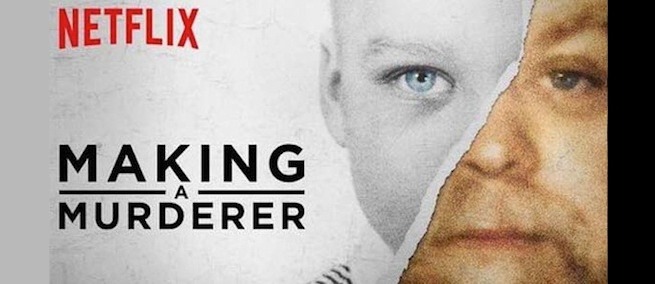

The newly released Netflix series MAKING A MURDERER centers on the convicted, exonerated, and then re-convicted Steven Avery. Over ten years ago, the Wisconsin Innocence Project used the innovative science of DNA testing to free Steven Avery, a Manitowoc County local, who had spent 18 years in jail for sexually assaulting a woman. Testing of pubic hair from the victim’s rape kit conclusively confirmed that another man by the name of Gregory Allen, who had been charged on a number of counts previously, was the perpetrator. Avery subsequently brought a lawsuit against the local sheriff’s office. But in 2005, after two years of freedom, Avery was convicted a second time for the murder of a young photographer. This time DNA analysis was used to his detriment, and Avery’s blood was identified in the victim’s car and on her car key. Episode one, which was released onto YouTube, centers on Avery’s first conviction, the trial, and his exoneration. In interviews with his family and defenders, it clearly frames Avery as the victim of a biased and corrupt justice system.

An article in The New York Times about Avery’s second conviction prompted two women filmmakers, Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, to begin this documentary, MAKING A MURDERER, which was ten years in the making and runs over ten hours. The series suggests that the police framed Avery for the second murder. From his first conviction there was a vial of blood in a sealed bag that was kept as evidence—the vial had clearly been tampered with, and blood extracted, at the time of his second conviction. The blood that was tampered with contained a preservative known as EDTA. In order to prove his innocence, defenders could test the blood that was found in the car for EDTA. This sounds simple enough, except scientific testing is not yet advanced enough to be able to do this. An article in the Washington Post quotes Avery’s post-conviction attorney saying, “What ultimately freed him was newly discovered evidence where the technology advanced to the stage where you could test the DNA…In this case, we’re looking for technology to do the same kind of thing, to show that the evidence at the original trial really did not mean what the state was arguing that it meant and what the jury believed that it meant.”

For more about the science of DNA evidence and how it can be used to overturn wrongful convictions, the Sloan Foundation supported the research, writing, and production of False Conviction: Innocence, Guilt & Science. Written by Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Jim Dwyer, this interactive ebook transports readers into science labs, interviews experts, and allows readers to dig into the technology that is helping to overturn many wrongful convictions.

Check back on Science & Film for an article by forensic DNA specialist Mechtild Prinz on the science in the series.