[Editor’s Note: Chiara Atik’s new play BUMP premiered at the Ensemble Studio Theatre (EST) as part of its annual First Light Festival, showcasing new plays that feature science or technology themes supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Atik received Sloan-support to develop the play. The EST production of BUMP ran from May to June 2018, directed by Claudia Weil (GIRLFRIENDS). Following the June 2 matinee, our executive editor Sonia Epstein moderated a discussion between Atik, Weil, and experts including Jorge Odón, whose birthing device inspired the play. Scenes from the play were subsequently staged at the U.S. Agency for International Development’s annual “Saving Lives at Birth” event in DC. The following article was first published in a slightly different form on the EST blog, and is republished here with permission.]

An amazing thing happened during the last weekend run of BUMP, the new comedy by Chiara Atik that was this year’s EST/Sloan Mainstage Production. The idea for the play began when Chiara discovered the story of Jorge Odón, an Argentine garage mechanic who saw a YouTube video about a cork getting removed from a wine bottle—and that video inspired him to invent a revolutionary new device to help in the late stages of childbirth delivery. A fictionalized version of Odón’s story became, in Chiara’s hands, one of three storylines in BUMP. Odón still lives in Argentina but on Thursday, May 31, three days before the play was due to close, the EST office got a call that Jorge Odón himself was flying in to attend the Saturday matinee performance and yes, he would be happy to participate in a talkback after the performance. Odón and his wife Marcella arrived with Mario Merialdi, the World Health Organization executive who was critical in helping Odón turn his idea into a product that has gone on to be clinically tested in Iowa, South Africa, and Argentina and may start going into use in 2020.

Joining Odón and Mario Merialdi for this remarkable talkback on June 2 was the playwright Chiara Atik, the director Claudia Weill, translator Rosa Rivera, and David Milestone, the Acting Director of the USAID’s Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact, an organization that also played a key role in funding the development of the Odón device. Sonia Shechet Epstein, Executive Editor of Sloan Science & Film at the Museum of the Moving Image, moderated the discussion.

A lively comedy about childbirth, BUMP explores women’s evolving understanding of and control over the birthing process through three stories: a young first-time mother giving birth in colonial New England with the help of an experienced and peppery midwife; five women sharing quips, gripes and observations on an online message board; and a grandfather-to-be getting inspired to invent a device that could revolutionize how infants in difficulty get delivered (this is the storyline inspired by the experiences of Jorge Odón).

Some of the highlights of the June 2 discussion follow: (Recap by Rich Kelley)

Sonia Epstein: Chiara, in BUMP there are characters who give birth in a range of ways. Why was it important for you to present that range?

Chiara Atik: The play is not trying to say that there is a correct or incorrect way to give birth. My hope was that by offering an assortment of examples of what giving birth is like, that the audience could take what it wants from the different experiences. The play ends with the colonial girl looking at her future. That’s where I wanted the focus to be.

Left to right: Sonia Epstein, Chiara Atik, Claudia Weill, Jorge Odon, Mario Marialdi, Rosa Rivera, David Milestone. Photo by Rich Kelley.

What Jorge Odón thought after seeing BUMP

Sonia: Jorge, what is your reaction to seeing your invention dramatized?

Jorge (translated by Mario Merialdi): The play is great and he is still surprised about his invention and how it has been interpreted. . . . This invention actually took him around the world to meet many important people. He met Princess Caroline in Monaco. He met Pope Francis. The device got on the front page of The New York Times. Seeing this play was really a surprise for him.

When he was seeing the play he could see and feel very much of what had happened in reality. He was spending hours on this device. His wife Marcella, who is here with him today, actually did sew parts of it. He congratulates Chiara and all the actors who interpreted his story.

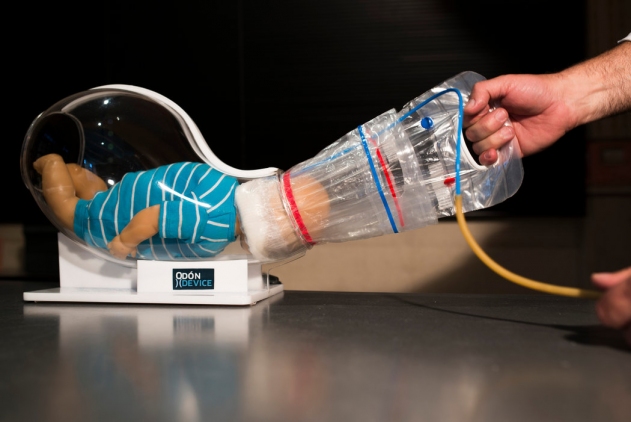

Sonia: And what did you bring with you today?

