On January 18, Museum of the Moving Image will open the exhibition Envisioning 2001: Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey, an in-depth exploration of the story, design, and visual effects of the landmark 1968 film 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY–a film that continues to influence, confound, and inspire. With original artifacts from international collections, the Stanley Kubrick Archive, and the Museum’s own collection, Envisioning 2001 explores Kubrick’s influences, research, and innovative production process, and the collaborations that helped him to represent the year 2001 on screen. We sat down with Director of Curatorial Affairs Barbara Miller and Curator-at-Large David Schwartz at Museum of the Moving Image for a preview of the exhibit.

Science & Film: How did this exhibition come about?

Barbara Miller: The show is coming to us from the Deutsches Filminstitut and Filmmuseum in Frankfurt [DFF]; they had assembled a lot of the objects but left it open for us to augment. The bones were in place for an exhibition that emphasized research, design, and the intense collaboration that Kubrick had with scientists in envisioning what the world would look like 35 years from when they started. Our installation is amplifying the groundwork that DFF laid for us.

David Schwartz: The DFF organized the large Stanley Kubrick exhibition that has been traveling around the world for the past decade. This is a more focused exhibition, just on 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, which I was able to see last year when it was in Frankfurt. I thought it was a great fit for the Museum—there is something that’s so unique about 2001, and it’s such an important film on so many levels. The architect Thomas Leeser, who designed the expansion of this museum, was influenced by 2001 so it seemed to really have a home here.

A scene on Space Station 5, featuring red Djinn chairs. Image Courtesy of Warner Bros.

S&F: How did you approach the curatorial process? What story did you want to tell?

DS: It was important to make this exhibition not just a “making of” look at cool tricks and technology. There certainly was a lot of technology invented and employed to make this film, but the reason 2001 captures people’s imaginations is that it has to do with a search for meaning. It’s nothing less ambitious than a film about the history of mankind, and the history of human intelligence. It is a mysterious film. People debate about what it means. The search for meaning and how that ties into Kubrick’s art is something we’re emphasizing in our installation.

BM: By focusing on one film, we can dive into the exploration of these ideas in a thorough way. Diving into the research and design of the film, we are taking those issues on seriously–not just in order to elucidate the film, but also to look at the time in which the film was made. It provides a window into how scientists and designers and writers were engaged in thinking about the future in this very specific way that was historically situated. There was this amazing cross-over between scientists and fantasists at the time that is so rich. Arthur C. Clarke, who was a fantasy writer, was in with the science guys! These people were inventing the future together.

For example, in an early part of the exhibition, we talk about Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke getting together and what they were reading, what they were looking at. We have a copy of Robert Ardrey’s book African Genesis that looks at the theory at the time [in 1961] that human survival was dependent on the apes’ propensity towards violence.

S&F: 2001 was made not long after the Cuban Missile Crisis, at a time when the fragility of human existence was palpable because of the potential of nuclear weapons. Today, 51 years after the film’s release, that fragility and fear of annihilation is still palpable because of climate change and the ways in which humans are propagating their own destruction. Do you think that aspect of the film will resonate in the exhibition?

DS: Yes. Christopher Nolan picked that [theme] up with INTERSTELLAR, a movie that very explicitly refers to 2001 and would not exist without it. The whole story of that film is about climate change. Kubrick originally interviewed a number of scientists for an opening prologue section of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY that was planned. Arthur C. Clarke thought that Kubrick was not explaining enough, that there was a lot in the film that was mysterious and unexplained—which of course is something Kubrick was after. But they battled over that. Reportedly when Clarke first saw the film, he didn’t love it. He felt it was confusing. His novel actually has more explanation.

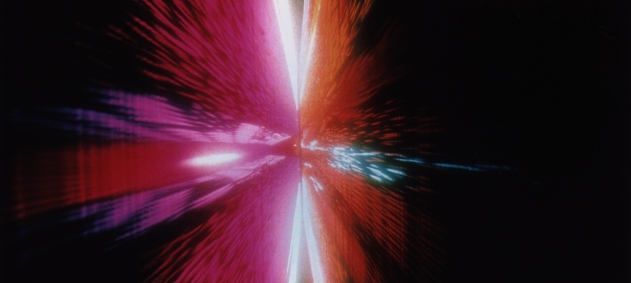

A frame still showing the Star Gate sequence. Image courtesy of Warner Bros.

BM: Their collaboration is so interesting in and of itself, and we get into it a little in the exhibition. The novel 2001: A Space Odyssey was supposed to come out first but the timeline wound up very different than what Clarke anticipated.

DS: After his first films, FEAR AND DESIRE and KILLER’S KISS, which he was unhappy with, Kubrick always worked with existing material. He collaborated with authors, and would always take what he needed and then make a lot of changes. With 2001, the idea that Clarke would write the novel concurrent to the film being made was unique. The film came out in April of 1968 and the book was published two months later.

S&F: In terms of the materials in the exhibition, are there any from the Museum’s collection?

BM: Yes! MoMI has in its collection drawings and correspondence from Graphic Films, which was an LA-based production company founded by Lester Novros, a USC professor, filmmaker, and special effects pioneer. His company generally made films for the military, NASA, and the Air Force, and their work was meant to generate support for the space program. These filmmakers had to invent what space was going to look like. Graphic Films made a film called TO THE MOON AND BEYOND that was in the 1964-65 World’s Fair in Queens, which Kubrick saw. It was directed by Con Pederson. Kubrick was really inspired by it and reached out to Lester Novros in summer of 1965. Kubrick felt so little good work had been done in the sphere of science fiction filmmaking. He loved how Graphic Films was able to visualize space. He asked them to create concept art for the moon landing sequences. So Douglas Trumbull, then in his 20s, drew a lot of sketches providing some of the concept work for 2001.

