This weekend, Museum of the Moving Image will host a program of films seemingly tailor-made for readers of Sloan Science and Film. It’s called Computer Age: Early Computer Movies, 1952-1987, and it’s comprised of a few features which will be known to many (including Tron and The Last Starfighter) as well as a several programs of rarely screened experimental short films made with the use of computers. I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to check out a few hours of the material on offer and was inspired to conduct an interview with the program’s curators, Leo Goldsmith and Gregory Zinman.

Sloan Science and Film: Can you talk about the genesis of Computer Age? Your program introduction references some of the most famous recent digital films (Avatar, Toy Story), so I’m curious about how you see the older films you've programmed informing the current moment.

Gregory Zinman: We started by talking about the achievements in the digital effects in recent blockbusters such as Avatar and video games such as the Grand Theft Auto series. The emphasis on registers of verisimilitude, even with regard to the creation of imaginary landscapes and cities, got us thinking, "How did we get here?" We were wondering if the push towards the replication of reality in these works was an inherent quality of the digital, or rather a result of market forces and storytelling trends.

When we began to look back at the origins of computer films, we found strangeness—instead of images of reality, we saw wild abstractions, ones that marked differences between the real and perceived world, or that attempted to find correspondences between machine logic and subjective experience. We also found that early computer films featured some of the very first collaborations between artists and engineers—the kinds of partnerships that blossomed, for better and for worse, into the highly Fordian separation of labor we find in Hollywood special effects spectaculars and billion-dollar grossing video games.

We realized that our present, commercial, digital moment was shaped by radical experimentation and artistic endeavor, and we wanted to show just how diverse, bizarre, and enthralling its origins were.

SSF: So many of the films come bearing the insignia of technical laboratories (IBM/Bell) and the final inscription of “A Poemfield #2” is “A Study in Computer Graphics.” This connection led me to think about the interrelationship of science and art. Where did the filmmaker/programmers behind these works position themselves along that spectrum? Were they making films or carrying out experiments? When you see the folks in “The Incredible Machine” trying to teach a computer to read Hamlet’s soliloquy, you feel a certain kind of aspirational quality in the work.

Leo Goldsmith: I think there’s a pretty rich spectrum of intentions, from those who see their work primarily in an artistic tradition to those who saw it as a form of research. But most of these filmmakers are positioned somewhere in between—like Jim Blinn, whose work is divided between the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Industrial Light & Magic.

But this raises the very interesting larger question of what experimentation actually is—both in scientific experimentation and in experimental cinema. Of course, in both cinema and science, experimentation can be playful or searching, but in both instances there are also goals or anticipated results. And a great many experimental filmmakers—from Hollis Frampton to Jeanne Liotta—have engaged very deeply with science, mathematics, astronomy, and so forth.

GZ: I also think that there hasn’t been much attention paid to abstraction in moving images. As is the case with the vast majority of abstract painting, abstract films are very rarely mere formal exercises. Instead, they are often about new ways of seeing and new forms of sensory engagement with cinema and the world. In other words, abstract films almost always mean something. Part of what many of these early computer films were about were finding new ways to communicate beyond language, and with technology.

LG: Many of the works we’ll be screening—films by Mary Ellen Bute, Stan VanDerBeek, Ken Knowlton, and Ed Emshwiller—resulted from residencies with companies and institutions like NASA, IBM, NYIT, and Bell Labs, and this suggests a fascinating culture of collaboration, which the 1968 documentary The Incredible Machine represents quite well. The history of this culture is a ripe area for further scholarship. But of course it’s not just a question of how scientists and programmers influenced the way films are made, but also the opposite: how did the work of artists affect the design and functionality of interfaces the programmers were producing?

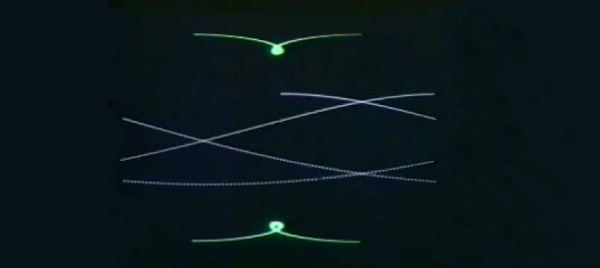

SSF: Is there a relationship traceable between these works and more “traditional” experimental filmmaking? Several of the films, like “Around Perception,” directly challenge the limits of what can be seen with the human eye, which brings to mind many different strands of avant-garde filmmaking.

GZ: Absolutely. The use of the computer by filmmakers such as John Whitney and Stan Vanderbeek relates directly to the graphic avant-garde films of the 1920s and 1930s—made by Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann, and Viking Eggeling. John and James Whitney had seen these works as part of the "Art in Cinema" series at the San Francisco Museum of Art in the late 1940s, and they knew Fischinger and other artisanal filmmakers, such as Harry Smith and Jordan Belson, personally. Ron Hays' work in the 1970s stems directly from a history of visual music—the efforts by artists to find perceptual and thematic correspondences between moving images and music, as seen in the work of Fischinger, Len Lye, and Norman McLaren. Like those artists, Hays made use of the available technological tools of the day, including Nam June Paik's video synthesizer and the Scanimate process. Similarly, the films of Mary Ellen Bute and Lillian Schwartz both represent extensions of Ruttmann's desire to use new technologies to paint in time, or to draw with electronics. And, as you point out, Hebert's "Around Perception" shares formal characteristics with the perceptual flicker films of Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits.

