Films from the silent film era were rarely silent. Before the Jazz Singer sang from the screen in 1927, as early as 1913 films were shown with recorded sound. Movie mogul and inventor Thomas Edison introduced the Kinetophone in the late 1880s; just as his motion picture camera the Kinteograph could record movement, so the Kinetophone could record sound. The sound was recorded on a cylinder which viewers could then listen to while watching a film on Edison’s patented Kinetoscope viewer. But this was a closed viewing system–more similar to a Virtual Reality “theatre” of today where viewers have individual experiences in a shared space. This isolated experience became outdated with the preponderance of movie theaters, but even then this separation of sound from projected image was a challenging system for projectionists to operate. Record needles would often skip grooves on cylinder so that the sound and image stopped syncing. Researchers began experimenting with recording sound directly onto film.

Sound on film was “a system where you recorded the sound like recording on a magnetic tape,” George Willeman, nitrate vault manager at the Library of Congress told Science & Film on the phone. “But instead of the tape you had a machine loaded with sensitive motion picture film.” On such filmstrips it is possible to literally see the sound.

Sound was recorded onto the filmstrip via light. A light valve was a small device that stayed closed so long as there was no sound. Then, “as soon as sound is introduced, the [microphone] amplifier turns the sound into electric pulses and makes the light valve open and close very quickly. The more sound, the wider the valve opens. The light comes through the valve and it imprints an image of the sound on the edge of that filmstrip,” Willeman explained. This sound-on-film format is called variable-density. In the Museum of the Moving Image's collection is a “Variable-Density Optical Sound Recorder” from 1929 that recorded on 35mm filmstrips; it was used by Paramount Pictures in the Kaufman Astoria Studios.

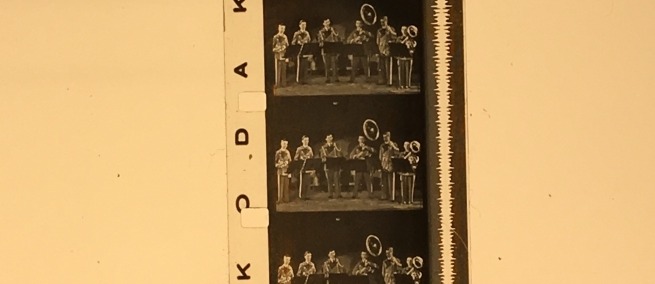

Since the soundtrack was taking up physical space on the filmstrip, Kodak Research Laboratories suggested in 1927 that 16mm sound film stock have “only one row of sprocket holes, on the left, creating room for the optical soundtrack to the right of the picture,” the Museum of the Moving Image's core exhibition “Behind the Screen” tells. The exhibition illustrates that because of this alteration, the size of the frame did not need to be significantly reduced to make room for the soundtrack. By 1935, this format for displaying recorded sound was standard.

A projector not only illuminated the film image onto the screen, it translated the visual information about the sound for the audience to hear. A projector had to have “a second little lens and a light source that goes through the sound and focuses those little squiggles on a light-sensitive chip,” George Willeman said. “That chip takes that light and turns it back into sound waves through the [microphone’s] amplifier, which then plays it out the speaker.”

The Museum of the Moving Image has a few examples of filmstrips with optical recording on display. From 1948, THE ORIGINAL AMATEUR HOUR shows sound waves, with heights dependent on amplitude, to the right of the image on 16mm film. On 35mm film, which was wide enough to retain perforations on both sides, sound was recorded on the left–as seen in a filmstrip from MYSTIC PIZZA from 1988.

The Museum of the Moving Image is located in Astoria, New York. Its exhibition “Behind the Screen” is open to the public Tuesday through Sunday.