We have on display a six-page letter from Pederson that is about what you would need to get a nuclear reactor into space—literally, what the scientists said about that. Con Pederson was going to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and talking to scientists and asking how it could be done and translating it into pictures. The two of them, of course, left Graphic Films to work directly with Kubrick on 2001.

S&F: What companies did Kubrick consult with in addition to Graphic Films?

DS: Kubrick consulted about 50 different companies, including commercial companies like Hamilton which makes watches. The exhibition includes a Hamilton watch that was designed for the film. So there was a relationship between commercial companies that were producing fashion and products that helped the film, but then the companies were able to sell these modern-looking products because of the film. Kubrick wanted a look that was not fantastical—the usual thing you see in science fiction movies where everything is made to look exotic. The whole look of 2001 is very clean and minimal, which is one reason it’s aged so well. It is one of the few science fiction spectacle movies that never feels dated. The only things that feel a little dated are some of the brand-name references. Pan Am was the biggest airline in the country at the time and the Orion III space plane is a Pan Am vehicle, but the company went out of business in 1991.

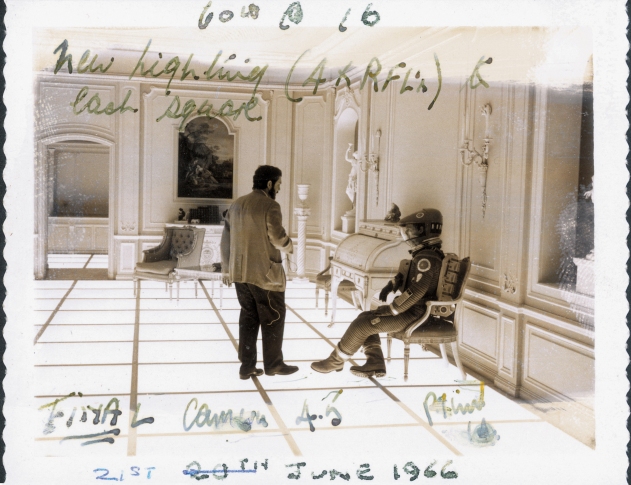

An annotated production still depicting Stanley Kubrick and Keir Dullea on the set of the Hotel Room. Image courtesy of Warner Bros.

S&F: Could each of you tell me about a favorite piece or section from the exhibition?

BM: At the moment, I’m obsessed with two early sections on envisioning space travel and envisioning everyday life. I’m excited about translating how designers, thinkers, and researchers were grappling with the future into the physical space of the gallery.

People in the early to mid 60s were engaged in this idea of researching the future, but even more, they felt like the future is upon us. It sensitized me to what it must have felt like then, which is different than now. The world that generated 2001 is very different from our own. There’s something in the exhibition that really crystallizes that and I’m excited we’re able to include it: it’s a clip of a talk Arthur C. Clarke gave at a press reception shortly before the film opened. He is very eloquent about man’s role in the universe and a quest for meaning, but he puts it in the context of what scientists were doing–searching for extraterrestrial life. Contact with extraterrestrial life is imminent—that’s what Clarke felt. It was a moment in the mid-60s where people felt like inventions that would allow us to engage with space and start planning to go could happen tomorrow. To put the film in that context is exciting for us.

DS: We’re adding a section to the exhibition about how the film was received when it came out, both by critics and fans. The critical response was all over the map. There were critics like Andrew Sarris who panned the film when it came out and then went back to revisit the film because a lot of people told him he was wrong. He wrote another review saying, I was totally wrong, this is a work of genius. But he also said, the second time I saw the film, I was stoned. Famously, it was a film you were supposed to watch when you were stoned. He writes in a funny way in the review, I went back and saw it the right way, and see now it’s a work of genius. We also have a few fan letters. A young woman from Queens wrote a complaint letter to Kubrick saying, I don’t know what this means.

The film was marketed as “The Ultimate Trip.” Part of the trip is this trip to space, to Jupiter and beyond, so the film is about that trip, but the film itself is the ultimate trip. What Kubrick did, the cinematic achievement and experience, there’s almost no dialogue in the film, it’s a totally immersive cinema experience. The viewer goes on a journey and it opens up your mind, culminating in this abstract Stargate sequence. On the journey through experiencing the film you get these feelings that Barbara’s talking about, about where the human race is going. It seemed like the year 2000 was going to be this major turning point. Of course, it didn’t turn out exactly the way people envisioned at the time. But that seemed like an important landmark; we were about to land on the moon. It’s a sad irony that Kubrick didn’t make it to 2000; he died in 1999.

Envisioning 2001: Stanley Kubrick's Space Odyssey opens at the Museum of the Moving Image on January 18 and will be on view through July 19. Tickets to a private exhibition preview, and 70mm screening of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY and discussion with stars Keir Dullea and Dan Richter as well as Katharina Kubrick, are now available. In conjunction with the exhibition the Museum will present a number of film series including Influencing the Odyssey: Films that Inspired Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, curated by David Schwartz, and the Science on Screen series Outer Space Speculators which pairs films that offer speculative visions of outer space grounded in scientific research of their time with introductions by scientists.

Cover image: Stanley Kubrick on the set of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968). Courtesy of Warner Bros.

TOPICS