SSF: Early works in the series like “Permutations” and “Around Perception” are built around geometric abstractions, but as the technology progresses, you start seeing things like the smeared imagery of “Aquarelles.” Since this is a science-themed blog, could you tease out some of the technological changes in the period covered by your series and how they affected the work being produced?

LG: Certainly, texture-mapping—the practice of wrapping a flat, textural “shell” around a three-dimensional figure—was a crucial shift in these effects that’s quite visible here. Texture-mapping was developed in the early 1970s by Ed Catmull, later president of Pixar, so one can see how innovations like these led directly into the sort of computer animation we know today. In “Aquarelles,” Dean Winkler was using hardware and software he designed himself. One of the things we wanted to capture with the program was the degree to which these computer filmmaking processes were homespun, idiosyncratic, and innovative.

SSF: Can you discuss the early films’ fascination with Asian music and imagery?

GZ: The influence of Asian music and imagery in early computer films can be traced to a couple of intertwining concerns. Following the horrors of the second world war, many people, including artists, were searching for different belief systems and ways of thinking about humanity's place in the universe. This resulted, in part, in a flowering of interest in Eastern religions and philosophies, which in turn resulted in a number of cinematic works that simultaneously referenced other worlds and altered consciousnesses.

The Whitneys’ films are, in particular, are dedicated to representing complex mathematical patterns that occur throughout nature, philosophy and music. James Whitney's Lapis, for example,is an attempt to portray Pythagoras’s music of the spheres via tetractys, or pyramids of dots. Lapis refers to the alchemical philosopher’s stone of transformation, and Whitney himself thought of the film as a “space/time mandala”. Elsewhere, James described his art as being informed by “Jungian psychology, alchemy, yoga, Tao, quantum physics, Krishnamurti and consciousness expanding.”

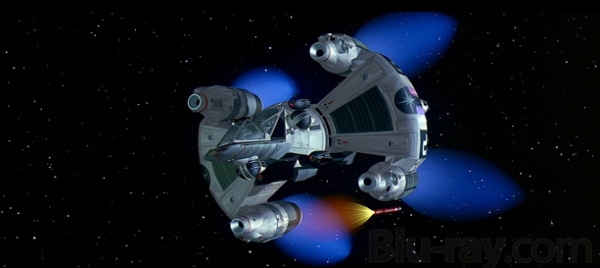

SSF: Along with the shorts programs, you’ve included a few more known features in the series--Last Starfighter, Tron, Demon Seed. How quickly did Hollywood move to take advantage of the potential of these new technologies? Was anyone thinking about how the incorporation of these new images would effectively “date” the films? 2001 looks like it could have been made minutes ago, but there’s a way in which relying on the best computer tech of the time instantly signals the era of production.

LG: Of course, it’s worth pointing out that John Whitney—whose work we feature on Saturday—originally offered to do all of the visual effects for 2001 with computers. And while Kubrick decided against it, Douglas Trumbull did adapt Whitney’s design for meticulously motion-controlled slit-scan for the Stargate sequence.

That being said, I think you’re right. Many of the first commercial films that used computers did so only to design specific images or isolated sequences—the credits for Vertigo (1958), for example, or particular images, sometimes just seen on monitors, in films like Future World (1976)or Looker (1981). It took some time for Hollywood to find ways of gracefully incorporating computer technologies into the cinematic toybox.

What makes films like Demon Seed, Tron, and The Last Starfighter interesting in this regard is not simply the fact that they devote more screen-time to these effects, but the way in which they actually try to work through the relationship between celluloid-based cinema and computers. Humans and robots, real-life and virtual spaces, cinema and gaming: these films were searching for ways to bridge media, both in their plots and how they were made.

SSF: Now that CGI is most commonly used to create images meant to convince us of their verisimilitude, is there still space for works like those you've programmed?

GZ: Computer-generated abstraction is more prevalent than people realize. Screen savers and iTunes visualizers are everyday, anodyne byproducts of the pioneering forerunners that we'll be screening. Contemporary glitch and datamoshing digital video artists like Takeshi Murata, Lauren Pelc-McArthur, Nick Briz, Peter Rahul, Adrienne Crossman, and Phil Stearns demonstrate the persistently radical possibilities—both aesthetic and political—of the digital.

LG: What’s interesting about many of these contemporary computer artists is that they’re often seeking forms of digital abstraction not by programming but by de-programming, in a way: hacking those now-familiar digital images to expose their underlying code or cause them to break down. Perhaps this suggests a shift in the way artists interact with those sorts of institutions or companies we discussed earlier, or perhaps it’s a result of our own evolving attitudes to the role that computers play in our lives. Often, computers seem at once ubiquitous and invisible, and I think one of the goals of contemporary artists is to make the digital more material and its origins more traceable. Which is of course what we’re trying to do with our program as well.

TOPICS