Wilbur and Orville Wright, brothers from Dayton, Ohio, were bicycle manufacturers who were convinced they could build a flying machine. They spent years notating the flights of different kinds of birds—the way the birds balanced, soared, and rotated their wings. The Wright Brothers invented the first airplane, and flew the first man with a movie camera.

The brothers conducted their first successful flights in the remote town of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Their bicycle shop’s mechanic, Charlie Taylor, built the first aircraft engine. Though the first powered flights took place in 1903, the United States government was slow to pay the Wrights any attention. So Wilbur, the eldest, went abroad to France where he broke world record after world record before the United States military took notice and invited the brothers to Washington.

The Wrights did not keep the secrets of flight to themselves—they added a second seat and Wilbur successfully trained pilots who completed solo runs, and subsequently trained military personnel. In April of 1909, Wilbur Wright was training military officers in Rome, and took aboard a news cameraman who shot the first-ever film from an airplane. A clip from this three-minute film, WILBUR WRIGHT AND HIS FLYING MACHINE, can be seen below:

Kevin Ferguson, in an essay “Aviation Cinema” published in Criticism in 2015, charts how the film, “begins with scenes of the airplane being prepared while observers wait expectantly. Next it shifts to a series of low-angle panoramic shots that track the airplane in the sky and are cut with a few spectacular shots as the airplane buzzes directly towards—and then over—the low-placed camera.” Though hard to discern from the grainy footage, a film still reveals the Roman aqueducts located in the distance.

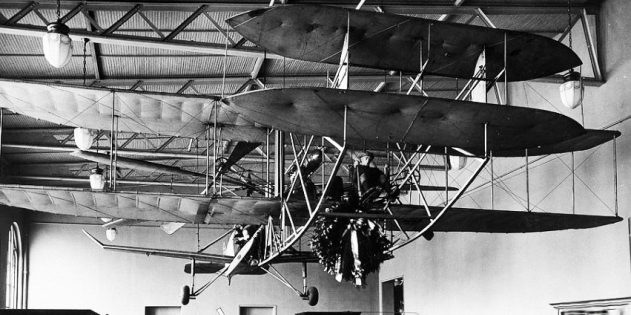

Seen through the cameraman’s lens, it is clear that the flight had a rough take-off but flew smoothly. The Wrights’ first flights were made using a derrick or catapult, which dropped a weight to launch the plane into the air. The plane did not have wheels, so once the weight was dropped it ran along a rail until the engine and propellers lifted it into the air. It landed via its skids, or runners. Ferguson makes the interesting point that, “the template this documentary footage sets—bumps and shakes and jolts, and then serenity—is reversed the moment filmmakers use flight as part of a narrative about modernity, speed, technology, or war. Afterwards, aviation cinema prefers to offer us a smooth takeoff but rough flying.” (p 310-11). The U.S. Military bought the Wright Flyer with which the brothers flew in 1909, and it became the world’s first military airplane.

In July of 1909 Orville Wright, the younger brother, took a U.S. Military lieutenant on a record-breaking flight in Fort Meyer, Virginia. A film of this flight is available below. At the start, the plane circles the field at about 25 feet, and then ascends as high as 150 feet. The Military purchased this 1909 model for $30,000.

People had been travelling by air in balloons for about a century when the Wrights began their work. A 17-minute film, THROUGH THE AIR TO CALLAIS, is about the French aeronautic inventor Jean-Pierre Blanchard who was the first man to cross the English Channel in a hydrogen balloon in 1785. The full film, by Joseph Mauceri, is available in the new Science & Film Teacher’s Guide along with discussion questions and resources for use in the classroom.

TOPICS