Jorge (translated by Mario): [shows prototype for Odón device] This is a simulator of the uterus that he uses for demonstrations of the Odón device. The first prototype of the device is what he is showing here. He’s a car mechanic. He’s not a doctor. He needed to learn how the baby exists inside the uterus. This part was used the first time to insert the device. It was difficult for the doctor to use it and to position the device correctly. This is the inserter. The gauge indicates when the device has been inserted properly.

It’s been fourteen years since he had the original idea. This is the bag we use now. Now he is going to fill it with air. This is not hard to do. The device immediately deflates once the baby is removed. You have now seen in just a few minutes the evolution of the device over fourteen years. Imagine what happened in between. Jorge was actually very afraid of seeing blood. Because of his passion, he was able to attend 48 deliveries. In these 48 deliveries he was able to deploy the device. Without the help of his family, his friends, and everyone who believed in him, he would not have been able to develop the device. Without them it would not have been possible for a big company like Becton Dickinson to pick up his idea and take it to the next level. It first was his family that supported him, then it was CEMIC, the Center for Medical Education and Clinical Research in Buenos Aires; then it was me [Mario Merialdi] who was shown this device and fifteen weeks later Jorge and I were together in a hospital in Des Moines, Iowa, a very specialized advanced center testing the device.

How the Odón device went from an idea to a product

Sonia: Mario, you’ve been instrumental in the development of Jorge’s device. I’m curious about two things: first, what about the Odón device stood out for you when you first saw it and second, how aware were you of the need for innovation in obstetrics before the device?

Mario: Someone mentioned in the play that there had been no innovation in the instruments used for childbirth deliveries for centuries. There was definitely a gap there. I remember I was working at the time at the World Health Organization. I was leaving to go from Geneva to Buenos Aires for a meeting. I got a call in the evening from a colleague in Argentina telling me about a crazy doctor at a hospital working with an even crazier mechanic who had a new device for assisted vaginal delivery. I was very skeptical but at the same time I was intrigued because of the unmet need for new devices both in developed and developing countries. So I said I will be at this meeting and will be able to give him ten minutes. I met with Jorge who showed me the device. The moment I saw that this was something new in the field I was intrigued. The reason why it’s so appealing is that forceps and suction are all lifesaving procedures but they require professionals and they are not available everywhere in the world, especially in the area where most of the world lives. Seeing this device that is potentially easier to use and potentially safer was very, very promising and pushed me to invest and to develop a research plan.

How USAID innovates new medical solutions, and helped develop the Odón device

Sonia: David, I know that you and USAID also helped develop the device. What are some of the criteria you were using to decide which innovations to support?

David Milestone: I’m with the Global Health Bureau of the US Agency for International Development, the part of the State department that works on economic development and humanitarian assistance primarily in places with low resources. Think Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia. We’ve made a lot of progress in global health. For example, we cut child mortality in half in the last few decades. We still have a long way to go to reach what we call sustainable development goals that the United Nations targets around maternal newborn mortality. One of the things we recognize is that we need to start working and thinking in different ways if we’re going to have any chance of reaching those targets. Part of that is casting a wider net to different nontraditional problem solvers.

Over the last several years we’ve run programs called “Grand Challenges,” which are open innovation competitions around maternal and newborn health, like Saving Lives at Birth, and around the Ebola and Zika grand challenges to help us be better prepared for the next outbreak. [Note: The Odón device received funding in Round 5 of the Saving Lives at Birth challenge in 2015]. What we’ve found is that great ideas can come from anywhere, from Buenos Aires to just up the street at Columbia University where a group of students developed a type of colorized bleach to be used in decontamination settings during the Ebola outbreak in Liberia. It’s now being used in the current outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. What’s exciting about that is that was a group of students at Columbia. They now have a business, they’re making money and it’s sustainable. That was only three or four years ago, in 2014.

Traditionally, in global health it can take 30 to 40 years for a product to go from an idea in the garage to scale. This can really accelerate the progress. There’s a saying that vision without execution is hallucination. It takes a village to execute. Jorge delivered the vision. It took us as a government agency to take the risk and invest in this device and it took the World Health Organization to be supportive of it and to get it to scale. We look for products that are potentially game changers, that can leapfrog existing technology and address the leading killers of newborns and mothers.

Sonia: Were there any other innovations that you awarded that also address these needs?

David: Yes, over the course of the eight years that we have run the Saving Lives at Birth Grand Challenge we have awarded some 120 different awards to innovators. Some awards were as low as $250,000. Some as high as two million dollars in order to be catalytic. Yes, we’ve seen a whole host of ideas. About 15% of these will transition through development and get to scale. That doesn’t sound like a lot but when you’re looking for new approaches to reach what we call the last mile in real rural settings, it’s proven to be a pretty successful model. We’re going to be seeing more of it.

Claudia Weill on directing BUMP

Sonia: Claudia, one of my favorite storylines in the play is during colonial times when you see and feel the terror of giving birth without the aid of technology or community. What was it like directing that scene?

