Before humans launched into outer space, there were animals. Beginning with fruit flies, the U.S. and the Soviet Union experimented with the ability of different creatures to withstand the flight’s harsh conditions. SPACE DOGS is a new documentary which explores the life of the first animal to make it into orbit—a dog named Laika, who was launched by the Soviet Union in 1957. What many people still do not know is that Laika started life as a stray dog. Directors Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter juxtapose archival footage of Laika with footage from the point of view of a stray dog living in Moscow, crafting a poetic imagining of the fable that Laika’s spirit still roams the streets of Moscow.

SPACE DOGS made its world premiere at the Locarno Film Festival and is being released into virtual cinemas in September by Icarus Films. We interviewed Kremser and Peter from their home in Vienna about their fascination with strays, why the space program chose Laika, and how making the film has changed them.

Science & Film: Why did you want to make a film about Laika?

Elsa Kremser: Our first idea was to make a film about a pack of stray dogs, so it was not a story about Laika at first. Then, during research, we found out that Laikaa—the first dog in orbit—was a former stray dog. This moment was really crucial for us: this animal from the street was sent to the stars! This is so absurd that it fascinated us so we went to Moscow for the first time in our lives and looked for stray dogs there.

Courtesy of Icarus Films

S&F: What research was involved in making the film?

EK: It was an intense research period in which we did the important work of finding the right pack that allowed us to follow them. We met plenty of different types of stray dogs—the ones who are really attached to humans and live in garages or at construction areas, and then dogs who are really wild and mate with wolves, who are super shy and live in big packs. We wanted [to film] dogs who are wild but who are still in contact with humans, because we wanted to show wild animals who live between us.

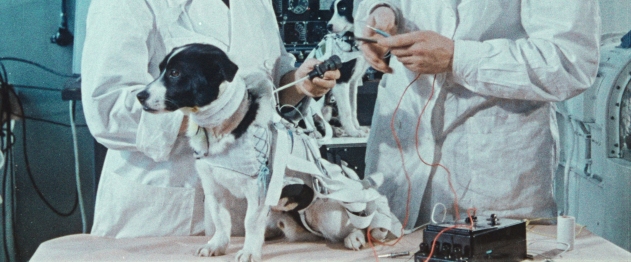

At the same time, we tried to find archival material. We were trying to get information about the whole space program, and we found out that there were actually about 50 dogs sent to space and plenty more in testing facilities. We tried to combine these two stories and layers.

S&F: Why did the space program decide to use stray dogs in the first place?

Levin Peter: This was one of our main questions from the beginning. [They] chose animals who are obviously at the bottom when you think about hierarchy of a city. Still, very often, people see dogs on the streets like they see humans on the streets—for a lot of people it’s kind of the same image; they need to beg for food, they live with insecurity, in harsh circumstances in the middle of the city. [The space program] did start with bred dogs, but they were too sensitive. They weren’t good accepting the loudness of the machines, nor at being in the tiny spaces. When they started to test with stray dogs, they realized that strays are much more used to high stress levels. There was another psychological trick they used: when they caught the stray dogs, they put themselves in the position of a rescuer not a hunter. They provided food, they provided shelter, and they cared for the dogs—all the things that these dogs never had in their lives. Also, stray dogs were cheap, they were all over the city in huge numbers, nobody was missing them, nobody was asking for them. They had no history.

There are a lot of other explanations that we came across in our research. [Ivan] Pavolov [who conducted famous experiments in conditioning behavior] is maybe an explanation [as to why they chose dogs] because the Russians were quite educated in research in dog behavior. Also, they used the image that comes with a dog: a dog is a searching animal, it’s an animal that is always exploring things, using their senses. They used the image of the dog looking towards the sky and sacrificing.

EK: In addition to that, it’s the human’s best friend. They are our companion, and Sputnik means companion in Russian.

S&F: The way you’re describing what these animals went through, it was a pretty tortuous process. It’s not like it’s that different for a human, but in our society going to space is one of the highest achievements. Did making the film make you think about astronauts differently?

EK: We questioned the fact that it’s this heroic thing to fly to space for a human, but a human, if he is in charge it is a decision, so it’s hard to compare.

LP: I remember sitting in this Russian archive for days doing research, when we had to pick from a long list of possible propaganda films which were all dedicated to Yuri Gagarin [a cosmonaut who made the first human trip to space], and we were hoping to find some images of the dogs in these films. We had been watching the same images of Gagarin for hours and hours and I remember thinking of this comparison [between dog and human] a lot relative to the outcome. You come back from space, then what? What is your government doing to you? What is the after-torture?

Gagarin was not very good in the tests, we found out, there were other guys who were better. But he was charismatic, he was beautiful in a way, and he had this average face and strong expression. It was sad to see him after, because he became a symbol. What they did to him, what they professionalized with him, they developed the very early marketing strategies with the dogs then used them on him.

Courtesy of Icarus Films

EK: From looking at his face after the flights, and [seeing the] exploitation of his life, he seemed to us in these images like a broken man. He was put everywhere, but no one was actually interested in what he felt. He was a symbol.

LP: From this archive we learned a lot about what early space exploration meant for the two world-leading nations. You see Moscow full of pure enthusiasm and joy when Gagarin was coming back. We also asked a lot of people who are older and alive then, [and they said that] it was very emotional for them. It gave meaning to all the things that people sacrificed.

In the U.S. at that time it was easy to mobilize people for the sake of their nation. Conquering space was a marketing tool and a mass media experiment and, I don’t know, sometimes the scientific purpose becomes even meaningless when you see the outcome on the planet itself.

S&F: Have you noticed different responses to the film from people in the U.S. and Russia?

EK: We had a festival tour start last summer so we’ve been travelling to plenty of countries, and actually I was expecting more difference country to country. But obviously, the U.S. premiere compared to the Moscow premiere was quite different. In Moscow, it was quite touching because people know so much about Laika. They’ve never seen these images though because the ones we included were never shown before, and they were telling us that they didn’t have any idea that this was true. They knew that it wasn’t just fun for Laika, that she died and it was also torture, but what they saw when they were children was this heroic dog who was happy to go to space. The images in the film and the observations of stray dogs in the street, this turns everything around in their mind.

S&F: How has your relationship to stray dogs changed through making SPACE DOGS?

LP: For two to three years we dedicated all our thoughts towards this lifestyle of stray dogs, but what I appreciated so much was watching them and realized that a lot is up to them: which direction to go, which human to trust or mistrust, where to hide. This made them into real movie characters for us. So I found it hard to watch dogs on a leash when we came back to Vienna. I found myself saying, the dog has its own idea of the ways to go. I totally forgot about this other lifestyle, which is much more dedicated to the will of the human companion.

EK: …The so-called “owner.” This was something which we asked of ourselves a lot: how can you own a living being? To have a dog as a companion felt totally natural, it’s not that we thought that it’s not good to live together, because obviously also the dogs we filmed got really attached to us during all the months of shooting. But to have an owner and rules, and also there is this image of a “good” dog and a “bad” dog…

LP: It’s really weird when we see dogs in Vienna on a leash, and when they are barking to another dog or they want more space, they’re trying to move, and then everybody is saying, this dog is not good. This makes him a bad dog? And a good dog is one who is moving very slowly and is taking care of the movements of the owner? It’s the world upside down, why is this good and bad? For us, during filming the good dog was the one who was moving, that’s what we wanted to show.

Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter, Courtesy of Icarus Films

SPACE DOGS is directed by Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter. It will be available to watch in virtual cinemas starting September 11.

♦

TOPICS