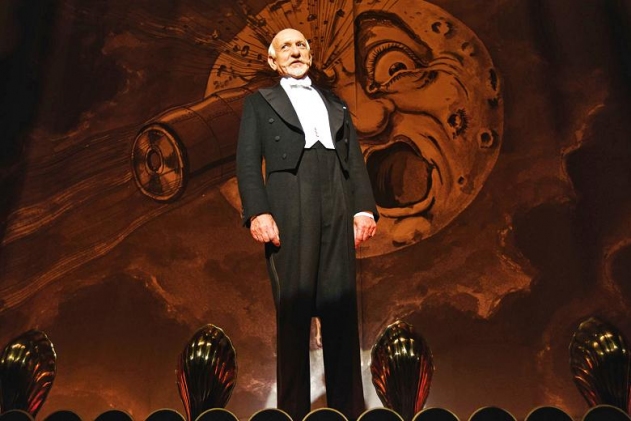

An orphan, whose only friend is an automaton, discovers the silent films of Georges Méliès and the director himself. This is the narrative of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by award-winning author and illustratorBrian Selznick. The novel was adapted into the film HUGO by Martin Scorsese. Selznick’s next book, Wonderstruck, which parallels the stories of a boy in the 1970s and a girl in the 1920s, is being adapted into a film by Todd Haynes. The film will star Michelle Williams, Julianne Moore, and Tom Noonan.

Both of Selznick’s books integrate scientific and technological themes: the mechanics of automatons, the effects of lightning strikes, Deaf culture, and the evolution of cinema technologies. HUGO is being shown in 3-D at the Museum of the Moving Image concurrent with its exhibition about Martin Scorsese. WONDERSTRUCK is set to premiere in 2017. Selznick, based in San Diego and Brooklyn, spoke with Science & Film from his home in Park Slope about adapting his books with such outstanding film directors. He has an automaton from HUGO in his apartment, one of the 15 that was used on set.

Science & Film: How did you get interested in science?

Brian Selznick: I have never thought of myself as being interested in science, but a lot of the things that I am interested in are related to science. The stories I want to tell come from things that interested me when I was a kid–movies, magic, museums, ghosts, and things like that. Hugo really started because I had seen A TRIP TO THE MOON [a silent film by Georges Méliès] years ago and thought a book about a kid who meets Méliès would be interesting, because my first book was about a boy who meets the magician Harry Houdini. But I never knew what the story would be until I was reading a book called Edison’s Eve, which is about the history of automatons. [An automaton is a humanoid robot which runs on a code to perform programmed actions.] I was intrigued by robots. I was also interested in science fiction movies when I was a kid and still enjoy watching them. It was in a book review of Edison’s Eve that I learned that Georges Méliès had a collection of automatons himself. He donated them to a museum at the end of his life and they were eventually destroyed and thrown away. I imagined a kid climbing through the garbage and finding one of those broken machines. That image intrigued me. So, in order to write about it I then needed to learn about automatons, because other than knowing what they were I didn’t know anything about them. That led me into this whole world of early machines, clockwork, and religion, because a lot of the early automatons were the center of conversations about what life is. If a machine can replicate what living creatures can do, then is the machine alive, and where does the soul reside?

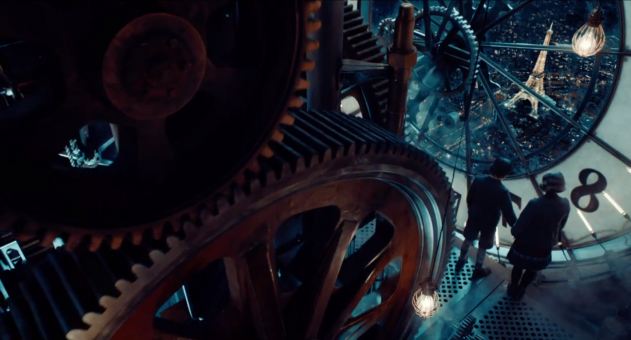

We are so disconnected from the machines we use now because we get these sleek pieces of glass which are magic, you can’t replace the battery, you don’t know how any of it works, and if it breaks you usually have to replace it. But during the technological revolution at the end of the nineteenth century, if a machine broke, and you had the wherewithal, you probably could figure out how to fix it. All of the parts were probably handmade in the first place and you could see cause and effect. The hand of the inventor was visible throughout the entire machine, lending the machine a kind of humanity that I think is really beautiful, which is now mostly lost.

S&F: It seems like you have to do a lot of research for the subjects you write about. How do you go about that?

