#/media/File:First_medical_X-ray_by_Wilhelm_Röntgen_of_his_wife_Anna_Bertha_Ludwig's_hand_-_18951222.jpg

[2]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X:_The_Man_with_the_X-ray_Eyes#/media/File:X-RayEyes_Rep.jpg

[3]https://medium.com/stanford-ai-for-healthcare/superman-isnt-the-only-one-with-x-ray-vision-deep-learning-for-ct-scans-290aaa7ba5c1

[4] http://www.kleefeldoncomics.com/2020/07/supermans-developing-power-set.html

[5] https://clickamericana.com/topics/health-medicine/how-x-ray-shoe-fittings-used-to-really-be-a-thing-years-ago

[6] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/clarence-dally-the-man-who-gave-thomas-edison-x-ray-vision-123713565/

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-ray_specs#/media/File:X-Ray_Spex.jpg

[8] https://www.spectarama.com/blog/x-the-man-with-the-x-ray-eyes.html

[9] https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1937/5/10/million-volt-x-ray-machine-replaces-former-cancer-killer/

[10] https://www.newspapers.com/article/-unwarranted-fear-radiophobia-1960/10421056/

More from Sloan Science and Film:

TOPICS