-min.jpg)

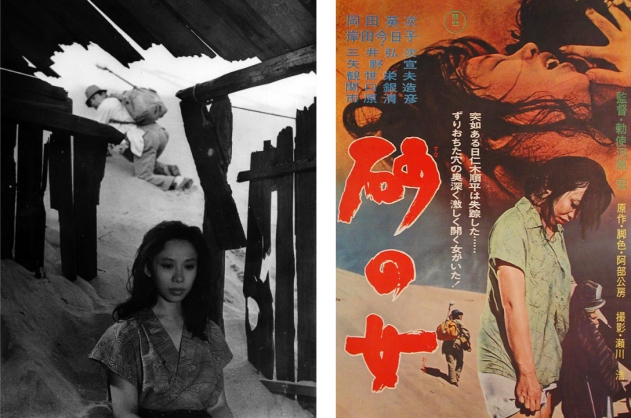

Hiroshi Teshighara’s landmark Japanese New Wave film WOMAN IN THE DUNES (1964) follows an entomologist as he travels to a beach outside Tokyo and ends up trapped by the townspeople at the bottom of a sand dune with a young widow. Prisoners, the two must constantly shovel sand to stave of both their own and the town’s annihilation. A collaboration between screenwriter Eiko Yoshida and surrealist writer Kōbō Abe, who authored a book of the same name in 1962, WOMAN IN THE DUNES is an allegorical story that can be interpreted in a multiplicity of ways.

For Science on Screen: Extinction and Otherwise, which examines socioeconomic, political, and ecological structures that have contributed to our unstable times, we spoke with celebrated author and economist Sonali Deraniyagala, whose work focuses on the economic impacts of natural disasters worldwide, with a specific focus on South and East Asia. She teaches in the Department of Economics at SOAS, University of London as well as at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Her 2013 memoir Wave recounts her experience during the Indian Ocean Tsunami when she lost her two sons, her husband, and her parents, and the progression of her grief in the ensuing years. It was shortlisted for the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award and won the PEN/Ackerley Prize, among many other honors.

WOMAN IN THE DUNES will screen in 35mm at Museum of the Moving Image on Sunday, February 13.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Sonia Epstein: What defines a disaster in your line of research?

Sonali Deraniyagala: Disasters that I research are geological or climate-related, meteorological. We could call them natural disasters, though there is a lot of debate about that word “natural.” If it happens in the middle of a desert where no one is living, then it’s not a natural disaster. It only becomes a natural disaster when society is involved. COVID is a biological disaster. Something like Chernobyl is chemical. In Japan you had a natural disaster in 2011 which was the tsunami and earthquake, and then the nuclear disaster which was not “natural” in that way. A disaster is many things, but in my research it is geological and meteorological.

SE: What natural disaster maps most closely onto what we see in WOMAN IN THE DUNES?

SD: When Nepal had a big earthquake in 2015, because Nepal is so mountainous there were huge landslides up in the mountains and villages were buried which look like the film—sand coming down permanently. In South America there are landslides which have buried entire towns or villages.

-min.jpg)

Still from WOMAN IN THE DUNES. Courtesy of Janus Films.

SE: In WOMAN IN THE DUNES, the people who are trapped are literally at the bottom of society, digging out for their own sake and for the sake of the village. Can you relate that to the populations you study in terms of those who are most affected by disasters?

SD: Typically, globally, poverty and disasters are connected. Those who are socioeconomically deprived are much more vulnerable to all types of disasters. In Mumbai, for example, there are urban floods, and it is the very poor who live in the areas that are prone to flooding. This is because there is pressure on the land, so all the good land is taken—it’s more expensive—so that pushes people [to areas susceptible to flooding]. In Vietnam, along the Mekong, it is the poor who are very exposed. To drought in Africa, it would be the same story. In Myanmar in 2008, there was Cyclone Nargis and 150,000 people died, people who were living in makeshift housing on stilts in salty marshes. The vulnerability of the poor to disasters is extremely high. When I say the word “poor,” the poor can be technically poor as in below the poverty line, or less well-off [than others].