Claudia Weill: We were very lucky. We found an amazing group of actors who really brought the play to life. The two actors in that scene, Lucy DeVito and Jenny O’Hara, were fantastic in making it come to life. When Chiara writes “1690” she writes it almost as a contemporary scene. It’s not like, ye ole. It’s very hip and edgy. That made it very easy to direct and easy to connect it with the other material.

Sonia: Can you tell us about the creation of the set and the development of the prototype for the device?

Claudia: I wasn’t so much involved in developing the prototype. We had wonderful prop people who were. In terms of the set, we worked with this wonderful woman Kristen Robinson. Early on, we realized we had to create the world of the Internet and to bring it onstage in some alternate space. She came up with this wonderful idea of this window. Everything that happens in the window is somehow connected with the Internet, whether it’s a YouTube video or a chat room or whatever. I thought that was a marvelous visual concept, a visual metaphor for what Chiara is doing in the play. One of the things Chiara is writing about is that we are more intimate with our devices and with what’s happening on the Internet than we are with the person next to us in bed. It’s as if that person in the device is in the room. It’s not a remote thing. The set brings that home.

Why outsiders may be key to medical innovation

Sonia: Jorge, how do you think your experience as a car mechanic helped you to think about the problem that your device solved?

Jorge (translated by Mario): He has several patents related to automotive mechanics. When he was having issues with mechanics in his garage, he used to go to bed with the problem and woke up with the solution. This time when he had the idea his wife was not pregnant. He thanks God for giving him this idea. He wants to congratulate the actor who portrayed him on stage. He has only one complaint. In the program he is not described as an Argentine mechanic but simply as a grandfather inventing the device.

Sonia: I have a question for any of the panelists. Forceps were invented in the seventeenth century. I’m surprised there haven’t been more innovations in this area. Do any of you have ideas as to why that is?

Mario: There have been many attempts to improve the forceps and the vacuum extractor. There are at least one thousand different kinds of forceps. Obstetricians have typically tried to improve on what’s already existing. Being a car mechanic, Jorge looked at the problem from a different perspective. Speaking as an obstetrician, I know we often refer to labor and delivery as a biological process, but mostly it’s a mechanical process. The baby has to go down the birth canal and navigate different diameters, taking different positions as it is being pushed by the mother. It has always struck me that Jorge has a better understanding of the dynamics of delivery than a physician. He always says he’s a car mechanic. He’s not a doctor, so he doesn’t have any kind of biological background. This always brings to mind for me the saying that sometimes imagination is more important than knowledge. What you need sometimes is someone who takes a totally different view who has a lot of creative imagination. It’s great that there are now platforms available for innovation. Innovation can come from totally different backgrounds. This is my view. This is why there has not been so much innovation. We had to wait for Jorge.

David: I’d add that it’s very expensive to develop new medical technologies. For a good reason. We want to make sure that they’re safe. So they often require these randomized controlled trials which are very expensive. If you’re a medical device company like Becton Dickinson, you want to make sure that the devices you’re developing and testing will allow you to make more of those and make a profit. Often In these low resource settings . . . in northern Nigeria, for example, women often will give birth by themselves by tradition. These are completely different markets with different user needs than are available in more developed places. There is not necessarily an incentive for innovation in these low resource stings. Fortunately, Becton Dickinson is very progressive in moving into these emerging markets–the fastest growing markets in the world, Africa and Southeast Asia–so we’ll likely see more of this innovation coming sooner than later.

How the testing process for a new medical device works

Question from audience: The play makes a point of the difficulty of moving from testing a device on dummies to clinical trials on people. How does that process work? How are the first human testers chosen?

Jorge (translated by Mario): There is a process you have to go through in order to get a device approved. There is an ethics committee that has to approve it. In this case, there actually was a first woman to test the device that had never been used before in the world. Jorge was involved in approaching the women. Jorge is really grateful to the first woman. We have to remember that the women in Argentina were going to have a normal delivery. They would not actually need the device. They needed to start with women who were going to deliver anyway. So the first women who agreed to participate were doing it for science. When you do research of this kind there is a very detailed form the women have to read and discuss with their family. Reading the two or three pages describing all the possible risks could have been very scary. Despite that, the women decided to participate. Another requirement of the ethics committee was that the first test had to be conducted with women who had advanced education, a university degree. They wanted a population of women who could not be interpreted as being disadvantaged or who might consent without properly understanding what they were consenting to.

What inspired BUMP

Question from the audience: Chiara, what was it about Jorge’s story that made you want to write a play about him?

Chiara: I read this article and I just loved the idea of a man, a mechanic, someone not in the medical field, someone just completely out of it in this very female experience and I thought this was a funny juxtaposition. The idea of someone with a plastic uterus in his garage just seemed lovely.

TOPICS