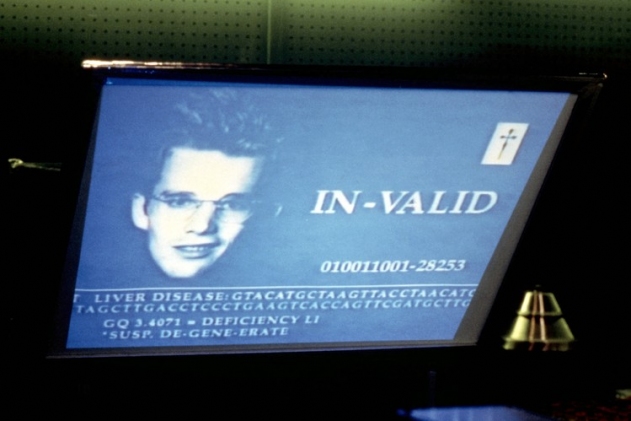

Andrew Niccol’s film GATTACA is more relevant in 2016 than it was when it was released in 1997. In the film, parents can choose the genes they want their children to have and children whose genes have not been modified are forever at a disadvantage. Before being hired for a job or choosing with whom to procreate it is normal to get the person’s genome sequenced. This society does not seem so far-fetched. We have the technology to sequence a genome for under $1,000 and edit it in humans using CRISPR. Science & Film spoke about the realities in GATTACA with cellular and molecular biologist Dr. Paul Durham from Missouri State University.

Science & Film: When did you first see GATTACA?

Paul Durham: This was a really fun film when it came out in 1997. It was on the cutting edge and I love the way they start the film with that phrase, in the not so distant future. That future is here.

S&F: Is the film more relevant today than it was at the time?

PD: Oh gosh, yeah. The thing that was crazy about it is we did not think we would get here as fast as we have. If someone would have said you could sequence a whole entire genome at the cost that we are doing it, which is under $1,000, and identify genes, we would have said [in the late 1990s], there is no way. We could not have projected that the technology could have advanced as fast as it has. So, it’s been a fun ride watching from where I was as a PhD student to see where it is today, where the technology is so accessible to everybody.

What this film is really getting at is, even though you may have a genetic predisposition toward something, it doesn’t guarantee you success, and it doesn’t guarantee you failure. For me, I give a lot of thought to the medical profession (neurologists, pain specialists) and I think the knowledge that we can influence the expression of our genes really empowers patients because it allows them to feel more in control. Think about how crazy it would be, like in the film, to know within seconds of your child’s birth how long they had to live. And yet, we’re kind of at that point. When I was at Iowa back in the 1990s we were told about a couple who had a son with cystic fibrosis. They thought it was a moral obligation to not only not have another child with cystic fibrosis, but they thought it was a moral obligation to not have it in their germline anymore. So, they went through in vitro fertilization since you can actually take a cell off the developing human embryo in those early stages, assay for the gene, and then the embryo will still be able to be implantable and develop perfectly fine. What this couple did was to choose an embryo that was not even going to be a carrier of the cystic fibrosis gene.

S&F: It’s like the scene in GATTACA when the parents are choosing from four different embryos.

PD: I pose these questions to my biology class: if you have the technology to know your offspring is going to have a genetic disease, do you have a moral obligation and a societal obligation to reduce costs long-term by just not allowing that child to be born? It’s a really tough issue. It cuts across political and religious lines. From a societal point of view, we spend the greatest amount of money dedicated to healthcare during the first and the last years of life.

S&F: The money issue raises the question of when, if ever, these tests are going to become mandatory? Will the health care system or insurance companies or government mandate that people get tested, and what are the implications of that?

