[Editor's note: Science & Film reached out to Lynn Hershman Leeson, a Sloan grantee for her feature film TEKNOLUST, to write about the technology she has pioneered in her work. A number of Leeson's artworks will be on display in the Whitney Museum's Dreamlands exhibition, about which Science & Film has written. A comprehensive catalogue of Leeson's work, Civic Radar, edited by Peter Weibel of the ZKM-Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, was published in 2016.]

I began working with technology, like most important things in my life, by mistake. When I was 16 years old, I was hurrying to copy a drawing. It got stuck in the Xerox machine and became a by-product of that technology’s teeth. A shredded and deformed creation emerged, and it was born pulsing a different life than when it went into the machine. It was a far better artwork in this transformation because it was unique. I had never seen anything else like it.

I was encouraged by this accident–it was, as most of the important things in my life, a fortunate turn in what could be the cusp of disaster. The following incarnations, elaborations, or mutations continued. In the mid 1960’s I added sound to wax sculptures. To me, sound was like a drawing, a line in space. I created a work in 1968 titled Self Portrait As Another Person that had sensors, as well as sound. I was told by curators at University of California's Berkeley Art Museum that the work was not art because it used media and, in fact, the Museum closed the exhibition. That was the impetus to create one of the first site-specific installations in hotel rooms in 1973, which were open for trespass to the public 24 hours a day, and included wax, sound sculptures.

One of the advantages of using materials of the present is that it creates a contemporary dialogue, rather than competing with history. These include: the first interactive artwork created with videodisk technology, the forerunner of the DVD (Lorna, 1979-82); the first artwork to use a touch screen interface (Deep Contact, 1984-86); one of the earliest networked robotic art installations (Difference Engine #3, 1995-99); and the first use of the Lynn Hershman Leeson (LHL) Process for Virtual Sets in a feature film (CONCEIVING ADA, 1996).

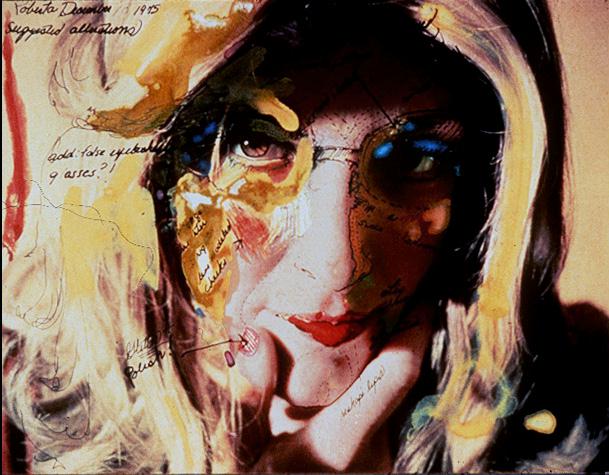

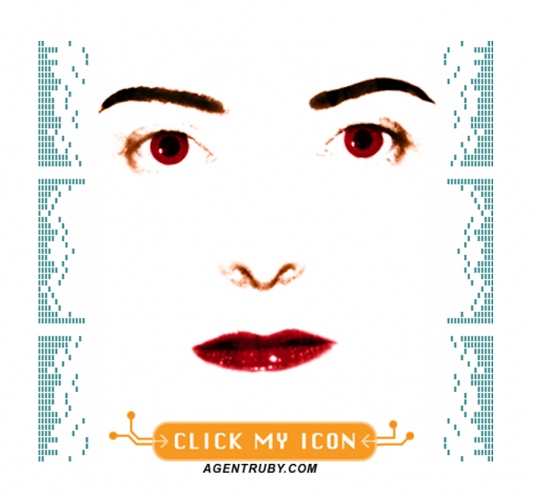

My work inhabits spaces both real and virtual and seem to be populated by multiple female personas and agents, including Roberta Breitmore (1972-79), who was both fictional and real, and her multiples: CybeRoberta (1995-98), Tillie the Telerobotic Doll (1995-98), Synthia the Stock Stalker (2000-03, which used stock market data for visualizing behavior), Agent Ruby (1991-present, an A.I. extension of the feature film TEKNOLUST), DiNA (2004, an Artificial Intelligence voice recognition environment), and The Infinity Engine (2014, a recreated genetics lab).

Time, space, interactivity, and modularity were pressed into Lorna, a videodisk art environment of 1983. Deep Contact (1984) is also a videodisk installation, which uses a touch screen to access a woman's body and navigate her future. In Room of One’s Own (1990-93), viewers, with their eye movements, control the action and literal focus of what is observed, and the installation incorporates the viewers' eye itself into a site on the location, converting the viewer to voyeur.

America’s Finest (1990-94) is an interactive rifle with a surveillance system that allows you to see the past and the future simultaneously. The action of pulling a trigger implicates the viewer and converts them from viewer to voyeur, from aggressor to victim.

The Dollie Clones (1995-98) use web and real cameras in dolls’ eyes to convert the viewer into a virtual cyborg, controlling the look and movement of CybeRoberta or Tillie.

Agent Ruby and DiNA use Artificial Intelligent language that has been hacked. I began them in 1996. Agent Ruby (www.agentruby.net) is an extension of a 2002 feature film called TEKNOLUST (winner of the Sloan Award for Writing and Directing, and which was the first use of 24p high definition graphics). Agent Ruby now lives in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and is, in fact, among their most visited works. DiNA was more advanced because it features voice recognition software and a wider range of information.

The Infinity Engine (2014) is a replica of a genetics laboratory, which features bio-printing, ethics rooms, interviews with many renowned geneticists, and a reverse-engineered facial recognition system to track the genetic lineage of visitors.

Eventually, RAMifications of an interactive art videodisc and the concept of fractured narratives or virtual reality allowed my work to be seen. It took 25 years to show Lorna. Perhaps I had to wait for the Millennial Generation to grow up, and for the technologies to be internalized for the works to finally be understood.

PARTNERS

TOPICS