BS: I love asking people to offer up their expertise, especially people who are experts in a niche field. I find that they often are not asked for what they know. Everyone has been very generous and eager to help–whether its giving a tour of the museum and talking to me about the objects, or the ideas related to what I’m writing about. My husband is a historian and writes about the history of science, and so he is an incredible resource as well. When I was working on Wonderstruck, I needed to write about the history of sound in the cinema and he connected me with a friend of his who is a specialist on the history of sound in silent cinema who was a huge help in making sure that aspect of the book was accurate.

S&F: How do you integrate the technical language that can come from experts with your story?

BS: Ultimately, because all of these aspects of science are in the book to support a plot point, I feel like that keeps a reign on what is there so that it is comprehensible. My books are written for kids but I try very hard to include whatever information is necessary whether or not it is information kids would be learning anyway, or whether it is something you wouldn’t learn until graduate school. I know that if the information is there for the plot the reader will be able to figure out what I’m talking about. In Wonderstruck, there is a lot about the history of museums that, if you learn at all, you learn in grad school. In the book, there is essentially the beginning of a dissertation about cabinets of wonder for ten-year-olds.

S&F: Hugo and Wonderstruck are set in the real world–at the Queens Museum, American Museum of Natural History, and the train station in Paris. That can have a big impact on cultural tourism. When The Goldfinch was published so many people went to see the painting at The Frick Collection. Was that part of your intention in setting these books where you did?

BS: Because you read a book like The Goldfinch, you feel ownership over everything in the book; you feel ownership over the museum and the painting. So, it’s like making a pilgrimage. When I was writing the The Invention of Hugo Cabret, I wanted it to feel like a fantasy, even though it’s not. There may be some pretty big coincidences, but everything that happens in Hugo could actually happen to somebody. I know that a lot of people who go to Paris stop by all the places that I mention in Hugo–they visit the train station and the clocks. The two main clocks are from the Musée D’Orsay. The Gare du Nord was the basis for a lot of the visuals itself. There is an automaton museum in Paris.

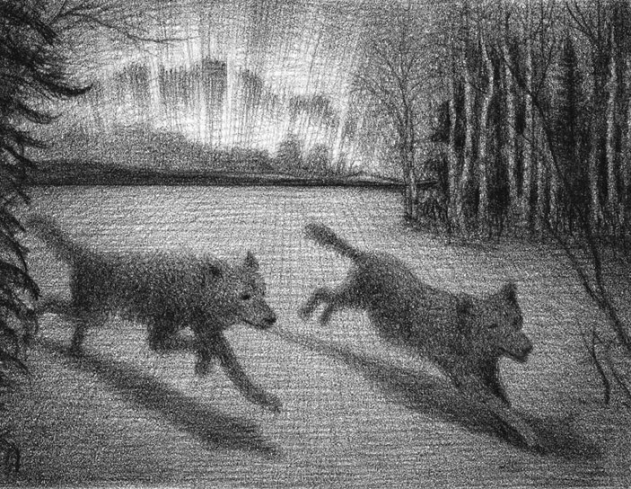

For Wonderstruck, there is the wolf diorama at the American Museum of Natural History and the panorama at the Queens Museum. The Marvels, which takes place in London, is based on a real museum which is an entire house that’s kept as if it’s the 18th and 19th century called the Dennis Severs’ House. I am a friend of the curator and he says that all the time people come to the house because they’ve read The Marvels. When you’re reading, you are very much inside your head. Being able to go visit the places mentioned in a book helps continue the pleasure of the book itself. When you’ve read The Goldfinch and you go to the museum, you’re not just visiting a museum, you’re inside the story that you loved when you were reading. It is like the book changes the way you see the world that you are in and then the world that you are in becomes the world inside the book.

S&F: What has the process of adapting Hugo and Wonderstruck been like?