You could think of the sand falling on your head all of the time [like in WOMAN IN THE DUNES] as a kind of recurring disaster. Living somewhere that is very exposed to landslides, floods, or even drought, every year you have got to cope. In Bangladesh there are people who are called Char Dwellers who live on riverine slips of land—the bits of land that appear and go away with the floods—who are permanently trying to raise up their rice beds. It’s a bit like that in the film—you’re fighting all the time, it never stops. In Japan at the time [WOMAN IN THE DUNES was made], there were these village communities who were considered lower caste. For the film to be set there I thought was relevant to the study of disasters.

SE: Is it just that the poor are more vulnerable and the wealthy are less so, or are there other ways the poor are affected?

SD: The poor are a) more vulnerable and b) they lose proportionately more. Your house is on a riverbed that is going to flood, and when it floods you lose all your assets, or all your wealth. As a proportion of your total wealth, you lose more if you are poor. The wealthy, even if they lose a house, it could be only part of their total asset portfolio. Watching WOMAN IN THE DUNES I was thinking about when she eats, and the sand falls and she has to cover her food. She has to protect the few things she has because if she loses her food, she is not going to get any more until they drop more food down. It is an extreme analogy.

It is a very unusual way to read WOMAN IN THE DUNES in terms of disasters, because the film is so existential. The usual discussion around the film is of the hopelessness and struggle, but this is a different take.

SE: WOMAN IN THE DUNES seems so multi-layered to me. What else stood out to you about the film?

SD: It was a woman, a widow who was sacrificed. It is all about powerlessness in society, isn’t it? There is one study that has been done in eastern regions of Tanzania about when elderly woman are labeled as witches and murdered. Over five years in the early 2000s, somebody observed an increased number of witch killings which happened by members of their own family. Then, a group of sociologists did some research to see if there was something underlying this or if it was just ideology or superstition, and what they found was that the murders correlated with periods of extreme weather: either too much rain, or drought. When there was extreme weather, there was a scarcity of food. This scarcity of food within the household resulted in people turning against granny—calling their relative a witch and killing her. In WOMAN IN THE DUNES, the vulnerability of this woman within the village was a little bit similar. The fact that she was a woman and a widow increased her vulnerability. The village treated her with such carelessness.

Left: Still from WOMAN IN THE DUNES, courtesy of Janus Films. Right: 1964 Japanese poster for the film.

SE: There is a line from the film: “Are you shoveling to survive, or surviving to shovel?” I wonder what you think of it. To me it brings up the question of resilience which I know is a loaded word within the disaster field. But it makes me think about the quality of life these people have under extreme conditions.

SD: That is a very profound line. Looking through a narrow disaster prism, you would say they are shoveling to survive. If you are very vulnerable and exposed because of climate change and more desertification or increased flooding, you are shoring up your defenses all the time. Resilience is very big in the disaster literature and I kind of avoid it because, what does it really mean? It makes me uncomfortable when people talk about the resilience of the poor. They shouldn’t have to be resilient; they should have the resources rather than us admiring them for having survived with little! They need interventions that make the need for resilience less. You need big disaster or risk reeducation programs: shelters for cyclones, or cash payments when something strikes rather than making people apply for loans to repair their house, it should be direct cash transfers given to people, so they don’t have to shovel to survive.

In economics we talk about a model called the “Poverty Trap Model.” You have two households, and one is a bit better off than the other. Their incomes are rising slowly over time and then a disaster strikes. There is a minimum of assets that they need in order to improve over time; it could be, say, a fishing family and they need a fishing boat and net. As long as they have that they can send their kids to school, have good nutrition, the children’s cognitive skills improve over time, all of that. But say there is a flood, and they both lose the fishing boat and net, the poor family might never be able to get one again. The better-off family can replace it or can get a loan to do so. The poor family isn’t credit worthy, they can’t get a loan, so they are always going to be struggling below the poverty line. That poor family never comes above that minimum threshold, so all the time they will be shoveling to survive and surviving to shovel.

SE: Can you speak a bit more about the kinds of interventions that you think would make a difference in disaster recovery?

