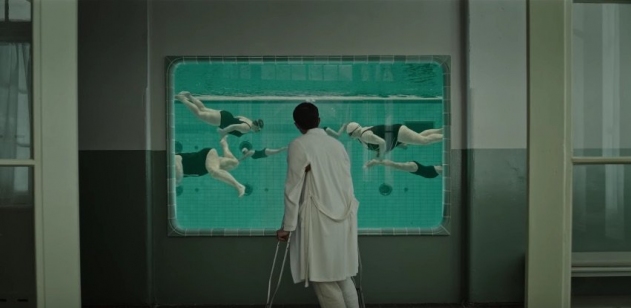

White tiles, plush bathrobes, a manicured lawn, and minute water creatures greet the star (played by Dane DeHaan) of Gore Verbinski’s thriller A CURE FOR WELLNESS when he enters a sanitarium in the Swiss Alps. There, hydrotherapy is used on patients who seem well enough but cannot seem to leave. They are encouraged to drink the water, to steam for hours, and to perform water exercises.

Sanitariums were commonly used for patients with tuberculosis before antibiotics were invented in 1946 to treat the disease. In Gore Verbinski’s film, the sanitarium is more of a metaphor. Science & Film spoke by phone with Verbinski (THE RING, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN) about A CURE FOR WELLNESS.

Science & Film: Why did you choose to set A CURE FOR WELLNESS in a sanitarium?

Gore Verbinski: Justin Haythe [the screenwriter] and I are both fans of The Magic Mountain novel. But we were more interested in taking the concept of this old place in the Alps as a setting for the modern human condition. I think that we live in an increasingly irrational world and there is a sense of denial. In the film, the sanitarium is tranquil, calm, and seems benign. As a setting it was ripe for the genre and I turned it on its head.

S&F: In the film, who is vulnerable to the diagnosis of illness?

GV: Those vulnerable to the diagnosis are the ones who are oligarchs, or from the hedge fund industry, or, in the case of DeHaan’s character, a stockbroker who wants to get ahead. This place offers a form of absolution, a sense of being not responsible because you are not well. People clutch onto that. The place is wonderful and so they want to stay; they want to leave the modern world. Cell phones don’t work, and our protagonist’s watch stops.

S&F: What research did you do for the film?

GV: I visited quite a few sanitariums all over Europe. You definitely don’t want to know how the sausage is made. Even though the places are quite nice and have scrubbed down tiles and clear water, behind those walls there was a lot of mold, mildew, and strange things in drains.

S&F: Was that surprising to you?

GV: Because we were scouting, I would go backstage and they would show me where the workers go, and not where the clients go. It is like the kitchen at a fine restaurant.

S&F: What do you think the sanitarium has to offer to the characters in your film?

GV: I think that there is something about this promise of purity. The protagonist steps away from both worlds; there is the world he comes from and then the ancient world of this place. He may not articulate it, but he is questioning the algorithm [by which people live their lives]. I think there is anxiety in that. When this genre works, it taps into some contemporary fear. The film ends and you don’t just go oh, that was a headless horseman, a gothic tale that you can put into a box and file away. When it really works, it taps into some contemporary zeitgeist. I think that there is a sense [in the population and in the film] that something is wrong with us, for us to be vulnerable to the diagnosis of this place. Our protagonist refuses to rejoin the increasingly irrational world.

A CURE FOR WELLNESS, directed by Gore Verbinski, stars Dane DeHaan, Mia Goth, and Jason Isaacs; the screenplay is written by Justin Haythe. The film is now in wide release with Twentieth Century Fox. For more, read Reverse Shot’s review of the film.