Dr. Stanley B. Burns lives in a multi-story townhouse in Manhattan with yellow walls and hundreds of thousands of photographs—from Nazi policemen who killed the first Jews during World War II, to the complete nervous system of a female patient, to the operating theatres of the early 20th century, to a surgeon reaching his hand into a patient’s chest, to a man with his skull cut open and brain exposed.

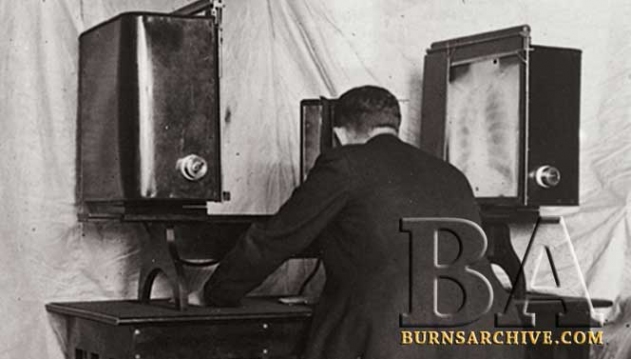

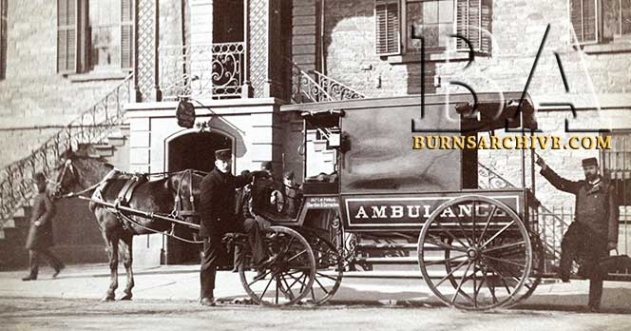

Dr. Burns has the largest private collection of medical photography and historic photographs in the world—over one million. It is all housed in his home, The Burns Archive, drawers open to reveal pocket-sized daguerreotype portraits framed in gold, and wall panels slide back exposing shelves of medical journals and photographic albums sorted by type and color. There are old vials of medicine, such as cocaine.

An ophthalmologist who first trained as a general surgeon, Dr. Burns took over the practice of a Nazi-era doctor who was the head doctor in the Berlin Police who came to New York, married a Jewish woman. When Jewish people came from Berlin to New York many became his patients. Dr. Burns is still a practicing doctor as well as Clinical Professor of Medicine and Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center. He has published 45 books, most recently the seven pound book Stiffs, Skulls & Skeletons: Medical Photography and Symbolism. He has consulted on hundreds of documentaries, and recently his archive has been brought to life in two television series: HBO-Cinemax’s THE KNICK and PBS’s MERCY STREET. He and his daughter, Elizabeth A. Burns, were on set–in New York and Richmond, Virginia–for both shoots. He served as the Medical, Historical, and Technical Advisor, and she as the Photographic Archivist and Associate Medical Consultant. Dr. Burns trained the actors in both shows in surgery and period medical attitudes. Just about all the surgeries recreated on THE KNICK Dr. Burns has performed at some time. MERCY STREET borrowed his collection of Civil War surgical instruments for use on set.

MERCY STREET, supported by the Sloan Foundation, has premiered its first season. Science & Film previously interviewed showrunner and writer David Zabel and executive producer David Zucker. THE KNICK has aired two seasons and is planned for four more. Created by Jack Amiel and Michael Begler, the series is directed by Steven Soderbergh and stars Clive Owen.

Science & Film visited Dr. Burns, his daughter Liz, and son J at The Burns Archive in the late afternoon on April 20. We talked with Dr. Burns about MERCY STREET, THE KNICK, and his collection.

Science & Film: What were the most important medical innovations during the Civil War, when MERCY STREET is set, and at the turn of the century when THE KNICK is set?

Stanley B. Burns: R.B. Bontecou was one of the only surgeons who took photographs during the war of wounded soldiers to show the results of treatment. He developed bone excision, which was to cut out a piece of the upper arm bone and simply sew the skin up. The problem was, you then had a useless arm, which was worse than no arm because it always got in your way. You couldn’t move it–you could flail it around. After the discovery of antiseptic principles in 1867 by Joseph Lister in England after the Civil War, most of these arms were cut off. Even then, very few doctors practiced antiseptic techniques, as was witnessed by killing of President James Garfield by doctors in 1881. Included in Stiffs, Skulls & Skeletons are pictures of his spine from his autopsy. The President was shot and the principle was the same Civil War bullet wound concept they were using 20 years earlier—stick your hands in the body to find the bullet. And that’s what they did: they made a huge wound with their dirty unwashed fingers. After Garfield died we finally went into antiseptic and asepsis surgical techniques. But during the Civil War you saw none of it, and doctors often held sutures in their mouths wetting it with saliva while sewing up.

On MERCY STREET we have a bone excision, which was done with a fancy saw to get around the bone.

During the Civil War, surgery was very serious work because of the large number of wounded. Doctors attempted as short a period of anesthesia as possible, so the surgery was quick—two minutes, five minutes maybe. It wasn’t a complicated procedure. Just quickly cut through the muscle and bone.

S&F: It sounds like you were teaching people how to do the wrong thing in the right way on MERCY STREET?

