Carl Akeley had, from today’s perspective, a complex relationship with animals. He shot, as in killed, hundreds. He shot, as in filmed, the first footage of mountain gorillas. He preserved and presented scores of animals in the most prominent natural history museums in the world.

The Field Museum in Chicago just opened an exhibition, “Mr. Akeley’s Movie Camera,” that presents Carl Akeley (1864–1926) as an inventor. His goal was always to present truth in nature. Acknowledged as the founder of modern taxidermy techniques, Akeley had an auspicious start to his career when he was tasked with preserving P.T. Barnum’s star elephant Jumbo. Akeley was apprenticed at Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York. The shop’s owner, taxidermist Henry Ward, was the expert Barnum turned to when Jumbo died in 1885, and Akeley was there to help. Foreshadowing his later technical innovativeness, he “turned to bent wood and iron to support the hide, and a touch of paint completed the illusion. He then structured the skeleton so that it could travel easily; the skull was detachable and the rib cage and spinal column could be removed and replaced by any roustabout,” writes Rebecca Chace in the January 20, 2016 issue of the Los Angeles Review of Books. These skills enabled Akeley to gain employment as a taxidermist first at the Milwaukee Public Museum and then at the Field Museum where, in 1896, he became their first Chief Taxidermist.

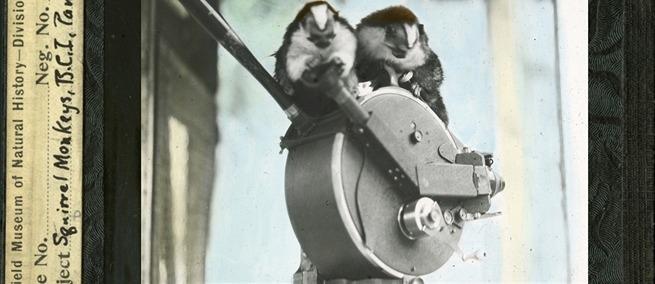

Close-up of a movie camera invented and patented in 1915 by Carl Akeley. Nicknamed the “pancake camera” because of its flat round profile, it was a highly maneuverable and portable device designed to capture footage of animals in the wild. © John Weinstein, Field Museum.

Carl Akeley innovated various processes, including the use of hollow clay and papier-mâché, that allowed his taxidermied animals to appear more life-like than ever before. Chace, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, explains how Akeley’s animals were different because “the mold was made to fit the hide from inside out, rather than the hide being stretched over an armature that only approximated […] the animal.” When Akeley taxidermied animals, they retained their dimensions and even their musculature.

At the Field Museum, Carl Akeley’s best-known work is the sculpture of majestic fighting elephants in Stanley Field Hall. His work garnered attention, and in 1909 he moved to the American Museum of Natural Historyat the invitation of its president Henry Fairfield Osborn. There, his major legacy is the Akeley Hall of African Mammals featuring 28 habitat dioramas. Akeley’s goal with his dioramas, as with his sculptures, was to render “as faithfully and accurately as possible the three-dimensional forms of nature, life, and even movement,” as Mark Alvey, an Akeley scholar from the Field Museum who advised on the current exhibition, writes in his 2007 essay “Akeley, Cinema as Taxidermy.”

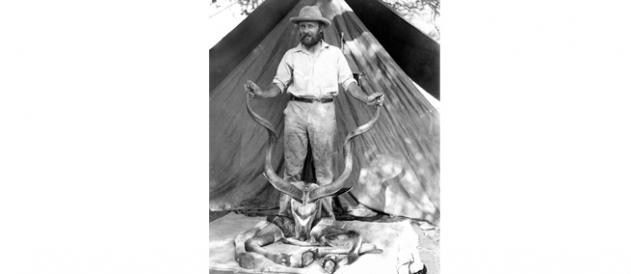

Carl Akeley posed with skull, horns, and hoofs of an antelope during his 1896 Africa expedition. © Field Museum, CSZ6167.

Historian of science Donna Haraway has written about “nature’s truth” with a degree of irony, particularly in her essay “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1938,” first published in the journal Social Text in 1984. “Akeley's concentration on finding the typical specimen, group, or scene cannot be overemphasized. But how could he know what was typical, or that such a state of being existed? This problem has been fundamental in the history of biology; one effort at solution is embodied in African Hall,” (p. 36). Akeley had a concept of perfection and beauty that he looked for in animals (large, symmetrical). His displays placed males in the center, and included at least one animal who looks out to make eye contact with a human visitor.