PD: I ask my students all the time whether they would want to know their genome, and it really is about half and half. Back when I was getting my PhD at University of Iowa, I was a candidate as a bone marrow donor and had to go through a screening procedure. One of the things they found was that I had an alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency which codes for a protein that helps control the elasticity of your lungs. One of my genes is mutated so I don’t produce as much of it. So you would think that I have a predisposition towards emphysema and all types of lung problems. But here is the reality: if I would have been a smoker, I would, most likely, have developed emphysema. If I had lived in a really polluted environment, I would have emphysema right now. But the thing that was fortuitous for me is that I didn’t smoke, and I live in a really clean environment here in the Ozarks. So, I have never had any lung issues. When I was at Iowa they enrolled me in a study because they thought I was going to develop emphysema. It never happened. My point is, if I would have known that when I was ten years old, would I have lived my life differently? For me from a practical point of view, I think it is really powerful to understand your genetic makeup and your predispositions, because then your parents/doctors/teachers could help you make lifestyle choices to maximize your potential and minimize your risk of certain diseases. You’ve heard the term precision medicine right?

S&F: Yes.

PD: We can achieve precision medicine in that way. You have to understand what your predisposition is toward certain diseases, and then you would have the ability to implement changes in your life and environment to promote a healthier and happier self. Think about the cost savings from that type of approach to medicine and one’s life.

S&F: The film brings up a lot of bioethical issues, that being one of them. You are talking about genomic sequencing within a medical context, but in GATTACA it is determining your job, which I guess is your environment, but do you see that as being a reality one day?

PD: Being a professor, I see it everyday. I see kids with 34 ACTs, brilliant kids, who end up failing out of school. I see kids with a 20 on the ACT, they work their butts off, and they end up going to medical school. Intelligence is a funny thing. This is what I love about the movie, is that it talks about the human spirit. To me the most powerful message is at the very end, just saying live life to the fullest. Think about what [Vincent, played by Ethan Hawke] was saddled with—you’re only going to live 30 years, you only have this intelligence—and he starts out sweeping floors. I see it regularly at our school: the kids who really want to learn and are passionate about their future. If they are willing to put the time in, there is no reason they can’t achieve the same thing as another kid who is more gifted, so to speak, or who went to a “better, bigger” high school.

We are so fortunate in America since kids have the chance to choose their career path. I believe that our freedom to pursue our dreams is an amazing gift. In some countries, a person’s career option is decided by how well they perform on a single exam day. We have to remember that we all develop in our own unique way and we have to have the time to fully develop our mental, physical, and social skills. In China and Korea, they have a standardized test that determines your career path. Young kids have all that pressure on one day which really determines the direction of their life. This movie speaks volumes about that as well. I asked my developmental biology class, what are the traits you would want in your child, and the traits you would not want? I actually had one girl who said that if she had a red-haired child she would abort it. She thought that being a redhead was a serious, serious disadvantage in life. She would rather terminate the pregnancy than bring a redhead into the world. I was going, wow. It’s almost spooky. It’s scary when we start thinking about what specific traits or characteristics we want in our children. How do you explain selecting different traits for your different children?

This is not something in the future, this is happening today. Now that we have the ability to edit the genome with CRISPR, [Kathy Niakan] over in England [at the Francis Crick Institute] is doing it. She actually has gotten permission to edit the human genome, so she is doing that to human embryos. They’re only allowed to develop for a short period of time before they are sacrificed. A main goal of her research is to better understand early human developmental processes. However, there has been discussion of extending the time period in which they allow those embryos to develop.

S&F: Is there anything you are worried about with this gene technology, and where the field is headed?

PD: The biggest thing for me is what you hit on earlier. I believe it would be beneficial to build into our healthcare system the ability to sequence everyone’s genome since the information would allow clinicians to know an individual’s predisposition towards a particular disease. However, there is great concern about the security of that information. You hit the nail on the head when you said, what happens if a corporation or an insurance company gets knowledge of that? If you are found to have a predisposition towards a disease, would a company not be as likely to hire you or would you be denied insurance coverage for a “pre-existing” condition. That’s the danger. When I think about it long-term, it could be very detrimental if the information falls into the wrong domain.

I had a student come up to me after I was teaching about all this new technology and the genome. She asked, if I get my DNA sequenced and I get my sister’s DNA sequenced, do you think they’ll be able to sort out if we’re from the same father? She said, I think my mother may be trying to protect us from the truth since I don’t think we’re both from the same father. She went ahead and got her and her sister’s genomes sequenced and they discovered they are half sisters.