SB: It only was the wrong thing later. There is a lot of wrong medicine. I don’t know if you watch television, but they have lawyers on there everyday saying call your doctor if you ate spinach, or something like that. Call if your mother’s grandfather smoked near an asbestos plant. But you don’t know until afterwards the ill effects of chemicals, medicines, and procedures. But you have to do the procedures known at the time–come up with an idea to try to help and you only find out it’s wrong later.

S&F: That’s one of the things I love about THE KNICK—that it dramatizes that discovery process.

SB: You see every discovery, you see the thought process. What you’re witnessing there, a lot of the stories, are from my material. I have the complete library of the major medical journals from about 1885 to 1935. We have 10,000 books here.

S&F: Do people come here knowing exactly what they are looking for?

SB: Not extctly. People come here not knowing what they’re looking for, and then they find it. That’s why we were THE KNICK advisors, because I had written an article about a woman with nasal destruction from syphilis—this is one of the things I’ve been promoting for years because I have great pictures of that. All of that came out of here. When they came here they had a pilot, they left with a season. Where are you going to look for historic medical photographs? Here.

S&F: So the writers knew they wanted to write this show?

SB: Jack Amiel and Michael Begler, the writers, and Steven Soderbergh, the director, came here to discuss their pilot. They were supposed to be here for a half hour or so, and they stayed for several hours, and they got the stories because I showed them each and every one. That’s what I do; I’m a storyteller. I’ve written 1179 articles. From that day on I was a member of the team. Liz and I were on set for the entire production. Then we went through the procedures to show them what to do. We made sure the surgeries were period perfect.

We walked into MERCY STREET, into their big “idea” room, they had a room in this great gothic Moroccan building–the former Richmond City Hall–and it was just filled with photographs from my book Shooting Soldiers. So it was my photographs of wounded soldiers and operations that helped create the show. The nice part for me was that they listened to me when I made corrections and introduced some dramatic visual effects.

S&F: How was working on these shows different than consulting on a documentary?

SB: Usually a documentary is someone else’s story. These are my stories. The showrunners came to us with an idea and we filled in the blanks. The whole part of the brain that is filled with songs, for me is filled with pictures and stories. I don’t remember songs. Just think of all the songs you know, that’s all the pictures I have.

S&F: Can you give me an example of how you worked together with Soderbergh?

SB: The first day of shooting on THE KNICK they filled up the big surgery amphitheater with about 100 doctors, and Steven walks into the room and is getting ready to shoot and I said, this isn’t right. You have all these young, good-looking doctors up front. If Spielberg or Scorcese invited you to watch them film, would you be in the first row, or the last row? So it’s all the older experienced professors up front, and all the younger, inexperienced doctors who know nothing, who barely know what they’re seeing, in back. Steven listened–he then spent a half an hour rearranging the audience so that the older-looking doctors were right up front like they were meant to be. Had it been done the wrong way, all the historians in the world would have watched it and said, what’s Jake Gyllenhaal doing in the first row, and Sean Connery doing in the back row?

S&F: Have you ever had any historians critique the show?

SB: THE KNICK has only received positive feedback. I am a member of many surgical groups and all the historical groups. THE KNICK is perfect. One of the results of the series is the realistic and medically accurate medical models and prosthetics. Between Season 1 and Season 2 Fractured FX (the make-up FX company) was hired by Boston Children’s Hospital, a division of Mass General, to create prosthetic body parts so that surgeons could learn to operate. The neurosurgeons worked with [Fractured FX] to make sure that the skin and tissue and brain was exactly accurate. You couldn’t tell the difference between a real person and the prosthetic. That’s an example of how medical science was advanced from The KNICK.

What I say in every one of my lectures is that the doctors 100 years ago or 200 years ago were just as smart, just as innovative, just as interested in helping their patients, but they labored under inferior knowledge and technology. The one critical thing to come away from this is that 100 years from now they will look at us the same way. The way medicine is advancing, bacteria can be used as indicators of everything from asthma to diabetes. In 50 years they will be swabbing all your orifices and skin to see what’s growing on you and in you, and will be able to tell what you have and what you will get. Yesterday alone I was absolutely thrilled to see that they discovered how to diagnose pancreatic cancer through the growth of a certain bacteria. Martin J. Blaser, MD is Director of the Human Microbiome Program at NYU and was the major proponent of that theory. We were pleasantly surprised when Marty was one of the 100 most influential people in the world according to Time Magazine, because he has totally changed the concept of causation and diagnosis of disease.

Although I’m a practicing ophthalmologist, I am in both the departments of Medicine and Psychiatry at NYU, so I go to medical and psychiatric grand rounds, and it’s absolutely amazing. When I went to medical school they taught us that 50% of what we learned in five years would be outmoded. I’ve had so many five-year periods.

S&F: Did you have a good time working on the show?

SB: We had a great time because I saw my stories come to life and had the honor of working with such amazing people.

The first motto of The Burns Archive was “Preserving the Vision of American Medicine.” The Historical Collection includes sections on Death & Memorial, Judaica, War & Conflict, and more; the Medical Collection includes Anatomy & Education, Operative Scenes, Pioneers & Innovators, among others. A number of photographs from The Burns Archive are currently on display in the exhibition, “Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play,” up now through July 2016 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Photographs © Stanley B. Burns, Md & The Burns Archive

Cover photograph: Mary Cybulski/Cinemax

TOPICS