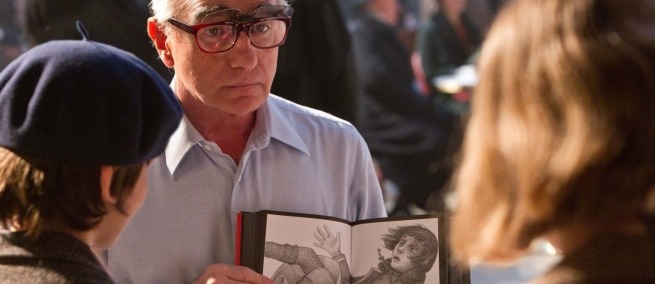

BS: I feel very lucky with the directors who have adapted my stories. The books of Hugo and Wonderstruck were designed to only have ever existed as books. I think it is fair to say I did not think about Martin Scorsese when I was writing Hugo. But, as soon as his name was brought up it felt like there was no one else who could have directed it, and Scorsese turned out to have some kind of connection to almost every character in the book: he was a lonely, sick kid who was isolated a lot like Hugo; he is a great film director; he is an archivist like Tabard; he has rediscovered lost film directors like Michael Powell the way Hugo rediscovers Méliès. One of the reviews said it was Martin Scorsese’s “imaginary autobiography.” Even the opening shot where Hugo is looking through the clock echoes the opening shot of GOODFELLAS where the kid is looking from his kitchen window to the street, relating to Scorsese himself when he was young. I also think that for Scorsese using 3-D, the most advanced cinematic technology of the moment, mimics what Méliès was doing when he was experimenting and making films.

S&F: How did Scorsese use your book, and what was it like to see it on screen?

BS: My book is told in both words and pictures, so the narrative is constantly being handed back and forth between text and images I’ve drawn. Scorsese used my drawing sequences as storyboards. I knew the script was really close to my narrative, but it wasn’t until I saw the first cut that I understood that he was recreating the picture sequence.

I became friends with Sandy Powell–the costume designer–and I joke with her that she is the only collaborator on the film who ignored everything from my book. The costumes are nothing like my costumes, but every choice she made was brilliant for the film. For instance, in the book, Hugo wears an oversized tuxedo jacket so that when he is running you can see the tail moving to indicate movement. But she is working in a medium that actually moves, so she put Hugo in the exact opposite: a jacket and pants that are too small so you have the sense he has grown out of them, which makes him more vulnerable on screen.

The movie came out in 2011, it was in production for two years before that, and it still feels like a dream.

S&F: It is a gorgeous film.

BS: It is really good! It ends with a visual essay on the history of film by Martin Scorsese. That was built into my book, but to have a version crafted by Martin Scorsese is so extraordinary and is there for people to watch for the rest of time. HUGO is so different from any other movie he has made, but in so many ways it is a key to all of his films and to who he is as a person. It was his joy and his energy that makes it such a thrilling film. I always say I feel like a proud dad; Hugo was my kid and it went off and grew up and did well and married into a nice family. It’s a great feeling.

S&F: How did Wonderstruck the movie come about?

BS: It was really from the people who I met on HUGO that WONDERSTRUCK evolved. I developed some really fantastic friendships–with John Logan and Sandy Powell. Wonderstruck tells two stories, one in pictures and one in words, and there is no cinematic way to translate that because cinema is all visuals, so again I thought I had a book that could not be adapted, which is fine because it was meant to be a book. But Sandy Powell read it and she thought Todd Haynes should direct.

S&F: Why did she say Todd Haynes?

BS: She designed costumes for VELVET GOLDMINE, CAROL, and FAR FROM HEAVEN, and I think there were themes relating to the relationship between the two boys in the story and the way it takes place in different time periods that made her think of Todd. Todd has made many movies where he intercuts different stories from different time periods, film styles, and genres going back to POISON inwhich there are three interlocking stories that weave together to make a larger point about the AIDS crisis and the larger community. It was Sandy’s idea to give the screenplay for CAROL to Todd so she knows what he likes–they are very close.

S&F: John Logan adapted Hugo, but you have adapted Wonderstruck yourself. What was it like writing a screenplay?

BS: John Logan had approached me about adapting Wonderstruck, and then got busy, so finally I wrote the screenplay with his guidance. He was very generous and read everything I wrote and gave me notes. It took me about nine months. Todd was editing CAROL at the time, and because he is a very monogamous worker, he couldn’t read another screenplay. When he finally had the chance to read it he wrote me a long email about how much he loved the story, and soon he’d decided it would be his next film. I then began doing rewrites with Todd. As a fan of Todd’s films since POISON came out, it was so extraordinary to be able to sit in a café with him and talk about the movie.

Todd brings this encyclopedic knowledge of the history of film, so we started sharing movies with each other from the ‘70s that we loved. Todd told me about Nicolas Roeg’s film WALKABOUT, which I loved, and we discussed a favorite movie of mine from the time period, THE CONVERSATION. He also wanted to look at movies with very strong child performances so he recommended HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY with Roddy McDowall who gives one of the most beautiful child performances I have seen.

S&F: Where was WONDERSTRUCK shot?

