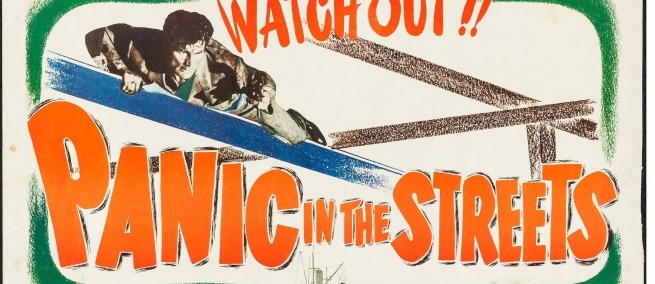

[Editor’s Note: Elia Kazan's 1950 film noir PANIC IN THE STREETS, about an outbreak of pneumonic plague, has newfound resonance in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. Sidney Perkowitz, Candler Professor of Physics Emeritus at Emory University, writes here about the similarities and differences between the efforts to contain the plague depicted in the film and the real-life coronavirus pandemic.]

In the history of film there are depictions of dystopias, such as the world after climate change, giving viewers a safe way to consider potentially awful outcomes for humanity. As we worry about the global crisis of COVID-19 and its unknown future, it’s natural to seek movies that offer insight into pandemics. The list of such films can begin with the classic horror story NOSFERATU (1922), where the vampire Count Orlok, together with rats carrying a plague, bring death to a small, 19th century, German town. Fleas from rats spread the real disease called plague, the cause of the Black Death that killed much of the European populace in the 1300s. Three decades after Nosferatu, the 1950 film PANIC IN THE STREETS brings plague to a big 20th century American city. Plague is not the coronavirus, yet this film shows their shared features and can illuminate issues with the response to our current viral pandemic.

PANIC IN THE STREETS was director Elia Kazan’s sixth feature film, sandwiched between his better-known, Oscar-winning landmarks GENTLEMAN'S AGREEMENT (1947), A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951), and ON THE WATERFRONT (1954)–although it too won an Oscar for Best Motion Picture Story. Shot in black-and-white, noir style, on location in New Orleans, PANIC IN THE STREETS begins with a poker game near the city’s docks. The big winner is Kochak, newly arrived in the city, but he is ill with flu-like symptoms and soon leaves with his winnings. The other players are gangsters and their leader Blackie (Jack Palance in his screen debut) and two of his hoodlums follow Kochak. After Blackie shoots and kills Kochak and takes the money, his henchmen dispose of the body.

When the body is found and the police surgeon examines it, he sees something that makes him call in Dr. Clinton Reed (Richard Widmark) of the uniformed U.S. Public Health Service. Reed finds that the dead man was sick with pneumonic plague, which is easily transmitted between people. Immediately worried that the disease may spread to others in the population, Reed orders the body cremated and inoculates everyone who has been near it with the antibiotic streptomycin.

Richard Widmark as Dr. Clinton Reed

Despite these measures, Reed fears that the murderer and any accomplices are infected and must be found in order to fully control the disease’s outbreak. As he forcefully tells the city’s mayor and other officials, plague is a serious matter. It caused the Black Death and can still bite. In 1924, 26 people in Los Angeles died of pneumonic plague, the most dangerous form that can spread person-to-person “like the common cold…on the breath, sneezes or sputum of the sick.” “I may be an alarmist,” adds Reed, but if plague “ever gets loose it can spread over the entire country.” Plague develops and spreads rapidly, so police have only 48 hours to solve the crime. To deflect blame over not yet doing this, the police chief insists that the victim died by gunshot, not from illness, but then reluctantly assigns police captain Tom Warren (Paul Douglas) to find the murderer.

Dr. Reed’s comments about pneumonic plague could come right from current headlines about COVID-19 and how it is transmitted. Bubonic plague swells the lymph glands and septicemic plague blackens the skin (hence the Black Death), causing high death rates; but pneumonic plague attacks the lungs and is the only form that spreads directly between people. It is 100 percent fatal if not treated quickly, justifying Reed’s urgency in finding infected individuals. It is true too that plague is not gone, even today. Hundreds of cases appear world-wide every year, with occasional clusters as in 1924 Los Angeles, a real event. Fortunately, plague does not come from a virus as does COVID-19, but from the bacterium Yersinia pestis, and can be treated with antibiotics. Reed’s use of streptomycin is valid but would be worthless against the coronavirus.

The reaction to Dr. Reed and his message as he tries to persuade others about the incipient pandemic also has contemporary echoes. The mayor accepts Reed’s expertise but others are skeptical, or like the police chief they act first to defend their own interests. At one point, Reed has to pull rank, forcing the local police to accept preventive injections by threatening to impose quarantine. Captain Warren initially accuses Reed of furthering his own career, but when he sees that Reed really is committed to preventing a medical disaster, he comes to trust the doctor’s integrity and joins forces with him.

Today’s headlines similarly show that some of those in charge blame the messenger who brings bad medical news or are more interested in protecting their own assets than in public health. We also see the tension between broad compliance with pandemic safety guidelines from Federal scientists, and pushback from individuals and local governments unwilling to trust the experts and join a collective response. But we also see selfless actions from medical personnel who, like Dr. Reed, work to save lives even under personal risk. It’s hard not to conclude that a pandemic is a stress test that exposes the extremes of human nature.

PANIC IN THE STREETS depicts the reality that disease does not stop at borders. Even in 1950, when air travel was less extensive than it is today, Reed understands how quickly plague could spread around the world. A port city like New Orleans, where the film is set, is especially vulnerable as we learn when Reed’s investigation uncovers the identity and history of the dead patient zero. Kochak reached the port as a stowaway—carrying both smuggled goods and the illness—aboard a freighter from Oran (significantly, the Algerian city where Albert Camus set his great 1947 novel The Plague about a deadly infestation). With these clues, Warren and Reed find Blackie and his gang members, bring them to justice, and identify the contacts they and Kochak made.

While PANIC IN THE STREETS is a gripping fictional story, the science is real and accurate. The blend of story and science deepens the film’s lessons about pandemics and our response to them. Another lesson comes from the film’s focus on plague, a centuries-old disease that subsides but never completely dies. Whatever the source, once a pandemic is widely rooted in the environment no one can guarantee that it will never reappear. Vigilance is essential.

We must also absorb the message in the film’s final scene. As a tired Dr. Clinton Reed returns to his family, he hears on the radio that “all contacts have been found and inoculated.” We won’t hear that welcome announcement about COVID-19 until testing and contact tracing reach widespread levels and we have a vaccine. Otherwise, we may have our own real panic in the streets.

TOPICS