Hedy Lamarr, so beautiful that conversation reportedly stopped when she entered a room, was not only a Hollywood actress but also a genius inventor. Susan Sarandon’s production company, Reframed Pictures, is bringing her story to screen in a documentary–BOMBSHELL: THE HEDY LAMARR STORY–premiering at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival. Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in 1914 Vienna to Jewish parents. She was then renamed Hedy Lamarr on her way to Hollywood. Best known for her role in ECSTASY and SAMSON AND DELILAH, Lamarr escaped an early marriage to a fascist arms dealer and fled to Hollywood. Along with composer George Antheil, one of the pioneers of electronic music, she invented a technology known as frequency hopping, which forms the basis for modern day GPS and cell phone technology.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes wrote the definitive biography, Hedy’s Folly, of Hedy Lamarr. The film BOMBSHELL was adapted from Rhodes’s book by Alexdandra Dean, who also directed. The documentary features luminaries such as Mel Brooks, Peter Bogdanovich, and Diane Kruger. Kruger is set to play Hedy Lamarr in a four-part miniseries currently in production. The book, documentary, and miniseries are supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Science & Film spoke on the phone with Rhodes from his home in California.

Science & Film: How did you become interested in Hedy Lamarr? Why do you think her story is such a rich subject to explore?

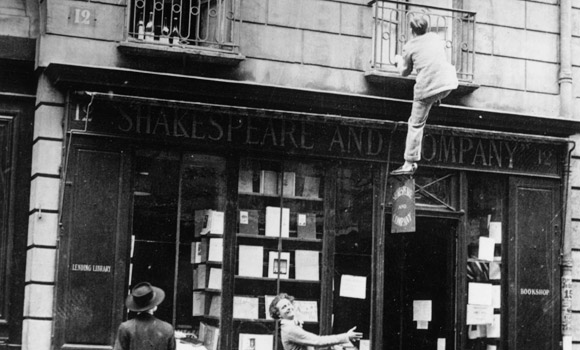

Richard Rhodes: I was on a Sloan Foundation committee that was involved in selecting book subjects to support. We were making a list of 20th century American inventors and someone suggested Hedy Lamarr, and like most people I said, “really?” Once I’d heard a bit more about it, I said, “I’ll take that one.” I did my senior thesis at Yale on James Joyce, among others, so I had some background in that particular era of the 1920s and '30s in Europe and was intrigued. George Antheil, Hedy’s partner in crime lived in Paris during the earlier 1920s. There’s a famous photograph of George climbing up to the second floor of Shakespeare and Company on the outside wall because he’d forgotten his key. George and his wife lived on the balcony of the bookstore and used it as a library, and of course the owner published the first edition of Joyce’s Ulysses. Then I also had an longstanding interest in technology. So all of that came together for me.

The more I learned about Hedy and George in their separate trajectories toward meeting up in Hollywood, the more fun, the more interesting, and the richer the story seemed. George was just an extraordinary man in his own right. Hedy came up with the idea of protecting the radio signal of a radio-controlled torpedo by making it jump rapidly and randomly from frequency to frequency so that it couldn’t be tracked and therefore couldn’t be jammed. The problem was there weren’t any electronic means at hand to operate the frequency-hopping system. George realized that you could use miniaturized player-piano mechanisms, synced between the guiding aircraft and the torpedo, to control a torpedo. The Navy didn’t get the point and didn’t use the system, but later, when the miniaturized electronics came along, it was applied to all military communications, then GPS, then car telephones and finally Bluetooth and some cell-phone systems.

S&F: How did you go about researching the technology?

RR: I start reading the available literature and checking the bibliographies and the footnotes. Most of the good stuff is always in the footnotes and the bibliographies. Beinecke Library at Yale had a large collection of correspondence between George and U.S. Ambassador William Bullitt. Bullitt had a salon in Paris during the 20s, when he was ambassador to France, which George frequented—that’s how they knew each other. Among the many letters that George wrote to Bullitt over the years was a fairly good collection of detailed descriptions of his work with Hedy, her invention and how they went about developing it. There was very little documentation on Hedy’s side. The Bullitt-Antheil correspondence plus one article that appeared in Modern Romances Magazine in 1938, was just about it. Fortunately, it was enough. The Modern Romances article was a godsend. It was written by a woman who had the wonderful idea of casting it all in Hedy’s voice, so it was as if Hedy herself were describing her experiences: her early movies, her first marriage to Friedrich Mandl, the Austrian arms baron; her father’s sudden death and how that trauma triggered her transformation into the independent, really protofeminist person she became. The article did discuss how Hedy got to Hollywood, which is an interesting story in itself: of all the European émigrés who escaped Nazi Germany and Nazi Austria, she was one of the very few who succeeded in moving to another culture and becoming a full-fledged star herself. There were so very few who could make the transition linguistically or culturally. She really was a resourceful human being–I think because of her father’s strong influence on her as a child.

S&F: What did her father do?

