National Geographic’s new feature-length documentary APOLLO: MISSIONS TO THE MOON celebrates the 50th anniversary of the first manned lunar landing by considering the scope of NASA’s Apollo missions. Project Apollo began in 1966 and ended with Apollo 17 in 1972. Directed by Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Tom Jennings, the film is comprised entirely of archival footage. It premiered on National Geographic Channel on July 7 and is now available for streaming. We interviewed Jennings together with astronaut Mike Massimino who has spent over three weeks in space on two shuttle missions.

Science & Film: This film is different than other films about missions to the moon in that it looks at the full scope of Project Apollo. Tom, how did you decide that this is how you would tell the story?

Tom Jennings: Anniversaries are great for television, the press loves to cover them and rightly so. This one is one of the biggest anniversaries of our lifetime, and we decided to make it different by doing all the missions so there was context to 11.

We started talking with National Geographic Channel in August of 2017 about doing something for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. I’ve done a lot of these kind of programs with no narration, with archives, which I really love doing because I think if you do it right there’s a magic to it that you don’t get with other forms of non-fiction storytelling. National Geographic really wanted my company to do something for the moon landing. My only concern early on was, knowing that it was such a huge anniversary, that there would be a dozen if not more similar programs—rightly so, because the moon landing is perhaps the greatest human achievement, certainly of the 20th century. So we talked with them about how we could make our film different. Almost within the first week of the discussions we said, one way to make it different would be to do all of [the missions]. Everybody’s going to be doing 11 because it is the anniversary, but 11 doesn’t exist in a vacuum; 11 is the culmination of everything that came before, and missions that came after benefited from what 11 had done. All 12 manned missions, and mentioning all the other missions, we also have to live in the real world where we’re relegated to the clock of broadcast television, so we had to find a way to whittle down the story to the most important moments, which I believe we did.

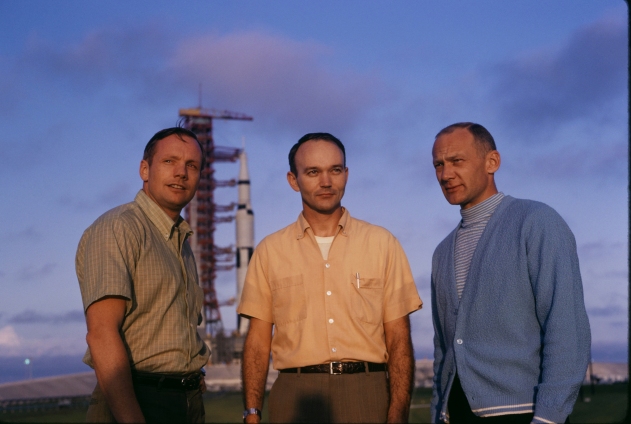

Apollo 11 astronauts Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin, Jr. stand near their spacecraft. (copyright OTIS IMBODEN/National Geographic Creative)

S&F: Mike, what was it like for you leaving for space? Did any of that footage from the film resonate with your own experience?

MM: Yeah. I was a civilian, I have never been in the military, so for me it was a new experience to face an event that might be life-changing in a bad way. You’re very excited about doing it, but there’s always a chance of something bad happening. It made me try to appreciate the time I had with my family leading up to the launch and after. I missed them very much and looked forward to getting back. But it does take a toll. These are normal families and relationships that are put into an extraordinary situation. It’s also out there in the public. [The mission I was on] wasn’t a huge media event so I think it was much more difficult for those families [from Apollo 11] to deal with, because they weren’t just dealing with this very dangerous situation that could potentially not go well, but also that it was going to be live broadcast.

S&F: There’s a moment when a television interviewer asks Jan, Neil Armstrong’s wife, what she and Neil are going to do when he gets home and she replies, he has to get home first.

TJ: I’m glad you pointed that out because one way we wrestled this thing to the ground with so much story was that we created groupings of characters, much like a feature would do. The astronauts were a character—we couldn’t focus on just one because we were covering all the missions; the wives and the families were also a character and we would follow very traditional heroes’ journey story arcs; people in mission control; we even made the spacecraft a character; and the American public. We had each [character] mapped out on a wall and we could then understand where we were in the story. It was chronological but if you really analyze how the story ebbs and flows, it is designed with great purpose. I think that sets the film apart from some of the other ones. Using just the footage we had to nail all these stories and make them weave together.

