Unsuspecting citizens drive across a frozen Lake Baikal that abruptly cracks underneath their car, sinking it, at the start of Russian filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky’s new documentary AQUARELA. The ice in Russia is melting three weeks early. Kossakovsky captures, at a detailed 96 frames-per-second (fps), the beautiful and brutal nature of water. In Greenland, ice masses break the ocean’s surface and tumble menacingly. Rain during Hurricane Irma floods Ocean Drive. Venezuela’s waterfall Angel Falls cruises down a mountain with a force that could kill. To film in these conditions, and at 96 fps (rather than the traditional 24 fps), Kossakovsky had to invent a number of engineering and technological solutions. On August 12, the Museum of the Moving Image presented a preview screening of AQUARELA with Kossakovsky in person, the week before the film’s release into select theaters by Sony Pictures Classic. Below are excerpts from the conversation between Kossakovsky and film critic Alissa Wilkinson.

About filming at 96fps:

Victor Kossakovsky: Normally in cinema if it rains, you see white stripes. In this film, you see every drop separately. […]

Alissa Wilkinson: A lot of film has been constrained by things [standards] that were developed decades and decades ago and never changed.

VK: Sound appears, color appears, Dolby appears, digital cinema came, now Atmos sound, and we still stupidly stay in 24 fps. Every day you’re watching 1,000 fps in football; when they screen beer commercials, those are filmed at 1,000 fps. To film a fast frame rate you can do it, but to film and to screen at the same frame rate, this is the story. And actually there is no technical limit to this, just because no one has done it, that is why it’s technically complicated. Even on the computer there is no editing program for 96 fps, so we invented all this.

Photo by Aleksandr Dudarev

About filming AQUARELA:

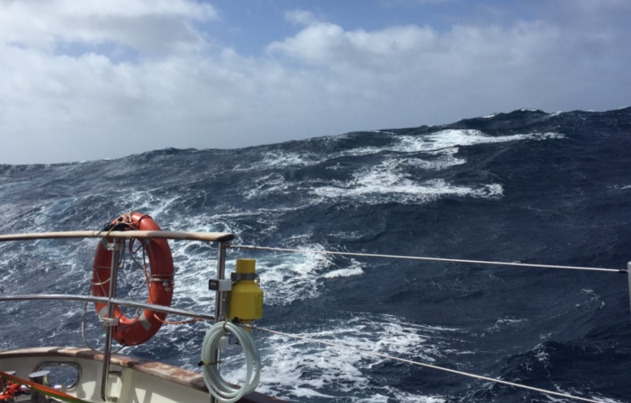

VK: We did not plan to have such a risky movie, of course. No one will insure it if you plan it. […] Have you ever been in storm with waves like 20 meters high? I can tell you. Suddenly, this chair will just fly there [gestures across the stage]. […] We wanted to go from Portugal to Greenland—I wanted to catch a storm. When we came to the storm, it was so strong that we were not able to get out. The storm brought us to Canada instead of to Greenland, and we were not able to go out for three weeks. […]

Audience: How did you manage to get those sequences in the middle of the ocean, with those waves, and survive?

VK: The first week, you cannot film because you just want not to die. You’re afraid and you’re vomiting. There is no camera, there is no film, you just say, fuck, and you rope yourself around the mast and whatever happens… The second week, you want to die. You’re so exhausted you cannot even think anymore. You say, I cannot, I’m done. Just to finish it. But this is not the end of the story. The most difficult is the next week, because you realize that you are not going to die! You have to take it. This is the one moment when you have to start filming. But, the question is more interesting in terms of cinema. This was the reason why I came to make this movie.

Every time you saw the ocean before this film, it was made in a studio. Normally it’s a huge aquarium or swimming pool which is moving, and with light and effects and special lenses you feel like you are in a storm. But in fact, you are just comfortable drinking coffee and [smoking] cigarettes [laughs]. So I said to myself, there must be a way to make it real and to get emotion. Of course you can affix the camera to the boat and the boat will be jumping and it will be quite emotional, but you will not see water. My goal was to see water, how it looks in these conditions. When waves are 20 meters, what it looks like. This was the biggest challenge. We had to make it in a way that no one would understand how we did it. You cannot use a drone there because the drone will simply fly away like a mosquito. Helicopters cannot be there in the middle of the ocean, there is no way, after like 30 knot winds they cannot fly. I was checking Leonardo DaVinci drawings [laughs]. I swear. He had great ideas about this. His idea was that you have to shoot [a gun] from the boat if there are waves. So imagine a military boat and they have a gun, not to film but to shoot. […] Militaries shoot during the war in the ocean and they must be sure that the bullet flies in the direction that they need. So I started digging in that direction. I found someone who understood and was able to adapt military technology for huge guns to the camera needs.

Photo by Charlotte Hailstone

How the film changed his perspective on the world:

VK: We overestimate our place in the world. We believe we are the most important. And after this film, I definitely disagree with this idea. When you go into the ocean, there are islands of plastic the size of England. They are becoming bigger—almost the size of Australia—in the Indian Ocean. I remember the moment when the first plastic was invented: we were happy. If you think more about it, I am coming to the idea that we have to understand this world first before we change it. We use everything for ourselves; we kill animals, we cut trees, we do everything we want.

It happened that at the same time I was filming [AQUARELA] I was filming a movie about a pig, chicken, and cow—also no voiceover, no narration, no people, no slaughtering, no concentration camp for animals, just animals how they are. Before I started filming water I was talking with scientists about everything. They know nothing. The more studies, the more convinced they are that they know less and less. Same with animals—the more they study, the more surprised they are that they know less and less.

I have a long table. On the left side was my research about AQUARELA, on the right side was my research for my film about animals. Each scientist has figures and numbers, but they don’t know what each other knows, and I put it on one table and I was shocked. At the moment on the planet, 1.5 billion people have no access to water. At the same time, we have two billion pigs, almost two billion cows, and twenty billion chickens. Each cow needs 30 times more water than a human. We don’t have water for humans, but we have water for almost four billion big animals who need 30 times more water than we do. We’re cutting trees everywhere and when we cut trees we make the land dry, because trees produce rain. It’s totally absurd. It’s everything for us, for our comfort. I guess we need to be a little bit more modest and say okay, we need to find our place in the balance with everyone else, not just everything for us. Because these animals live on average four months. Can you imagine?

Photo by Charlotte Hailstone

AQUARELA opened in New York and Los Angeles on August 16, with additional cities across the United States following. Where the technical ability exists, the film is projected at its intended 96 fps. AQUARELA is an international co-production that received support from Participant Media, the BFI Film Fund, Creative Scotland, the Sundance Institute, and more. Kossakovsky wrote, directed, edited, and filmed the movie. Ben Bernhard was also cinematographer. It was co-edited by Molly Malene Stensgaard and Ainara Vera. Aimara Reques was co-writer. Eicca Toppinen did the film’s music, which is largely heavy metal.

Cover photo by Victor Kossakovsky and Ben Bernhard

TOPICS