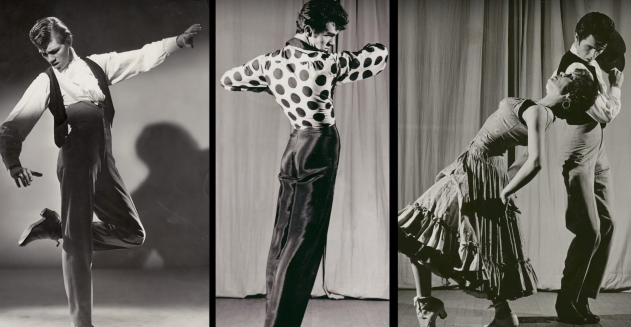

Hampton Fancher and Science & Film sat down an afternoon in late August to talk about BLADE RUNNER. Clearly a lover of music, with an alto saxophone mounted in a corner and classical playing on speaker, Fancher and Science & Film spoke in his apartment filled with nonfiction books, with a spinning mobile of an Eadward Muybridge horse galloping next to a photograph of a Sonia Delaunay painting. Fancher began his stage career as a flamenco dancer in Los Angeles. He went on to write one of the most influential science fiction films ever; BLADE RUNNER was released in 1982 starring Harrison Ford–who had been in STAR WARS five years earlier–and Sean Young.

Fancher adapted BLADE RUNNER from Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which was the first of Dick’s 44 novels to be adapted for the screen (others include MINORITY REPORT and TOTAL RECALL). A sequel, BLADE RUNNER 2049, was written by Fancher and will be released on October 6, 2017. It is directed by Denis Villeneuve (ARRIVAL), and again stars Harrison Ford.

Science & Film: The first BLADE RUNNER was released 1982. Thirty-five years later you’ve written a film that again takes place in the future. Has your vision of the future changed?

Hampton Fancher: When I first started to write BLADE RUNNER 2049 I was stymied because I’m not a technical person. I’m not a science fiction person, that’s not where I go in my reading. But I had a simple idea: anything can happen on the streets of that world. Whatever the little insanities we run into in New York City, this could be more so. I think I made it crazy. I didn’t make it crazy on purpose, but that’s what kept happening in the writing. That idea of anything can happen, like a nightmare only in the brick and mortar of the future. Denis [Villeneuve] wanted to stay grounded in terms of the film technology and not do any miniatures. I think that’s one of the reasons they filmed in Budapest because there they could afford to make a world and a soundstage.

S&F: Discerning difference between replicants and humans is central to BLADE RUNNER. You said you’re not a science fiction person, but why are you interested in replicants and artificial intelligence?

HF: I am interested in what it is to be human as in humane, and how so much of our history is the opposite. The solution to that, to some degree, is empathy. We’re lost because of our inability to live within our empathetic impulses, but the contradictions are intriguing. That’s in BLADE RUNNER. Plus the idea of perfecting ourselves, but then Roy Batty puts his maker’s eyes out.

S&F: How did you learn about Philip K. Dick’s work?

HF: I called a friend of mine because I wanted to try to make a film that was different from the kind of films that I had been trying to direct. Those projects were impossible. So I thought, fuck that, I’m just going to do something that hopefully could be done, I mean, as in commercial. I thought I would option a couple of things and make it work. But I was stupid, way off the mark, that was 1975 and my choices were naïve for the time. Charles Bukowski, William Burroughs, and Philip K. Dick were not exactly Hollywood attractions back then. I came by Dick because I had the feeling that the next big thing was going to be science fiction.

S&F: Why did you think that?

HF: It was in the air. So I asked my friend if he knew any science fiction. He said, what about Ray Bradbury? I said no man, I’ve read Ray Bradbury and that’s not the kind of science fiction I’m talking about. So he suggested Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? I thought that was a funny and catchy title. I went out, got it, read it, and I didn’t like it that much but I saw the through-line: detective, bureaucrat, chasing after androids. Then, I couldn’t find Dick to get the rights. After two or three years his agent told me to forget it, that he didn’t even know where he was. So I forgot it, but I’m walking down the street in Beverly Hills one day and run into Ray Bradbury and ask him if he knows of a guy named Philip K. Dick. He gave me a phone number in Pomona. I called Dick and he said come on out. But the rights to the book weren’t free. Three years later, I recommended to my buddy Brian [Kelly] that he try it. By then the rights were free and Brian optioned it.

