In BIRDS OF AMERICA (2021), a feature-length documentary directed by Jacques Loeuille, we cruise the Mississippi River in pursuit of John James Audubon, the 19th-century painter and ornithologist whose art book of the same name acts as an epic illustrative record of every avian species in the United States at the time of its creation.

Audubon’s project took more than a decade to come to fruition—and cost him about $1.5 million in today’s money to produce—but it made his name, recorded at least 25 species as yet unknown to science and is now recognised as a landmark work of environmental art. Birds of America is now considered the world’s most valuable printed book. America’s oldest bird conservation organisation, the Audubon Society, was named in his honour.

Audubon’s book is a time capsule as much as a work of art; since its first publication in 1827, a number of the species he so carefully portrayed have been declared extinct. Those painstaking designs now appear as a souvenir from some more innocent era. Loeuille’s film interweaves the stories of these phantom birds (including some, like the ivory-billed woodpecker whose continued existence is a matter of debate) with interviews with representatives from indigenous groups, whose native territories have been terraformed by industry in the years since the book’s publication. This is the story of the wholesale corrupting of the land—and, by extension, the American soul.

Minneapolis Public Library Science Museum staff flipping through an original volume of John J. Audubon's 'Birds of America.' Image courtesy Hennepin County Library.

“In this New World, the biggest polluters of the planet adorn themselves in good intentions,” warns Loeuille. We follow the river into an oil field region of the Gulf Coast, donated by the oil company Exxon Mobil to The Nature Conservancy for preservation of the prairie chicken, a once ubiquitous American bird that, even by the time of Audubon, was well on the way to extinction. (The prairie chicken, also known as the pinnated grouse, was hated by farmers for pecking at unripe fruit, and for eating the seed scattered on the fields. In his diary, Audubon wrote that a friend of his, “who was fond of practising rifle-shooting, killed upwards of forty in one morning, but picked none of them up, so satiated with Grouse was he, as well as every member of his family.” The population soon nosedived; they are now considered critically endangered.)

To the shock of fellow conservationists, The Nature Conservancy decided to exploit the oil remaining in their new Louisiana reserve, sinking a new well alongside the birds’ preferred nesting area. The last prairie chickens, Loeuille tells us, left in 2012. We glide through the region by boat, in the company of a Pointe-au-Chien guide—and find it an uncanny ghostscape of blackened reeds and dead trees. This is a haunted landscape, where the sins of the past are etched into the face of the earth.

Loeuille spirits us to the Audubon Zoo in New Orleans: “a vast artificial paradise where the surviving birds take refuge in scenarios created by huge oil companies.” Two dozen flamingos—familiar from one of Audubon’s most beloved paintings—preen in a packed-dirt enclosure. Then onwards, to the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas, where staff once worked frantically to save sea turtles and other rare marine species caked with thick crude oil in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2010. Now, in the aquarium’s vast tanks, glittering fish, sharks, and rays swim between metal struts designed to appear like the base of an oil rig. The camera pauses to take in an illuminated sign: sponsored by BP, Shell, Exxon Mobil, Chevron… This is, we must realise, a false idyll. As, to some extent, was Audubon’s Birds of America, produced as it was in an America whose colonial and industrial ravaging was already well underway.

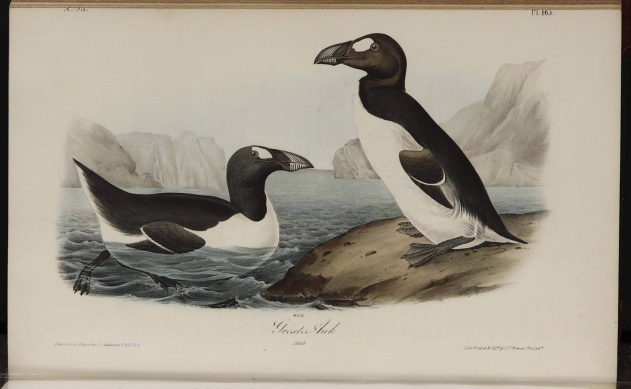

Plate from the first edition of 'Birds of America.' Courtesy The State Historical Society of Missouri Library Collection.

It is this discomfiting sense of poisoned oases and corrupted nature that pursues us into Alex Garland’s hallucinatory sci-fi vision ANNIHILATION (2018), based (very loosely) on the novel by Jeff VanderMeer. Here, the source of the contamination is extra-terrestrial not industrial: a cancer-like affliction brought to Earth by meteorite, and which has created a slowly expanding strangeland known as Area X, or, colloquially: ‘The Shimmer.’