SD: It depends on the type of disaster and who loses what. The key would be to intervene where it matters, and to really identify those who have lost the most and try to address that. Even the best-intentioned programs often can fail. One example is in the U.S. after Hurricane Katrina. The Road Home program was FEMA enabling people to rebuild their homes in New Orleans, especially in areas like the Lower Ninth Ward that really flooded. What research has shown is that the wealthier households, generally white, were better off after the Road Home program and the Black households were worse off. So, the Road Home program actually made Black and white inequality worse in parts of New Orleans. Why? Because Black families are more likely to be renters, and people who rented were not given the same kind of support that homeowners were given. Or, people in the Lower Ninth who owned their homes sometimes did not have access to their deeds, or those homes were valued at much lower than the equivalent in a wealthier, white area. That is the result of a historical process of segregation that resulted in an almost deliberate devaluing of Black neighborhoods. What disaster relief did there was increase inequality—a completely counterintuitive result.

There are some very good statistical studies done by a sociologist at Rice University in Houston where they show over a period of maybe 20 years, county-level data in the U.S. where FEMA aid has been given. A county that got FEMA aid would be a county where there has been a disaster, usually a hurricane or flood. They found that in counties that got FEMA aid over a 20-year period, white families were $55,000 better-off than white families that did not get FEMA aid. Black families, in counties that got FEMA aid, were $55,000 worse off than Black households who did not get FEMA aid! So basically, aid has increased inequality, purely because aid insurance or FEMA aid is given based on the value of your property. The more valuable the more you are going to get, and if you are renting or have a house of low value, you get less.

SE: So are you suggesting more on-the-ground intel about who actually needs aid in times of disaster?

SD: It doesn’t even have to be that on the ground to realize that people who are renting are worse off, so make sure that you have some aid for people who have to pay their rent. In a way, it is like helping that village in the movie but not helping that woman.

SE: What about the mindset of people who live with such recurrent disasters?

SD: In the context of WOMAN IN THE DUNES we’re talking about people living in close proximity to disaster. Most people [in that situation] would struggle economically and so on, but live fairly normal lives. You’re not thinking about the disaster all the time; it is imminent but something you just kind of respond to. It’s not [a life] without hope! People have the same aspirations—they want their kids to be educated and move up the ladder, to have lots of fun, there are communities, it’s almost not about resilience. People organize in fairly normal ways even in precarious situations. We have got to stop the precariousness but it’s not like people are entirely bogged down by it. I don’t mean to belittle in any way the situation, but, they have other concerns as well: fighting with their neighbor, they can’t stand their mother in law, it’s all going on. Hope is if we can reduce vulnerability.

SE: Is there anything that you would suggest people do or learn more about in terms of protecting vulnerable populations?

SD: Everyone is aware now about climate change. Individual climate actions do matter, but it is really pushing for change at the governmental level. To understand the history is important. Even Hurricane Katrina, it was something in the making over hundreds of years; when you go dredge the marshes for oil, and build a canal, and make people vulnerable… it happens over a long period of time. A lot of disasters are historical, and I think that again we can relate that to the movie. That village, why is it there? Why are they hustling by selling crappy sand to builders to make buildings that will fall in an earthquake? Especially being Japan, such a seismically active country. One of the best things we can do is try and understand.

We need to understand that natural disasters are actually not natural. Earthquakes are natural in that you can’t do anything about them, but you can move people away from those areas. We respond in terms of charity when it happens, but we shouldn’t dismiss such a disaster saying there is nothing we can do about it and it’s a natural disaster. It’s not. The 2011 earthquake in Haiti, Port-au-Prince is on the biggest fault line. Due to historical reasons of trade policy and lots of things, all these urban poor congregated there living in bad housing looking for jobs.

One little thing I thought of related to WOMAN IN THE DUNES was about loss. [The widow] says that she’ll leave when she finds her son and daughter and husband. A friend of mine who is an anthropologist did work in Sri Lanka after the tsunami and she always talks about a case of a man who lost his wife and children in the tsunami on the east coast of Sri Lanka. At that time, there were interventions and people were given new housing. His house was destroyed, and he was given a new house, but he wouldn’t go into it. He was a fisherman and only the cement floor of his former house remained on the beach. He sat there all day and night because there was an imprint of his daughter’s foot in the cement from when she was a toddler and they had poured it. Just like in the film when the widow says she will only go when she has dug out her family, I can remember that he wouldn’t move even though he had a new house. He sat there, had no roof, but he was there watching over that imprint. You can give all the interventions in the world, but people are emotional beings and economics are only a tiny part of it.

♦

TOPICS