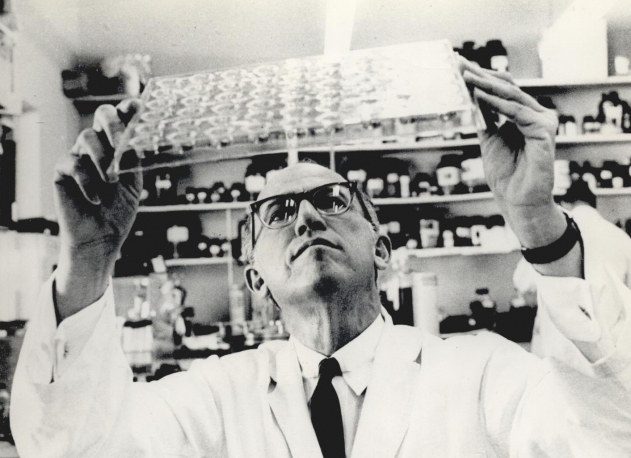

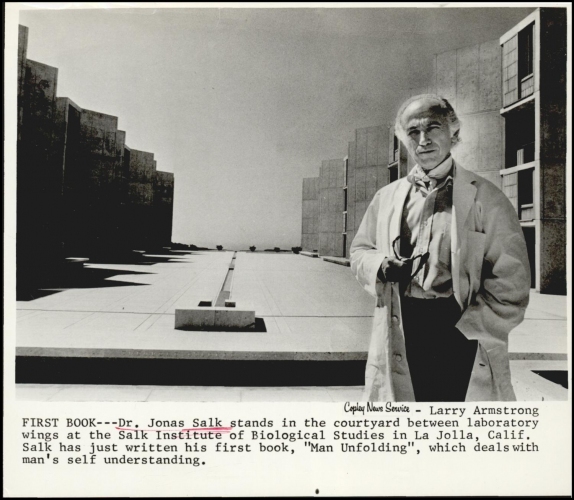

The first virus to be fully eradicated from the human population with a vaccine was smallpox. Polio is close to being next. The main figure in the development of the polio vaccine is Jonas Salk, a virologist who tested the vaccine on himself and his family, in what were the first human trials of the drug. He successfully developed one deemed safe in 1955. Writer and director Arkesh Ajay (MISSISSIPPI REQUIEM) has a new feature script about Salk called THE KITCHEN CHEMIST’S WAR. The script includes a period of Salk’s life beginning when he was being investigated by the FBI for ties to the Communist Party.

Ajay received Sloan-support for his script in 2015 through UCLA while he was getting his graduate degree in directing. The 2017 Sloan Film Summit presented a staged reading of the screenplay, one of only three projects to be presented. Science & Film spoke with Ajay by phone in November about the project.

Science & Film: How did you become interested in Jonas Salk?

Arkesh Ajay: In middle school I read about an incident that stuck with me: Jonas Salk injecting himself and his family with the vaccine because he was so sure that it would work. When I was at UCLA and saw that Sloan gives support to screenplays about science, that story came to mind.

Growing up, I was really into science and wasn’t bad at it. My dad wanted me to be an engineer. When I told him I didn’t want to be one his compromise was, maybe you can become a doctor? One of the things that I like about science is that it is very inspirational to see a person work creating something new. Turning to art, it’s very similar. You have this seed of an idea in your head and you start reading and exploring and sketching out characters. If you’re trying to make a film it’s three, four, five years of your life trying to make this one thing that might not become anything. But while you’re in it, it becomes the most important thing.

S&F: Did your experience as a writer help you understand the character of Jonas Salk?

AA: There are a couple things about Jonas Salk that resonate. He was working without a lot of faith from the scientific community. When he started polio research in 1945 he was entering a field that was replete with scientists who had already been working on it for a couple decades. He had this resolve and ambition that he could keep going that resonates with being a writer.

S&F: How did you decide which parts of Salk’s life to focus on in THE KITCHEN CHEMIST’S WAR? Are you thinking of your film as a biopic?

AA: There is no way you can discount what happens in anyone’s childhood. But the problem with that is if you’re looking at a man who is 45 years old, like Jonas Salk, and you’re trying to see why he has this blinding, obsessive ambition, then obviously the answer to a lot of that lies in how he was brought up and what he was seeing around him. I would still say THE KITCHEN CHEMIST’S WAR is a biopic because I am dealing with what I think is the most substantial part of his life. What I am looking at is a period of ten years from when he joins the polio research during the March of Dimes to when he invents the polio vaccine.