S&F: It reminds me of when I was in high school biology and we did this color-blind test, and all these guys discovered they were color-blind. It was very traumatic for them.

PD: It is a funny thing because I worked at Camp Courageous when I was younger, and disabled children don’t know they are disabled until you tell them they are. A lot of these things we subscribe to, like having a certain color hair or a high IQ, it doesn’t guarantee you happiness, and it doesn’t even guarantee you success. That’s what I love about the human spirit and the way GATTACA plays out. The man with the perfect genome sits in a chair and provides the samples and throws away his potential. You see athletes doing this every day in real life. You see these incredible athletes and they can’t keep it together and you say, do you know how many people would give everything to be in your shoes?

S&F: At the end of the movie the genetically inferior Ethan Hawke thanks Jude Law, who has the perfect genome, and Jude Law says in return, you gave me your dream. Have you ever read Andrew Solomon?

PD: What titles?

S&F: He has a degree in psychology and he writes about developmental challenges: he wrote Far From the Tree, which is organized into chapters about being deaf, transgender, disabled, and other groups that people identify with. When there is an option “to be cured,” so to speak, what are you giving up in terms of your identity? Being perfect isn’t everything.

PD: And how do you define perfect? There is no such thing as a perfect animal. Perfection means you’re not growing. In life, everything needs to evolve. We talk about macro and microevolution. Microevolution is a good thing. As the environment changes, something that’s an asset in one environment is not an asset in another.

It’s an interesting time with the abilities that we have now. CRISPR has changed everything. We knew we could change the genome, but we didn’t know we could do it this specifically. We can go in with a pair of micro-tweezers and take out what we don’t want. You can actually modify the DNA in ways not thought possible a few years ago. Kathy Niakan in England is using CRISPR from the point of view of better understanding early human development so that maybe we could intervene and prevent some of the developmental changes that cause long-term problems. For example, the technology could be used to remove the potential for hemophilia in the germline of the British royalty. Some would argue that it is our moral obligation to our offspring to not have this disease in the genome anymore.

The scientific community, unequivocally, said they are not going to publish this stuff. All the major journals (Science, Nature, Cell), said we are not at the place where we should be trying to do this kind of research. So, even though Niakan got permission to do it, there is not a lot of publishers or people who feel this is the way science should be going.

I look at myself, and I don’t have 20-20 vision. But, because I didn’t have as strong an eyesight, I developed other skill sets. People who are blind have other types of highly developed senses. People who had migraines in certain earlier human populations would have been considered to be gifted because they have a predisposition towards a very sensitive nervous system, and they sense the world very differently. Those individuals would be more sensitive to sounds and smells and changes in light patterns. Thinking about this from a biological view, they were the protectors in society since they would sense bad food and they would not sleep through a fire. However, they pay a price for this hyper-vigilance that protects the whole society. It is human nature for us to want to make things better including ourselves. With respect to our genes, you can say that people have a predisposition to something but it does not guarantee what the long-term outcome is going to be. There are many examples throughout history that demonstrate the powerful influence of the human spirit to overcome what appeared to be insurmountable odds.

Dr. Paul Durham is the Director of Cell Biology and the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences at Missouri State University, and a distinguished professor of cell biology. He is involved with organizations such as the Society for Neuroscience, the AAAS, the American Headache Society, and the Inflammation Research Association.

Dr. Durham introduced a screening of GATTACA at the Moxie Cinema in Springfield, Missouri, as part of its SCIENCE ON SCREEN program. SCIENCE ON SCREEN is a series pairing screenings of films with presentations by scientists. It was begun at the Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, Massachusetts and, with funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, has expanded to theatres nationwide. Science & Film has conducted other SCIENCE ON SCREEN interviews such as with a NASA engineer about OCTOBER SKY and a paleontologist about JURASSIC WORLD, among others.

PARTNERS

TOPICS