His quest for truth in nature continued from hunting and taxidermy to filmmaking. Akeley first took a motion-picture camera to Africa on an expedition for the American Museum of Natural History in 1909. He wanted to film a lion hunt. He had with him an English-made Urban camera, according to Mark Alvey’s 2007 article, but was dissatisfied with what he was able to shoot. As he wrote in his 1923 autobiography In Brightest Africa, “the native hunters had drawn a lion’s charge and killed the lion with their spears. But the opportunity had been as short-lived as it was magnificent, and the kind of camera I had then could not be handled quickly enough. As I walked back to camp that night, I was determined to make a naturalist’s moving-picture camera which would prevent my missing such a chance if ever such a one came my way again. From 1910 to 1916 I worked on this camera whenever I had a minute to spare” (p. 223).

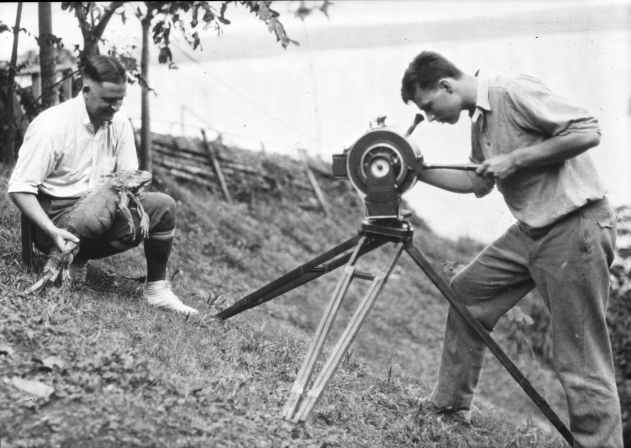

Akeley formed the Akeley Camera Company in New York in 1911 and patented the Akeley Motion Picture Camera in 1915. His invention was dubbed the “pancake” camera because it is circular. The tripod he invented for the camera differs significantly from previous technologies because it is gyroscopically controlled, so that the cameraman can pan and tilt the camera fluidly, all the better to capture animals moving at fast speeds. Before the pancake camera, tripod heads had to be unscrewed to move the camera. Akeley’s camera was also comparatively lightweight, so could be used in the field. It performed well in low light; the shutter had a 230 degree opening that admitted about 30% more light, according to Alvey (p. 32). It could also be reloaded with film stock more quickly. The camera’s design was modeled in part on a turret-mounted machine gun.

The pancake camera was promoted by Akeley for nature filmmaking, but it was quickly appropriated by others tasked with shooting in challenging conditions such as news cameramen, for aerial reconnaissance by the U.S. Army during World War I, and by Hollywood film studios for capturing action shots.

An Akeley motion picture camera was used during the Field Museum’s 1928-29 Crane Pacific Expedition. Explorer Karl Schmidt holds a green iguana, Sidney Shurcliff operates the Akeley camera. © Field Museum, Z93018.

Akeley himself tried to shoot with his camera. On an American Museum of Natural History expedition to present-day Zaire in 1921 and ’22, he filmed MEANDERING IN AFRICA with footage of mountain gorillas that had never before been captured on film. He went on to commission two filmmakers, Martin and Osa Johnson, to use his camera to shoot animals in Africa in order to help raise funds for his proposed Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History. They set up a special corporation to fund the Johnsons’ filmmaking. Their first collaborative project was the film SIMBA, KING OF BEASTS, which included the lion-spearing footage about which Akeley had once fantasized capturing. The short film opened in 1928 at the Earl Carroll movie theater in New York, and earned $2 million at the box office. After that, the Johnsons continued to use Akeley cameras to make some of the first nature films. The pioneering documentarian Robert Flaherty used two Akeley cameras to shoot his 1922 film NANOOK OF THE NORTH in the Canadian Arctic.

“Mr. Akeley’s Movie Camera” at the Field Museum features a newly acquired Akeley camera and tripod. Based on historical records and an inscribed signature, the Field Museum asserts that it once belonged to Hollywood filmmaker Elmer Dryer. Dryer was a cinematographer, and is noted for being the first cameraman to specialize in aerial photography. He was nominated for an Oscar for his work in Howard Hawks’ AIR FORCE, and also worked on Hawks’ ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS, and Howard Hughes’ HELL’S ANGELS, among many other noteworthy productions. “Mr. Akeley’s Movie Camera” also features some of Akeley’s taxidermy work, such as a young mountain sheep, as well as footage from SIMBA (1928).

“Mr. Akeley’s Movie Camera" is on view at the Field Museum through March 17, 2019. The Museum of the Moving Image also has an Akeley pancake camera on display in the permanent exhibition “Behind the Screen.” This particular camera was used by Dennis Bossone, a cameraman for Fox Movietone News, in the 1930s.

Cover Image: Squirrel monkeys sitting on top of an Akeley movie camera during the Field Museum’s 1928-29 Pacific expedition in Panama’s Barro Colorado Island. © Field Museum, GN92153_1801d, Photographer Karl P. Schmidt.