An interactive, virtual reality (VR) piece called LUX SINE will have its world premiere at the 15thannual Camden International Film Festival, which takes place in Maine from September 12-15. Set in the Black Hills of South Dakota, LUX SINE leads users through two subterranean tunnels, one of which is used by particle physicists who are part of the Stanford Underground Research Facility and the other of which is part of the Lakota people’s creation story. LUX SINE’S director Alex Suber spoke with us in Brooklyn before the piece’s world premiere.

Science & Film: How did you first come to the Black Hills of South Dakota?

Alex Suber: I was led into this world by an author named Kent Meyers who wrote an article called “The Quietest Place in the Universe” which is about the conception of the Sanford Underground Research Facility and the people who came before [it was established]—all the way from General Custer and the tribes that occupied that land and still do to this experiment called LUX (Large Underground Xenon experiment). Our crew spent two months in the region and was fortunate enough to meet a lot of different stakeholders in the community, at the Stanford Research Facility in the Homestake Gold Mine and also in Wind Cave which holds the origin story of the Lakota. We met a young woman named Shine Bear Eagle who took us into the cave, turned off all the lights, and told us the origin story over 30 minutes. That sent us on the journey of using different technologies to recreate the sense of wonder we experienced first visiting those two different places.

S&F: What do these various stakeholders think of each other?

AS: I think that showing the piece in context, in the Black Hills, will answer that question more fully than I could.

S&F: Is that the plan?

AS: Yes. I talked with the Stanford lab today and we’re going to do a talk and demo there. I have also been in touch with different members of the Lakota community and I hope that they’ll all come together at this talk at the laboratory and we’ll be able to facilitate a conversation between spirituality and science. That’s the dialogue that I want to emerge. These two worlds seem to be on parallel tracks in many ways—asking similar questions—but they’re not in conversation.

S&F: Some people think that science and spirituality are two sides of the same coin, others see them as opposites. How did LUX SINE affect the way you consider these perspectives?

AS: I think that spirituality and science are intermingled, and are two sides of the same coin. Often time they talk past each other, but in many ways they’re seeking similar answers to what lies beyond. The means are very different, but I do think that when you examine the language and step back, a lot of times there is a lot of agreement. The structure of LUX SINE as a diptych—in one sense the cave and in one sense the laboratory—was very deliberate. I didn’t tie them together explicitly but rather left the viewer to weave that story. Considering it’s virtual reality, interactive, and multi-branched, each person will gravitate towards the part of the story that resonates most.

S&F: Did you experience any boundaries between the scientists and members of the indigenous community when making LUX SINE?

AS: I did experience some of the scientists rebuffing some of my questions, or reframing them. On the other hand, some of the members of the Lakota tribe were quick to point out that scientists had discounted their viewpoints. For example, there was a visitor who got lost in the cave and, long story short, she emerged after a few days and said that she was guided out of the cave. She said she followed little lights, friendly entities, and knew she would get out. People told her, you were dehydrated, your brain was filling in things and playing tricks on you. I think she became a very spiritual person after that. The scientists wrote it off and the Lakota people who have been leaving blessings there said oh of course, those are the spirits.

S&F: Technologically, can you tell me how you made LUX SINE? When did you start thinking about what experience you wanted a viewer to have?

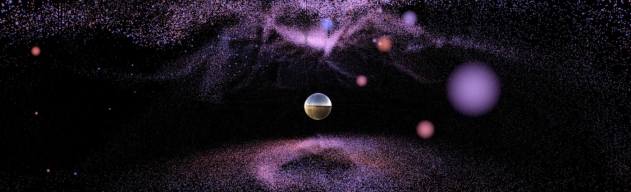

AS: I come from a traditional documentary filmmaking background so I’m used to a frame, a linear timeline, certain advantages of lensing, and keeping people’s attention. But I’ve been working in virtual reality for a few years and something I really like about it is the ability for the technology to uniquely reflect the content of the work. So I carefully chose a few different pieces of technology that allowed LUX SINE to be fully interactive and also to reflect the nature of this dark place beyond what humans can see. The first piece of tech was the 360 camera. We worked with Google on a prototype camera they had called the Odyssey—which they killed recently. We used that to create video to give you a sense of presence in the photo-real space, because it is quite a magnificent old heritage of gold mining. The other main piece of tech is a LiDAR scanner, which is like a laser scanner that senses depth in space. The final piece of tech is called Depthkit which is a form of volumetric video which creates 3D avatars of the people. It allows you to place them in a 3D space and do some visual effects work which you wouldn’t be able to do with a regular 3D camera. We interviewed everyone above ground for ease of use and then in postproduction, instead of building this in a non-linear editor, we did most of the work in a Unity game engine. The piece is very much created in postproduction in the fashion of a videogame, but the capture and production stage is very much akin to filmmaking.

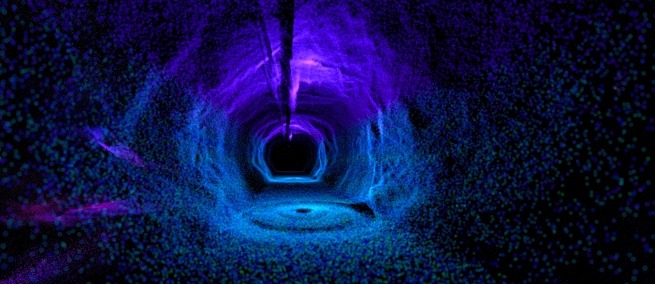

S&F: You said that you are interested in how technology can reflect the story. How does it do so in this case?

AS: This is a geospatial story. The act of just being there is part of what you take away. The cave and lab are both very difficult and risky to get to—you might never be able to get to them. In terms of the medium reflecting the form, the biggest [way it did so] was the LiDAR scanner. The LiDAR scanner is a laser that you can’t see, that captures a sense of space that your mind can’t perceive. Its point-cloud aesthetic helped to convey a sense of what lies beyond, this otherworldly consciousness of the space.

Shooting a virtual reality documentary in a place that has less exposure to technology than, say, NYC, was also really interesting because along the way we would show someone what it was like and they had never done VR. It was a cool and curious encounter. We have plans to go back. I’m really curious to see how people react both to the technology and to their likeness in the technology—it’s very strange to meet yourself in 3D.

LUX SINE will have its world premiere at the Camden International Film Festival, which runs September 12-15.

TOPICS