RR: Her father was a bank director in Vienna, a handsome athlete with a strong interest in technology. When he and Hedy, his only child, went for walks through Vienna, he would explain to her how things worked—the streetcar, the power plant. I suspect that’s where her interest in technology originated. But then, of course, her first marriage to Fritz Mandl, an arms merchant but also a consulting engineer, found her often at the dinner table of one of their mansions or hunting lodges supposedly merely an arm piece, but in fact a highly intelligent woman, bored with chitchat, listening to all these German and Italian admirals and generals discussing their problems with their new planes, tanks and torpedoes. She was educated as a debutante, but she got a second education, as it were, sitting at the dinner table looking pretty. Her great statement about that: “I can tell you how to be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” She used her beauty, certainly, to achieve fame and fortune, but she deeply resented how few people ever saw beyond her looks to her intelligence. She said once, “My face is my curse.”

S&F: She then worked so hard to preserve her face as she got older, undergoing many plastic surgeries.

RR: Yes, that’s right. And of course she understood that her face wasn’t her curse, it was her meal ticket, but it frustrated her that she was not taken seriously as an actress. She was taken seriously in Europe, but not in Hollywood. She was assigned one ridiculous role after another. In WHITE CARGO (1942), for example, with brown face makeup, where she plays the role of a seductive native girl: “I am Tondelayo.” She did finally receive recognition for her invention of frequency-hopping, late in life. Her private response was characteristic. “It’s about time!”

S&F: You advised on the documentary BOMBSHELL: THE HEDY LAMARR STORY. What do you see as the challenges of bringing Hedy’s story to screen?

RR: The documentary is going to tell the full story because they can, because it’s a documentary. I’m sure there is always a temptation to deal with the Hollywood side of her story, and her growing old, and all those things that she struggled with, and minimize her technical side. She was arrested for shoplifting later on and famously told the officer who arrested her, “they don’t mind, I always write them a check afterwards." It was a sport for her, evidently; she was bored. I assume the documentary will include her inventions—after all, that’s what makes her story unusual. Frequency-hopping was probably her most important invention. Howard Hughes loaned her a couple of chemists in her stardom days when she was working on a tablet that you could drop into a glass of water that would fizz up and make a flavored soda—early Alka-Seltzer, as it were. We would be more familiar with her inventions if she had pursued their development—that’s the hard part of being an inventor—but for her inventing was just a hobby, something to do for an Hollywood star who didn’t drink and didn’t like loud parties.

S&F: What else did she invent?

RR: She invented a chair to attach on a pivot in a shower so that people who couldn’t stand could shower and then just swivel out to dry off. She worked on an improved stoplight. She invented a little box that attached to a box of tissue to give you a place to put your tissue after you blew your nose. Inventors are a very different group from scientists or engineers. They aren’t necessarily technically skilled. Hedy certainly wasn’t. In an interview she gave to the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes in 1945 about her invention of frequency hopping she said airily, “I let George handle the chemistry.”

She said something once about her work on military technology that is often quoted by people who simply don’t believe she could have invented something so fundamental as frequency-hopping. She said that early in the war she was thinking about going to Washington to work with the Council of Inventors. They could ask her questions, she said, and she would answer them. Some historians think that was the height of grandiosity, but in fact, what she clearly was talking about was being debriefed of all of the dinner conversations with the German and Austrian technical experts. She had a lot of fortuitous espionage, as it were, to download for the use of the U. S. government, and she was immensely grateful to have been welcomed into America and allowed to become a citizen.

S&F: Do you think she wanted to be credited as an inventor, more so than as an actress?

RR: Both, I think. She was really unhappy that she did not get credit for inventing frequency hopping until the end of her life. She was well-aware of what her invention had become and often complained so that when, for example, she heard they were finally going to recognize her, her son asked her what she was going to say and she said, I’m going to say “Well, it’s about time.” She didn’t want any money for it—she and George gave it to the Navy for free--but like most people who make discoveries and inventions she at least wanted credit. And that did finally come to her.

There was a whole generation of early digital wireless developers, some of whom I interviewed, who were teenage boys when Hedy Lamarr was at the height of stardom, and they had all had crushes on her. Hedy had used her married name at the time, Markey, on the patent, which was one reason no one had realized she was the inventor. When the developers traced back the patents and figured out that “Markey” was actually Hedy Lamarr they set to work organizing an award for her—maybe just so they could meet her! She was extraordinarily beautiful. The people I talked to said that when she walked into a room, she would literally stop conversations. Later in life she became a kind of Auntie Mame figure. And she appreciated finally being recognized for her invention of frequency hopping, in 1997, by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, when she was eighty-two. I spoke with her children about what childhood home might be an appropriate venue. They both said they moved around so much, the one place they called home is the Beverly Hills Hotel. A plaque might go up there. It would certainly be appropriate.

BOMBSHELL: THE HEDY LAMARR STORY makes its world premiere on April 23 at the Tribeca Film Festival, followed by a Sloan-supported panel on Lamarr’s inventions with scientists along with writer and director Alexandra Dean, and producer Susan Sarandon.

Rhodes is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of over 25 books. Hedy’s Folly is available where books are sold. Three of his books have received support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation: Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World; The Making of the Atomic Bomb; and Hell and Good Company: The Spanish Civil War and the World It Made.

PARTNERS

TOPICS