BS: It was all shot in New York State: upstate, in Manhattan, at the Museum of Natural History, and at the Queens Museum. The story opens in Minnesota so we went to upstate New York which is a good proxy setting. Hoboken is also portrayed by a place upstate. They found wonderful locations–Mark Friedberg, the set designer, is a genius.

Todd described New York in the 1920s as a time when everything was being built up higher and higher, and in the 1970s everything was falling down. As soon as something is articulated clearly it clarifies how things are designed and written; it gives you a framework that is really helpful for all the collaborators. He could say that same sentence to the set designer, costume designer, and lighting designer and it helped all of them. It was a really extraordinary team. I was on set almost every day for the entire filming.

S&F: How long did it take to shoot the film?

BS: I think it was about two months. They rebuilt Times Square from 1977 in Brooklyn with 200 extras. The scene was supposed to take place during the heat wave of 1977, so they’re all wearing skimpy costumes but we filmed on a cold day, so they had silver marathon blankets between takes and then when it was action they were covered in fake sweat, like a gel, and they would pull on the collar of their shirts and wave their hands in front of their face. It was a lot of heat acting that was very impressive. Watching the mechanics of how all of that happens, every day, for two months, was something to see.

S&F: Have you watched the finished film?

BS: I have seen some of the first cuts. It is beautiful. It is a really interesting children’s movie. Half of the movie is silent, and is set in 1927, and then the parts from 1977 are shot like a movie from 1977. So, you have a movie that is half black and white and silent, and half color and sound filled with ‘70s effects. With WONDERSTRUCK, we use silence and the ideas related to silent cinema–you think at first it is evoking silent movies, but you find out that it is silent because the main character is deaf, so the silence is not responding to the technology, it is reflecting the experience of the main character.

One of the things that intrigues me about books is that even language is a visual thing. You are looking at black symbols on a white page, but when you remember a book you don’t generally remember words on a page, you remember a character and what they look like doing the thing they did in the book. When you love a book, and you see the movie adaptation sometimes it is jarring because the character doesn’t look the way you imagined them. But with my books, the reader has drawings so you get to see the characters, but the words and pictures are never working simultaneously in my books. In Hugo, the words stop when the pictures begin and the pictures continue the narrative, then when the pictures end, the narrative in words picks up. My goal for Hugo was that at the end of the book you wouldn’t remember what was written and what was drawn. Wonderstruck is two completely different stories that parallel each other so my hope was that you would learn things about one story from the other story.

S&F: Did you work with deaf actors for WONDERSTRUCK?

BS: Yes. I learned so much about the Deaf community and the deaf experience while making the book, and tried to make sure the way that I portrayed the characters who were Deaf felt realistic to people who were themselves actually Deaf. Deaf people wear their language in a way that once you understand it, becomes visible. It’s a language where grammar includes what your eyebrows are doing and how you are positioning a character in space. If you are telling a story with three people, you indicate to people where they are standing. You just point to the space where that person is talking so it is a three dimensional language which is profoundly different than talking to someone with spoken language.

S&F: It sounds similar to directing.

BS: We cast six Deaf actors as hearing characters. Deaf actors were hired all the time for silent films because they were so expressive. Hearing children of Deaf adults were also hired a lot as actors because their first language was often sign language, so they would use their bodies in a more expressive fashion. Lon Chaney, the silent film actor, had parents who were both deaf. I thought it would be exciting to cast Deaf actors as hearing characters because that almost never happens. We have a 12-year-old Deaf girl named Millicent Simmonds from Utah who has never acted before as the lead, and she is extraordinary. We had sign language classes for the crew. There were scenes with three Deaf actors and five hearing actors and two interpreters and Todd making everything happen, and understanding that the Deaf actors need visual cues to know when to say their lines. For instance, when a hearing actor finished his line, he would put his hand on his hip, so when the Deaf actor saw the hand on the hip he would know to say his line. Some of the Deaf actors told me they had never been on a set with that kind of fluidity before. That was really wonderful to watch and be a part of. I hope you like it.

WONDERSTRUCK, adapted by Brian Selznick from his book of the same name, is directed by Todd Haynes, and will be in theaters in 2017. Museum of the Moving Image will screen HUGO in 3-D on December 24 and 30 as part of the Martin Scorsese exhibition in the galleries. Brian Selznick will introduce the screening on December 24. HUGO stars Ben Kingsley, Asa Butterfield, and Sacha Baron Cohen.

Brian Selznick is the author of six novels, and has illustrated over twenty books. He won the Caldecott Medal for the year’s best-illustrated book from the American Library Association for The Invention of Hugo Cabret. His new novel, The Marvels, is told in both text and images. The Marvels is now available where books are sold.