The stunning new documentary from the filmmakers of LEVIATHAN, Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA goes inside 43 Parisian public hospitals, inside the bodies of its patients, embedding within surgeries to give viewers an almost transgressive encounter with the corporeal. The film made its world premiere at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival and we sat down with the filmmakers at its U.S. premiere at the New York Film Festival, where discussed the multiple origins of the project, the filmmakers’ process, technique, and ambitions. DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA will be distributed by Grasshopper Film in 2023.

Science & Film: What were this film’s origins?

Lucien Castaing-Taylor: The origin of this film, [speaking to Véréna] we each compete to have the worst memory, when I’ve heard you talk about it I find it more credible than my faulty memory. We had this adage, if you can’t get into Harvard when you’re alive, you can get in when you’re dead.

Véréna Paravel: Because of the prestige of Harvard and people wanting to give their body science, you can donate it to Harvard.

L C-T: But Harvard has so many cadavers it doesn’t know what to do with them, so it sells them to other places that don’t have enough; it chops them up and sends body parts around the world.

VP: This made me laugh and then I told you I knew someone doing a PhD at Harvard in sociology, we met him.

S&F: Was it specifically surgery, or bodies, or death, or hospitals that you were interested in?

L C-T: It was specifically all of those different things, which is to say that our ideas were all over the place. If it’s Errol Morris or a real documentarian, they have a precise idea or a person they want to follow. We have a multiplicity of semi-formed ideas and we don’t know which will get traction in the real world when we start filming. Our documentaries are so unscripted. But we are also obliged to try to fund them in some way—at least we used to be, now we can’t get any money. We used to be able to get money from American foundations, so we had to write applications pretending to know what the film is about. LEVIATHAN was all about Guatemalan black-market labor in the Port of New Bedford. [For this film] we wrote an application that we got funding for and half believed it, a really stupid idea, that [DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA] would consist of seven chapters featuring seven different medical imaging devices used in cutting-edge surgeries. Then we started trying to film in Boston and that was really about surgeries—hand surgeries and face transplants. Even when we started in Paris we didn’t know what we were doing.

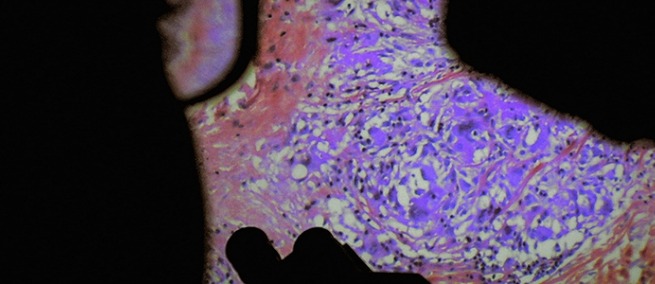

A scene from DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA. Courtsey Grasshopper Film and Gratitude Films.

VP: Rather than a clear idea, it’s always an ambition. What if we were to make a film about the ocean where you could evoke the ocean and what it is? It’s so abstract at the beginning then becomes something after years of being there. This time the ambition, and I’m talking about an ambition rather than a concept because it’s ambitious and it’s unclear—it’s more like a volonté [Lucien: a will or desire], an aim, but that is still abstract. For this film it was to try to make a film where, after you’ve seen it, you will have a different feeling of your existence in relationship to the world and your own interiority.

L C-T: In this film, we got unlimited access to these French hospitals quite early on, so we deliberately did not want to hone in on something. It was only after years of filming and editing that it began to coalesce. We were spared the need to clarify our ambition because we got such broad access—any single hospital is infinite, and we got access to all 43.

Another source of inspiration was Henry Marsh’s writing. He is a British neurosurgeon, very good writer, Do No Harm was one of his big books.

S&F: I heard you at TIFF speak about Walter Benjamin and the optical unconscious, was that part of the original conceit of the film?

L C-T: I’m an academic and you have to keep on getting hired so you don’t get fired and write these things about your future research. I did once write a document saying I wanted to make a film about surgeons and rituals, “scrubbing in” especially and how they get into a space where they can transgress the body. I remember having to sound very intellectual. Benjamin compares the optical unconscious to the psychoanalytic unconscious and is that really a useful analogy? He talks about the optical unconscious being opened up by the motion picture camera which then blows the prison world asunder in a fragment of a tenth of a second—I’m quoting from memory. It was very Vertovian this notion of what the camera could show that the human eye couldn’t show. The whole idea was that the human eye sees in an encultured way, and the cine-eye sees something that we can’t see precisely because it’s not human. But then how he could maintain an equivalence with unconscious desires, I don’t know.

S&F: How did you embed yourselves in the hospital rooms? You obviously got very close, but the surgeries were still successful.

L C-T: I don’t think it was different from any of our other films. I don’t think we find it very hard; people say, how did you do that? I think most documentarians don’t try hard enough, or don’t want to anymore because everything’s performative or cinema vérité is démodé. It’s not as though we have a formula except hanging out, spending time, and we’re curious about everything so we’re both inferior to [the doctors] because the doctor’s know a lot more than we do, but we’re also coming in from Harvard so they’re willing to give us the time of day, or not if they didn’t want to be observed, but most of them were willing. Even though they have a lot of banter amongst themselves, it’s quite cognitively demanding what they’re doing, so it’s easy for them to forget about us. The neurologist featured in the film was in the middle of a procedure, doing the robotically operated radical mastectomy, and I remember he looked at me at one point, looked at Véréna and said, it’s not normal that I haven’t had an erection today. So, did we embed ourselves successfully if in the middle of an operation he can turn and make jokes to us? Embedding is not becoming invisible but becoming part of the fabric.