Mike Collins and Valerie Anders (wife of astronaut Bill Anders) in Mission Control. (copyright Joe Scherschel/National Geographic Creative).

S&F: There’s a quote in the film about how teamwork is the most important part of going to space. Mike, on your spaceflight who was that team?

MM: The team is huge. One of the Apollo astronauts told our astronauts that they felt like they were being asked to do the impossible and that we were going to be asked to do the impossible in our careers and that the only way to do that is through teamwork. He told us to find a way to care for and admire everyone you work with. If you find someone you don’t like on your team, it’s not that you don’t like them, just that you don’t know them well enough.

You have to have different ways to approach problems. It was a varied group of people: the crew, our instructors, the flight controllers who cared for us while we were in space, the divers at the pool who got us ready to spacewalk, the secretaries in the office, the people who worked in cooking, and the people who launched us. It’s a huge team. You mentioned families before. That’s definitely part of the team as well. I think they all felt that sense of pride. You have to hold up your end of the bargain in order not to let the team down. That’s what we felt during our shuttle missions. Of course the Apollo astronauts felt that same way with the Apollo missions. It makes NASA a great place to work.

S&F: Tom, in terms of making this film, who were the essential people?

TJ: We don’t have tens of thousands of people working for us, but the goal is the same [as that which Mike just described]: to do something really extraordinary, to be the best at it, and to create something that will last forever. We feel like we’ve created a film that you could show 20 or 50 years from now and it’s going to hold up because those events don’t change. We had a team of about four to six researchers at any given time. We had a key editor who edits most of my films, David Tillman, and he is brilliant at taking raw footage from multiple sources and turning them into what feels like a scene from a movie. We had a supervising producer and a couple of story producers.

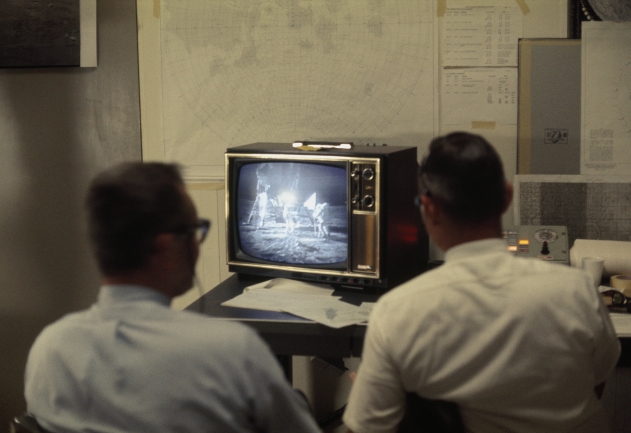

Technicians watch a live television transmission of man walking on the moon. (copyright Otis Imboden/National Geographic Creative)

S&F: What were the major historical moments that you knew you had to include?

TJ: You can’t do the Apollo mission to the moon without Apollo 13, or Apollo 11, or the fire in Apollo 1. We made sure we had images and sound that could tell those stories and fortunately there was a lot from which to choose. Then we would look for the happy accidents along the way. One of my favorites is the crew of Apollo 7 on the Bob Hope Show. Apollo 7 got tucked into the show because it was the first live television broadcast [from space].

S&F: The role of moving images in the history of space missions is in and of itself super interesting.

TJ: I can tell you a quick aside about something that didn’t get in. During Apollo 12, they pointed the camera at the sun. Within five minutes of bringing it out they fried it, so they didn’t have moving images. So, two of the three major networks got actors dressed up like astronauts on a sound stage. I think this is where a lot of the moon landing conspiracy people got their thing. Because the broadcast would say simulation, and they would listen to the audio that was being pumped back from the moon and then the actors dressed like the astronauts would kind of hop around. It’s hilarious stuff. My favorite [part] is that NBC went with a guy named Bill Baird who was a puppeteer. He did marionettes for THE SOUND OF MUSIC, the lonely goat heard scene, and they hired him to make puppets of the astronauts. NBC can’t find that footage but we went to the Bill Baird Museum is Mason City, Iowa and they had a small clip of the footage. We were all so in love with it but wound up cutting it and the reason was, there is so much great NASA stuff and that moment was part of the media story and not as much part of the Apollo story. So we said goodbye to the Apollo 12 reenactment. It was a heartbreak.

APOLLO: MISSIONS TO THE MOON is available to watch on National Geographic online.

cover image: Lunar module assembled at Grumman. Public Domain.

TOPICS