As I was working on this, my starting point was finding out what brought this guy to inject himself and his family, because that seems like a really bold move. Then I found out that there was an FBI investigation of Salk. I started to read up about that and realized that it could become the vehicle for me. From a narrative point of view, the political climate at that point was so rife with this fear of communism and soviet spies that even scientists were not spared. It was entirely fear mongering, as we know now. I think it is interesting to look at because we are back in such a political climate where there is mistrust and fear from all sides. The other thing is, structurally as a writer the investigation solves a big problem for me which was, how do I go into Jonas Salk’s back story? As I was saying, a lot of answers lie in his youth. If an FBI investigation is going on, they would have definitely looked into it. So if I use the FBI investigation as the driving force of my story it allows me to jump back and forth in years. It allowed me to tell a bilinear story. I realized the dramatic arc can be better built.

I think it’s a biography because so much happened during these ten years and there are so many forces he is fighting against. The flip side to Jonas Salk, which is what I think makes his character intriguing, is that I think he is driven by ambition, by the idea that people will recognize how good he is as much as he is driven by the idea of what impact his vaccine can have. He invents the vaccine in 1955 and the pharmaceutical companies want to patent it. There was a rough estimate that it would have been the equivalent of seven to eight billion dollars at that point. Salk refuses to patent it because as he famously says, “could you patent the sun?” He is definitely a man who is giving. But it also tells you that he’s not driven by what a lot of other people are driven by: he’s not driven by money. He knows that if you have something as big as that and you don’t patent that you become a celebrity in the public eye.

After his vaccine, he becomes a celebrity. He starts living the scientist slash rock star lifestyle. He wants to shift to cancer research right after and believes he can develop a cancer vaccine. Unfortunately he couldn’t, but he was so enthused by his success that he thought he was going to solve it. It was very intriguing to see a man fight the entire scientific community, fight the FBI which was led by J. Edgar Hoover–the mafia boss of the country. There was an active campaign by the FBI to discredit his work. At the same time his personal life was not great. All of these things in just ten years while working towards something that was going to be earth shattering. I think the story just has to be told.

S&F: Have there been other film depictions of Jonas Salk?

AA: When I first started researching, I was sure there had been films made about him. But then I realized that there haven’t been. If I’m right, movie studios in the ’70s had tried to make his life story. I think Warner Brothers had tried to do it–they had a script apparently but it was never made. There are factual scientific documentaries but no stories about his life, nothing to explore who Jonas Salk was.

S&F: You grew up in New Delhi. Is polio eradicated there?

AA: India is now considered entirely polio-free. Until very recently, you would see enormous government campaigns about polio. The campaign slogan is “two drops of life,” which means the vaccine being given is an oral vaccine–which goes through the gut–which is the Sabin vaccine [developed by Albert Sabin, a contemporary of Salk’s who developed an oral polio vaccine]. I worked a bit in the social sector after college and the moment you travel to rural areas in India you realize that it’s a very real disease that exists. Polio is a disease that is in the collective conscience of the country. Unlike in the U.S. where people of this generation look at it as something of the past.

S&F: How much do you keep up on the research?

AA: Unfortunately, in the last three to four years a lot of things that people around the world believed were things of the past have suddenly become things of the present. Even in America, people suddenly don’t want to vaccinate. The belief that it causes autism has suddenly gained traction. It’s unfortunate that we’re suddenly debating things people had debated 50 or 60 years ago.

In the last couple of years, there are some regions that have tried to shift back to Salk vaccines because apparently Sabin vaccines are more difficult to transport. So transporting it into the interiors of Asian or African continents the Sabin vaccine becomes ineffective. The thing with the Salk vaccine is that it’s an injection and people are more comfortable with drops. Anyone can give two drops, volunteers can give polio drops, but if you want injections you have to send out healthcare professionals which has a cost. There is still more to find out about the field.

S&F: Are you going to continue to work on the script now that you’ve graduated from UCLA?

AA: I will. Right after I won the Sloan award in 2015 I was working on an adaptation of a William Faulkner story with James Franco and Topher Grace. I’ve spent the past couple of years shooting in film school these short films which are now complete. I have begun the rewrite on THE KITCHEN CHEMIST’S WAR because I think the script can benefit from at least another couple of months of work. I have applied with it to the Sundance Labs now and it’s in the second round. It is one those films that cannot be made for a shoestring budget. It will hurt its prospects if I try to push it through like that; it needs a little more support. My intention is to rewrite this and then try to put it through labs, and other support structures that Sloan has, and even maybe beyond Sloan, and hopefully sometime towards the later half of next year I can start thinking about where to take it.

Arkesh Ajay received support for THE KITCHEN CHEMIST’S war through the Sloan Foundation’s partnership with UCLA, which grants screenwriting a production awards to graduate film students integrating science and technology into their work. Stay tuned to Science & Film for more as Ajay’s film develops.

FILMMAKERS

PARTNERS

TOPICS