VP: I think they understand that the work we’re doing is not typical. There is something about the way we explain without explaining what we are after, because we don’t exactly know, but at least we tell them that we are not in the position of a journalist who tries to have a message that is already clear conceptually. On the contrary, we are a little bit lost there. We want to spend time with them, we want to be next to them, very close, we want to understand. What we’re doing is mostly research and we will take time. It gives them the possibility of relaxing. Sometimes if you come in and put a spotlight on for one hour or one surgery, they would just manifest their best. [We are there] without a precise goal except to feel what their work is about, what the body is about, and to be passionate about what they’re passionate about and try to understand that.

A scene from DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA. Courtsey Grasshopper Film and Gratitude Films.

L C-T: The craniofacial pediatric surgeon we ended up not filming, remember him? He was just like, what is your point? What are you after? It wasn’t so much that he was mistaking us for journalists, he was mistaking us for scientists. He assumed that we had hypotheses we wished to test. But we have none, you are a mystery to us, this is unknown, we just want to see what is secreted by the place through the camera onto us in some sense.

VP: But I think that is actually much more interesting because if you tell people, I’m after that, they will try to constrain their movement towards what you want. People always have an idea of what a documentary is because they have a TV, sadly. When you just tell them that you want to study them as a tribe, like any anthropologist would study a group of people, suddenly they feel part of this tribe and then there is nothing they can do except their job.

L C-T: It also became very clear to us that every operation, no matter how banal, is an experiment. None of them can anticipate how it will go, and they don’t expect it go just like the previous one, even for something super quotidian they do five times a day.

S&F: In terms of technique, were you filming screens, or putting your own cameras inside the body? How did you get that intense sound?

L C-T: We did film screens but maybe one ended up in the film—in the urology surgery, and the image in the spinal surgery. The first surgery we really shot was this hepatic surgery and we were filming with DSLR. We looked at the footage and it was a bit closer, a bit more beautiful than what you see on TV but felt déjà vu. We really wanted to be inside the body in way that doctors commonly see, and YouTube watchers see—we hadn’t looked at any YouTube and I’m sure this is really banal compared to what’s up there. There is an audience for this stuff, but it was new for us and for many spectators who come see our film.

When [surgeons] were using laparoscopic or endoscopic or oscilloscopic cameras for the surgeries and that camera was projecting onto a screen that they would use to guide themselves, we were simultaneously downloading the footage. It was being temporarily downloaded onto their screen and permanently downloaded onto our recording device. We were recording ourselves with a handmade pseudo-laparoscopic camera; it wasn’t quite as small, it wasn’t sterile. Then we recorded sound in sync with that and separate double systems as well so we could sync them all up afterwards. The sound was recorded from the microphone attached to the laparoscopic camera.

VP: In the beginning we didn’t have any sound, we were filming like back in the old days.

L C-T: We just had double-system sound which was not very good at recording and really bad at slating. Slating is the percussive sound you make and include in the image so you can sync sound and image. With our sound designer we worked on different bodies with hydrophones inside orifices and contact microphones which work much better on hard, flat surfaces but record flesh differently. Lots of different sources of sound.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel.

S&F: I noticed in the credits you had a senior medical advisor. Who was he and how did you engage him?

VP: He came in at the end. In a way, we had medical advisors all the way through the filming, because our subjects were all advisors to us. It’s always fascinating to film people who are extremely passionate about what they’re doing, and very often we would ask them, what is the most amazing surgery you’ve seen? What is your favorite organ? We were always curious. That’s how we navigated through the body and hospital. One person would say, have you talked to the dermatologist? Have you talked to the anatomopath [pathologist]? No, that must be boring, they are the ones analyzing slides, but it was amazing.

The medical advisor watched a rough cut towards the end, and the reaction was amazing to me for two reasons: one, he was jumping up and down in joy, literally, and we were really surprised to see how happy he was. He was mostly happy because he was extremely excited to discover other surgeries that he didn’t know about—he said, oh, I always wanted to know how you do a [that] brain surgery. The most interesting comment was, all of your surgeries are soft-tissue surgeries, and you have to have some bones, otherwise it's going to be just flesh.

L C-T: He’s an osteo.

VP: We thought, you’re preaching for your own church. He convinced us to come watch some pediatric orthopedic surgery. We were not completely convinced but we went, and saw several beautiful spine surgeries, then this magnificent shoulder surgery where they take the tendons from inside the thigh and try to put them on the shoulder to make the shoulder move again. It is a really beautiful and very long and complicated surgery with two groups of surgeons operating at the same time. Completely amazing surgery. Then, we realized that once we put the bone surgery inside the flesh of the film, the film had a structure. The film was holding itself much better. I realized, and I think we all had this discussion while watching the back surgery, that when you hear the bones, you really feel what it is to have a body. I completely understand what he meant when he said, you need to have some bones there.

L C-T: He was also incredibly helpful with subtitling. When we couldn’t understand what the doctors were saying, when the doctors themselves couldn’t understand what they were saying, he listened to things repeatedly trying to work out exactly what was said.

VP: And he taught us a lot about medical culture. What doctors do when they go to a party, what they drink, what they listen to. At the end what was most important to us was that the doctors recognize themselves in the film. We wanted to make sure we were not portraying them in the wrong way, and that the sync sound was perfect, and when we cut things we didn’t make a mistake. That was rigorous work. We don’t take six years to make a work for it to not be rigorous.

♦

TOPICS