In 1961, anthropological filmmaker Robert Gardner led a Harvard Peabody expedition to Netherlands New Guinea (current day West Papua) to shoot his landmark documentary DEAD BIRDS (1964). The expedition, designed to study the Hubula people of the region, was funded in part by the Rockefeller family and was supported by the Dutch colonial government. It took place two years before Indonesia took over the territory, which indigenous Papuan people continue to protest to this day. Sound artist Ernst Karel was called upon to revisit outtakes from DEAD BIRDS by Gardner’s family after his passing in 2014, and in the process came upon 37 hours of digitized sound recordings taken by a 23-year-old Michael Rockefeller, who was on the expedition and disappeared in Papua three months after the expedition ended. Karel, together with anthropologist Veronika Kusumaryati, has composed a new work based on these recordings called EXPEDITION CONTENT, which made its world premiere at the 2020 Berlin International Film Festival in the Forum Expanded section.

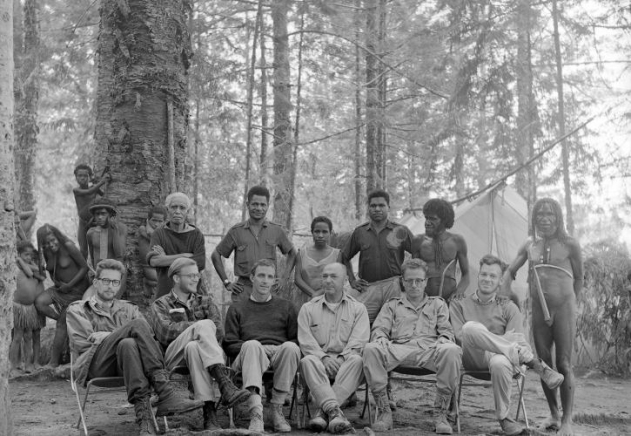

The experience of watching EXPEDITION CONTENT is more akin to hearing a story than watching a film; most of work unfolds as a sound piece, so one’s mind creates scenes based on what is being said, rather than there being any corresponding image on the black screen. The only extended scene in the film is from an outtake of DEAD BIRDS. Otherwise, the screen occasionally flashes blue and translations of some of the dialogue appear. The sound was recorded by Michael Rockefeller, who some of the Hubula call “Mike,” and is of the interactions between he and other members of the expedition team with the Hubula—which included author Peter Matthiessen, anthropologists Karl Heider and Jan Broekhuijse, and photographer Eliot Elisofon.

Harvard-Peabody New Guinea Expedition, 1961. From L-R: Karl Heider, Michael Rockefeller, Peter Matthiessen, Eliot Elisofon, Jan Broekhuijse, Rober Gardner, and Wali. Photo by Eliot Elisofon.

After EXPEDITION CONTENT’S world premiere at the Berlinale, we stayed for a conversation between Veronika Kusumaryati, Ernst Karel, and filmmaker Philip Scheffner, moderated by curator Nicole Wolf. An edited and condensed version of that discussion is below:

Nicole Wolf: How did you start approaching this material?

Veronika Kusumaryati: We started to work on this material in 2015, when Ernst was called to work on the outtakes of Dead Birds, the [Robert Gardner] film. Ernst showed me this work, and I had been working in West Papua, so I was instantly attracted to this. Because Michael disappeared in West Papua, we didn’t know until a few years ago about the fate of these tapes—the family donated the tapes to the Harvard Peabody Museum, the anthropological museum at Harvard, and they sent the tapes to be digitized at the at the Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music. So we worked with digital archives.

Ernst Karel: There were short films that Robert Gardner had been working on with various assistants over the years that he wanted to make from unused material from DEAD BIRDS. These short films have now been finished, but not yet released. Incidentally, we also have all of these audio archives and are exploring them; it was kind of mind-blowing to discover that all of these archives existed and had been digitized. We’re always very conscious of that particular lens of the microphone, which is in Michael’s unsteady hand—with handling noise and wind noise and people nearby, and his frustration, and all of these other aspects. It’s almost never a transparent window into another world, as we sometimes want to think audio recording can be. It’s always itself in some way, it’s always its own materiality.

VK: Michael had just started to learn sound recording in December 1960, so it was a few months before he went to West Papua. This is material that I think you said is colonial [to Nicole]? Yes, it is a colonial enterprise, but the uniqueness of this archive is also the context in which it was recorded. This is part of the Harvard Peabody Expedition to New Guinea, which took place during the transition from the Dutch colonial rule to the Indonesian one. The U.S. played a very strong role in the transition between the Dutch to Indonesia rule. The second context is also important which is that this is the last phase in the field of social anthropology where you sent a group of scientists, photographers, and filmmakers to document one single community. At Harvard, there’s an extensive and overwhelming archive that’s available of sound, film, visuals, photographs, and paper archives. In light of the disappearance of Michael Rockefeller and the situation in West Papua today, this is an archive that really calls for artists or filmmakers or anthropologists to work on.

NW: The expedition material that you are talking about is material that anthropologists built a career on, basically. So what you are now doing is, how I read it, to look at something else in the material. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the choices that you made in what you picked from that material, and how you are leading the viewer/listener through the material?

