What is life? The Moderna Museet in Stockholm is presenting “Life Itself,” an exhibition that poses to artists a question scientists have tried for decades to answer. The show features science-themed films by two artists: Rachel Rose and Pierre Huyghe. The mandate of the show is “life Itself – on the question of what it essentially is; its materialities, its characteristics, considering that the attempts to answer this question by occidental sciences and philosophies have proven unsatisfactory.” The art exhibition curated by Jo Widoff, Carsten Höller, and Daniel Birnbaum, features artists from around the world whose work spans the early twentieth century through to the present day, including Rosemarie Trockel, Joseph Beuys, Eva Hesse, Philippe Parreno, and Trisha Donnelly.

Contemporary French artist Pierre Huyghe’s film UNTITLED: HUMAN MASK is a short which blurs the line between human and animal, and considers our distinctive nature. Hugyhe’s film is a response to a YouTube video which takes place at a restaurant in Japan employing a monkey. The monkey, dressed as a little girl, works as a waiter while wearing a human mask with a wig and costume to boot. She brings hot towels to customers and doles out high fives. Huyghe’s video uses the same macaque monkey. Jennifer Higgie in Frieze Magazine says of the piece,

“[I]n Huyghe’s work, conversely, the mask makes a mockery of the monkey’s innate characteristics: it’s the embodiment of anthropomorphism at its most seductive and cruel, creating a literal barrier between the monkey’s world and ours … His film is a stark and brilliant reminder that humans are the only species who regularly practice deceit – and that the only ones we are capable of deceiving are ourselves. You can put a monkey in a mask but, however hard you try, you can’t make it believe a lie. It knows it’s a monkey. If only humans were as wise.”

Could it be true that we humans are born only to grow bones, to die, and to deposit them back into the earth? Rachel Rose’s SITTING FEEDING SLEEPING asks directly—what is the point of life? Rose says of her work, “I shot SITTING FEEDING SLEEP in a cryogenics lab, where nitrogen-pumped bodies circulate their own blood. In a robotics perception lab, where machines read human emotion. And in zoos, where animals live extended lives emptied of sexual, social, survival cues. I used these three spaces as prosthetics for understanding deathfullness — being alive, feeling dead.” A Polar Bear yawns in an enclosure with too little snow, a yellow plastic oil canteen for him to play with thrown off to the side. Anthropogenic pollutants are clearly to blame. Images of a bioluminescent slug flash next to those of mashed up blueberries. She wonders if humans are merely a means to mutate materials. The entire video can be streamed online.

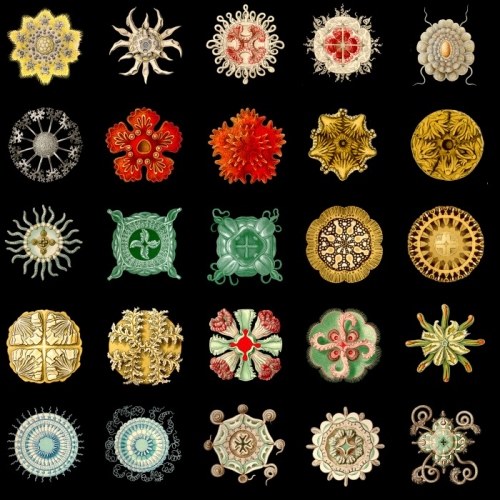

To accompany the exhibition “Life Itself,” an incredible catalogue of texts replete with biological illustrations by the nineteenth century naturalist Ernst Haeckel, who began as a scientist and became an artist, is being published. The anthology is 300 pages of 173 pieces of writing by synthetic biologists, authors, screenwriters, philosophers, chemists, mathematicians, historians, poets, philosophers, ethicists, and religious leaders on what constitutes life. Reading the breadth of writings is a life experience in and of itself. Some standout examples follow:

One way to consider life is to start with pre-DNA cellular life. Cosmologist Carl Sagan poses a definition of life as an object “exchanging some of its materials with its surroundings, but without altering its general principles.” Physicist Lawrence Krauss affirms that “’something’ can arise out of nothing without the need for any divine guidance.”

The book about life is as much about death. Jesus arose from the dead to walk amongst the living. Zombies are created when young people who have died are stolen by sorcerers and returned to life without full awareness or control of themselves, and without memory. The cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks live on. A study of cancer by Jackie Stacey in 1997 concludes that “cancer is ‘death infecting life’ by the means of life itself,” since cancer is a disease of cell reproduction. A character from Harmony Korine’s GUMMO says, “Life is beautiful. Really, it is. Full of beauty and illusions. Life is great. Without it, you’d be dead.”

Novelists wonder about the loneliness of being human. In Franz Kafka’s Blumfeld, an Elderly Bachelor, the old man’s lonely life is punctured by “two small white celluloid balls with blue stripes jumping up and down side by side,” and he realizes that it is “not quite pointless after all to live in secret as an unnoticed bachelor; now someone, no matter who, has penetrated this secret and sent him these two strange balls.” In Julio Cortazar’s Axolotl, the name for a Mexican salamander, the narrator remarks “the eyes of the axolotls spoke to me of the presence of a different life, of another way of seeing.”

An article in The American Biology Teacher in 2013 expands the definition of life to ask, “as we search for life on other worlds, how will we know when we have found it?” In ALIEN, directed by Ridley Scott, Parker wonders if the thing in front of him is alive—Lambert responds, “I don’t know, but don’t touch it.”

Aristotle claims that “it is self-nourishment, growth, and decay that we speak of as life.” Gilles Deleuze that “life is essentially determined in the act of avoiding obstacles, stating and solving a problem.” This myriad of responses supplements the artwork in the show, though the book can stand in its own right.

The catalogue will be available for purchase from the Moderna Museet’s online store. “Life Itself” opens February 20 at the Moderna Museet and is up through August 5, 2016.