ALL THAT BREATHES, set in New Delhi, is a documentary following two Muslim brothers who have formed a unique kinship with black kite birds by creating a makeshift care facility for injured kites. Other Indian animal hospitals refuse to take in the birds because they are carnivorous—they eat meat, which the majority Hindu population in India does not. The first film to win both the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and Best Documentary at Cannes, ALL THAT BREATHES has garnered awards at festivals and award ceremonies around the world. It was most recently nominated for Best Documentary at the 2022 Gotham Awards. We spoke with director Shaunak Sen about his entry into the subject, his view on environmental filmmaking, and the layers of the film’s story. ALL THAT BREATHES is currently in theaters.

Science & Film: What was the starting point for this film?

Shaunak Sen: If you’ve been in Delhi over the past few years, the air has a pervasive presence–the sky is this monochromatic expanse, and you’re constantly aware of the air you are breathing in. It is a heavy, opaque substance. I was getting interested in making something about the triangulation of air, bird, and human. If I had to pinpoint one instance where this film started: I was sitting in a car in a traffic jam, and I remember looking up. The black kites are usually these lazy dots in the sky. I had the distinct impression that one of them was falling out of the sky. I was gripped by this [image of] one bird falling out of a heavy, polluted sky.

I was very interested in the environment, but I would grow impatient with what felt like bleeding heart sentimentality or a doom and gloom despair [in films]. It doesn’t do much good because you’re putting people off. I got interested in this [story] because one can emotionally move people. I am interested in the ecological sublime and questions of the planetary perspective.

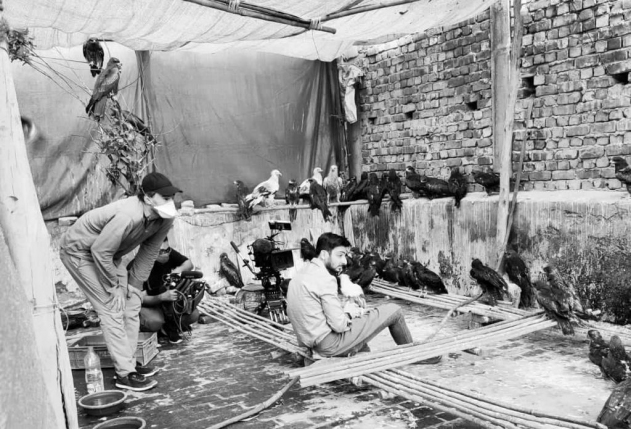

Still from ALL THAT BREATHES, courtesy of the filmmakers

S&F: Why were the brothers particularly interesting to you?

SS: Their basement is a very damp, derelict, claustrophobic basement with these heavy industrial machines on one side and these regal birds on the other; it’s such a deliciously dense, cinematically romantic space. The brothers have a kind of rye resilience—a put your head down and get the work done sensibility—which I really liked and that’s how I was drawn into it.

S&F: I noticed in the credits that you had a science advisor, who were they and what was their role?

SS: Our producers and financiers, they work often at the intersection of creative doc and science doc. A lot of their documentaries are interested in the natural world. Accuracy and precision are important. So, it was great to have Andrew Gosler who came in [as a science advisor]. It was really lovely to have scientists as constant interlocutors. Nobody on the team has any experience nor ambition to tell a conventional, wildlife, nature doc story. The whole ambition was to tell a creative, poetic story. I never wanted to make a sweet film about nice people doing good things.

The idea was to try to excavate the layers of the story, and the layers were threefold. One: the emotional life of the brothers, their inner life. It’s not easy—their families are often annoyed with them. They soldier on despite the toughness of the circumstances. Apart from that there is the social unrest on the streets. The city was going through a turbulent time. That leaks into [the brothers’] lives. Thirdly, I was interested in the city itself as a space where human and non-human lives are constantly jostling cheek by jowl. There is a kind of improvisation and forward momentum evolutionarily to lives in the city. All in all, we had to meld all these different layers.

Behind the scenes of ALL THAT BREATHES, courtesy of Sideshow and Submarine Deluxe

S&F: I think the pandemic has made people generally more fearful of human and non-human animal proximity. Between when you shot the film and its release, has your relationship to the subject and to that entanglement changed?

SS: The film took us three years, from 2019 to 2021. In creative nonfiction, three years of shooting is not that long. Also, it’s not the kind of story that gets outdated; it’s about human-animal relationships. So, you’re consciously talking about zoomed out abstractions. Even if someone sees this film in 15 years, it could still be relevant. When the pandemic came, it changed our relationship to nature and Earth as a kind of blunt force which can be hostile. There are zoonotic diseases, but animals are also helping maintain the microbiota of the world. There is a tendency since the pandemic to look at animals as vectors of zoonotic disease, but there is a flip side. Hopefully the film is able to activate those empathy neuron clusters in people’s brains, and hopefully people will walk out of the theater and look up.

♦

TOPICS