Ernst: The piece evolved; it wasn’t clear from the beginning that it was going to be focused as much as it is on the expedition members themselves. There were various possibilities in the material, from focusing on music, singing, or on performances. But it became clear that we were interested more in the aspects of, we could call it “everyday life” that Michael was recording.

The camera was a loud camera. You hear it a few times, especially early in the piece, this brrrrr of the 16mm camera, so it was impossible for them to record like people do today with sync sound—camera and microphone next to each other. So Michael had to take this attitude which is a little bit reminiscent for me of that of the contemporary field recordist who moves around looking for interesting things to record. He had different categories that he used that we hear in the piece: occupational sounds, sounds of nature... It seems that the main reason that he was recording sounds was to record things that would be useful for the film [DEAD BIRDS] but it went much more broadly than that. He was quite exploratory in the recording so that presented a number of possibilities.

Veronika: There was a lot of conversation about whether it’s about the Hubula, whether it’s about the expedition, whether it’s about the encounters between them… At the end of the day, of course it’s a technical choice, but it’s a political choice [too], particularly in light of this expedition. Maybe it is also in conversation with anthropology and in social science and humanities, the question of can the subaltern speak? [Note: This is the title of a 1983 essay by Gayatari Spivak, in which the term subaltern refers to colonialized, marginalized groups.] They do speak. But do we listen?

We also wondered how the Hubula considered the expedition team and the arrival of these white guys. There are some conversations in the tapes about these white guys. Ethnography is always about this. We are trying not to represent just the colonial gaze, but to look at Michael Rockefeller and Robert Gardner as ethnographic subjects too. They come from a unique social milieu that’s very different from the Hubula.

We have also been in conversation about the colonial gaze, and how we understand that in relation to this kind of archive, which is challenging to the notion of the colonial gaze that the film DEAD BIRDS actually created. We are very much in conversation with the film, and how the film framed the Hubula in such a way. For instance, the film focused on the warfare, and the focus on bodies, and the focus on male bodies in particular. We listened to a lot of tape in which Michael talked with women—this is something that is not visible in the film, but is audible in the tapes.

Philip Scheffner: For me, when I was watching the film I was triggered by how you decided where to put subtitles and where not to. I would just be interested to hear more about that decision because in the beginning, frankly, I was really irritated, because I thought like why the fuck am I not allowed to understand what people are saying? Because I think it’s not only the question of who’s the main, let’s say, subject of ethnographic filmmaking research—you said as I understood it that Michael is the main object of research—but also it’s the question of who’s the protagonist?

EK: This was a sound piece only for a long time. We didn’t conceive of it at first to have any image component.

VK: So it was a late decision to put text in. I think all the songs are translated, the Hubula songs from West Papua. We also decided to put the minstrel song that Michael sang. Why? I think because the song is very interesting, it’s history, it is a song that white Americans performed of African American slaves. We wanted the audience to understand the racial tone of the song.

EK: We also made the choice not to subtitle, so there were moments when we did subtitle, but those moments were already in the piece when we were conceiving of it as sound only. Late in the game, actually, we were looking over notes and reviewing what Veronika got from listening to these tapes with people in West Papua. We felt that it adds another dimension to subtitle. It seemed important to us, even as we decided to do that, to not then create an expectation that everything that was going to be heard was going to be treated as language. We wanted to still preserve the experience we’d had listening to these materials about place, about tone, about relationship between foreground and background, without always reducing language to its semantic content. So, even while we satisfied that desire here and there in the piece, we didn’t want to create an expectation that that would be what the piece was doing throughout.

PS: My problem is that I understand every single word that Michael is saying, but I don’t understand the other parts. So it’s like for me as a viewer, I’m directly being placed, located, so it’s not that I can listen to it just as a sound, as if I would look around in a nontoxic area… no, it’s very clear: I’m with that white guy standing there and I’m looking at something that I don’t understand, so my perspective has been fixed and I can’t escape it until the subtitles come, and then suddenly I realize that maybe there is another dimension.

VK: We don’t want also to give an illusion that we are there and are immersed in the environment without any mediation. This guy is the mediation, Michael Rockefeller is the mediation, the microphone is the mediation, and there is no such thing as a transparent reality that we can access. There has been a lot of conversation about sound as a way of knowing—the visuality or ocularcentrism as a foundation of epistemology of Western knowledge. There are a lot of critics of sound as a way of knowing, what kind of knowledge is this? It’s so partial, we cannot understand the content well, there is no context, so any knowledge is partial.

EXPEDITION CONTENT is directed and edited by Ernst Karel and Veronika Kusumaryati, and produced by the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University. Karel is known for his sonic ethnography work on films such as SWEETGRASS (2009), LEVIATHAN (2012), and THE HOTTEST AUGUST (2019). Kusumaryati is a political and media anthropologist working in West Papua, and a Harvard College Fellow in Anthropology, where she is also part of the Sensory Ethnography Lab. She has worked as a curator and producer of documentaries.

TOPICS