The nature of The Shimmer is not yet clear. Radio signals are unable to penetrate its glistening force field. An offshoot of the US government has dispatched a number of reconnaissance missions into the region, none of which have returned. Until now.

We meet Lena (Natalie Portman), a professor of biology whose husband (Oscar Isaac) reappears inexplicably, a year after his departure on a special forces operation into the zone. The husband, hollow-eyed, is amnesiac and confused, not himself; when she calls an ambulance, they are intercepted and taken to the headquarters of the Southern Reach, a mysterious research department perched unsteadily on The Shimmer’s outer edge.

Still from ANNIHILATION

Soon, frantic with grief and racked by guilt, Lena volunteers for what she must know to be a suicide mission into the zone. She, along with four other female scientists and medics, soon find themselves disoriented and confused inside Area X, a region where plants and animals mutate and take strange forms. The compass spins wildly. Their communication equipment is rendered useless. They take direction from the sun only; head south, towards the coast and the source of the contamination.

Inside The Shimmer it is verdant, green. The low sun casts long shadows, everything lit in shifting technicolour. They find wildflowers clambering walls and balustrades—orchids, hollyhocks, all kinds of flower heads grown from the same branch. Later, a horrifying bear-like creature kills one of their number, then speaks in her voice. Colourful lichens spread over walls, “malignant,” as Lena quickly identifies them, “as tumours.” Later, she will inform a masked interrogator: “It was dreamlike… Sometimes it was beautiful.”

Garland’s ANNIHILATION—which departs significantly from the plot of the original novel—serves as a sort of environmental allegory, and especially when viewed in tandem with BIRDS OF AMERICA. The two films, however different in tone and style, present strange parallels. Images from one arise unbidden in the other.

In the Aquarium of the Americas, we met a rare white (leucisitic) alligator, taken as a hatchling from the Louisiana swamps; in ANNIHILATION we watch aghast as a giant, pale-bellied alligator lurches from its lair in a half-sunk cabin, grasping one of the soldiers by her backpack and pulling her under. The surface of the water—and the sky, as seen through the veil of The Shimmer—is aswirl with the rainbow iridescence of petroleum.

These echoes are not entirely coincidental. Garland has previously suggested that he took inspiration from the Gulf oil spill of 2010, and oil slick imagery is omnipresent throughout. “It was about trying to construct images that could be both beautiful and seductive, but also sinister at the same time,” Garland noted. In this, he has succeeded, to fantastical effect. Kudzu reclaims abandoned houses and cars. Powerlines slump, their wires wreathed in flowers. Eerie, spindly white deer with cherry blossom boughs for antlers flee from Lena’s approach.

Still from ANNIHILATION

Still, The Shimmer’s effects on the environment are different, otherworldly: the muted watercolour light of the zone alludes to its function—The Shimmer acts like a prism, bending not only light, but radio waves and biological matter. Human DNA is spliced with the genetic matter of the plants and animals that once lived inside Area X, producing strange and horrifying chimeras. Shrub-like clumps of wildflowers take bipedal form, like a frieze of treefolk emerging from the undergrowth. Tree roots spill from the earth like entrails.

ANNIHILATION’s unsettling beauty is undercut with flashes of body horror. We watch a man sliced open to reveal his intestines writhing like a nest of snakes. Exploring the abandoned former headquarters of the Southern Reach, the soldiers discover a human corpse exploded apart and bonded to the wall by only semi-recognisable organic matter. Lena samples her own blood, then examines it under a microscope, pushes her chair back in shock at what she sees. “We’re disintegrating,” her superior advises her. “Can’t you feel it?”

Journalistic and documentary coverage of such issues offer us more insight into the harm we wreak upon our home planet than ever before. But it is easy to become habituated to these images of environmental degradation and destruction; after a while, it loses the capacity to shock. We become jaded, hardened to ever-more apocalyptic reports.

Jeff VanderMeer’s book offered a fresh approach to this greater narrative—a view of the unholy truth, albeit seen through a distorting prism—and Alex Garland’s adaptation amplifies that vision, turning the visual language of the disaster movie and the tropes of horror to the same end.

Sometimes it is easy to avoid the newspapers, or to switch channels when the evening news comes on. In ANNIHILATION, we find a vision of environmental collapse so primally disturbing that we cannot look away. Its takeaways are ambiguous. The Shimmer, claims Lena, in a tense debrief interview, is morally neutral. It does not destroy, only changes whatever it comes into contact with. In this, we too find parallels in the real world—where forests and wildlife and fish stocks shift northwards in response to climatological change.

ANNIHILATION does not, in other words, offer us a route map for the future. But then: the path is dark and overgrown. We cannot fully know what we will encounter up ahead.

TOPICS