When Brian got the rights, I started writing BLADE RUNNER. I wrote quite a bit, two or three drafts, before Ridley [Scott] came. At first we had another director and another deal–we were going to do it with Universal and Robert Mulligan from TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD was going to direct. It was a very little movie set in just a few rooms for a budget of nine million dollars. Then that fell apart. At that point, the producer Michael Deeley suggested Ridley Scott. At the time, I told him I didn’t want Ridley because back then I wasn’t seeing him as an actor’s director. I loved ALIEN, which came out the year before. Ridley was so hot that if he would do it, Deeley said, we would be financed in a minute. He said, do you want to make this movie or not? And I said okay. Ridley came to Los Angeles to talk with us. There was a breakfast meeting between he and Michael at the Beverly Hills Hotel; people knew about the project, and saw Ridley and Michael, and we had four offers by the end of the day.

S&F: How is it working with Denis Villeneuve on BLADE RUNNER 2049?

HF: Denis is everything; he’s strong and he’s soft, tender, smart and perceptive, inventive, knows a lot and listens a lot. There is nobody like him. And he’s actually sweet, you would never know that he was the guy who could direct SICARIO. There is so much muscle in that film, like Ridley’s BLACK HAWK DOWN. Denis is warm and transparent–he’ll tell you what he’s thinking and how he feels.

S&F: I thought there was a bit of humor or satire in the first BLADE RUNNER. Does that come through in this new one?

HF: Ridley is extremely droll, very funny man. By the way I disagree with you [that there is humor in the film]. I find not a speck of humor in BLADE RUNNER. I don’t see much humor in BLADE RUNNER but Harrison [Ford] is a funny man. I never knew him but I met him recently at Comic Con. He comes up to me and says–long time. I said, I don’t think it’s been a long time. He said, well how long has it been? I said, it’s been never. I’ve never met you. He said, yes you did. I said, no, but I wrote you a fan letter. He said, you did? I never got it. I said, I never sent it. He said, that figures. In other words, he’d already taken my measure.

S&F: How much did you write the visual style of the city into the script for BLADE RUNNER 2049 and BLADE RUNNER?

HF: You can’t just write dialogue, and it’s not a novel so you can’t write internalized thoughts, so everything you’re writing is either description or dialogue. It is a very interesting kind of writing. The demands of screenwriting are very similar to the demands of poetry; it is about compression. You have to give a feeling to the reader and If you do it, it’s got to be simple and black-and-white in a sense, yet it’s got to have a little muscle to it. It’s got to be fun to read. I learned how to do that. At first I did too much; I was writing screenplays like Joseph Conrad would write screenplays. I’d write 200-page screenplays. Then, somebody turned me onto Elmore Leonard [novelist and screenwriter of such films as JACKIE BROWN]. That’s what got me sharp in terms of not getting superfluous. I just wrote a book called The Wall Will Tell You and it’s about how to write a screenplay.

S&F: Do you ever draw while you’re writing?

HF: Always. Drawing is key for me. I’m not a great drawer; I am a graphic artist, I do that all the time, and I can paint a bit, but the drawing… I taught at NYU film school and I told my students that if you are stuck, go pick up a pencil and doodle. It will cut you loose. People have thanked me for that piece of advice. Ridley draws a lot, but he’s an artist. Literally, he went to art school and he could draw this room in five minutes.

S&F: When will you see the new film? Are you looking forward to seeing it?

HF: I’m scared. I never asked to see it. I’ve been involved in it for a very long time. By the way, Alcon Entertainment has been great. Everybody has been. Like Denis, everyone has been warm and welcoming and encouraging. It is rare in Hollywood. This film has a feeling of camaraderie and good faith. They wanted me to go to Budapest but I couldn’t go. So now, I don’t know any more about the film than you know.

S&F: Except that you wrote it.

HF: I wrote a treatment and first draft. Then Michael Green, who is wonderful and smart, wrote the shooting draft, the final script.

S&F: You have been associated with BLADE RUNNER for 35 years now of your career. Do you worry about that association overshadowing your other work?

HF: I am lucky in more than a professional and vocational sense–BLADE RUNNER has been and continues to be a great good fortune. It’s a big fairytale of a wagon and I’m sitting in the golden hay of it.

Before writing BLADE RUNNER, Hampton Fancher had a twenty-year career as an actor in numerous Westerns such as the series GUNSMOKE and in romantic dramas such as THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN. He directed THE MINUS MAN (1999), starring Owen Wilson, which Fancher also wrote. Michael Almereyda’s wonderful new documentary ESCAPES showcases Fancher through film clips and a series of interviews. The Museum of the Moving Image will screen ESCAPES to coincide with BLADE RUNNER 2049’s theatrical release.

BLADE RUNNER 2049 stars Ryan Gosling, Robin Wright, and Harrison Ford. Ridley Scott is one of the executive producers. It is directed by Denis Villeneuve. The film will be released into theatres on October 6, 2017.

TOPICS